An Introduction

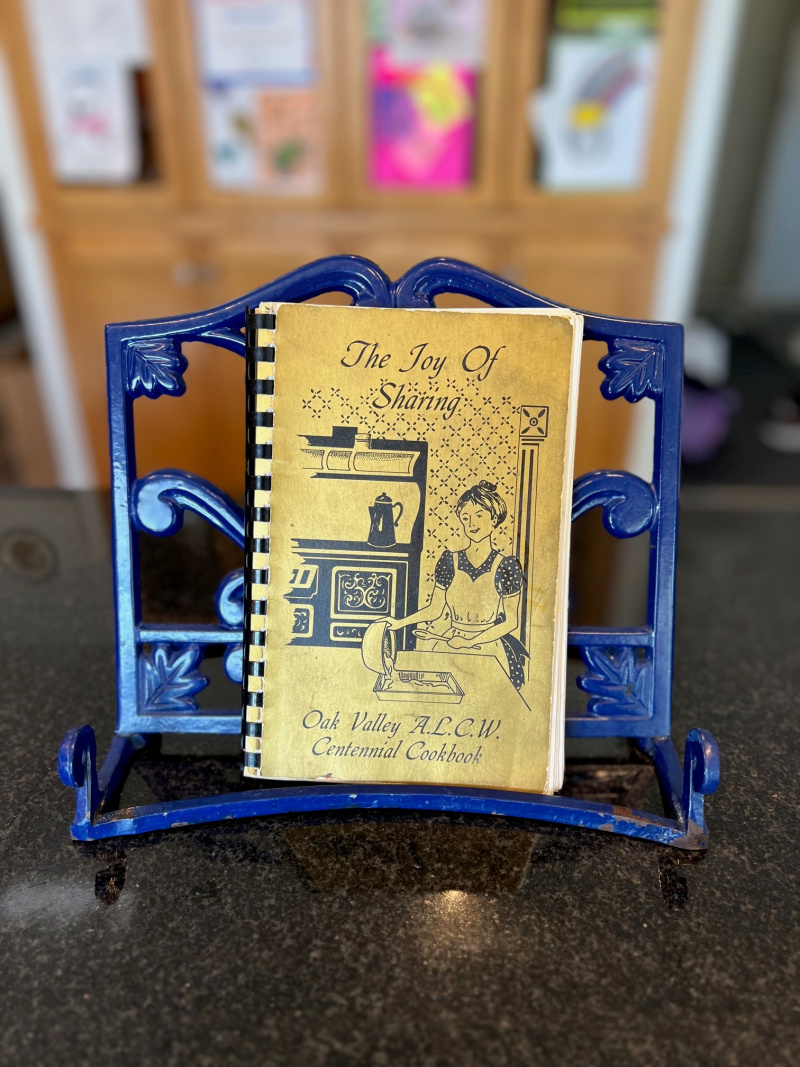

During summer 2023, I am cooking my way through The Joy of Sharing: Oak Valley A.L.C.W. Centennial Cookbook, published in 1985 by the Oak Valley American Lutheran Church Women in Velva, North Dakota. Now a congregation of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America or the ELCA, Oak Valley Lutheran Church is the church I attended during my childhood in central North Dakota.

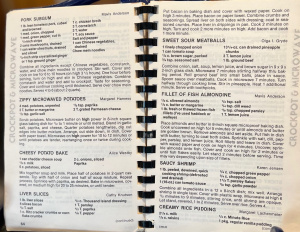

The Joy of Sharing, like other cookbooks published by communities, families, and organizations, reflects the conventions of its genre and period; it provides a brief history of the women’s group who composed it, pearls of wisdom and spiritual guidance, recipes attributed to the contributors, and categories of recipes indicative of the community’s identity, such as an “ethnic” section devoted to Norwegian and German foods, and a section for dishes made in the microwave.

The Plan

I will make three recipes each week and feature each recipe in a blog post. The posts will discuss the ingredients, the techniques involved, the type of food and its intended audience and purpose, as well as what I know and can discover about the contributor and their life and family.

I will employ a variety of approaches to making the recipes, including strict adherence to the instructions, making the dish more than once but with changes such as reduction of cooking time or the use of a probe thermometer, and making the dish with adjustments I propose, such as substituting an ingredient I prefer (like butter rather than margarine) or using what I have on hand (like the already thawed vension steak in my fridge, rather than the round steak prescribed in the recipe for He-Man Casserole). As I know from growing up on a farm fifteen miles from the nearest grocery store, cooking often involves creativity when ingredients are missing or disappear more quickly than expected. Many of contributors to The Joy of Sharing would have employed substitutions if necessary.

During summer 2023, my selection of recipes will be whimsical, based upon what sounds good, what sounds fascinating and surprising (sausage cake!?!), what food-related needs I have at the moment (weeknight dinner, various parties and gatherings, kids’ playdates, and so on), and what I anticipate my family will eat. While I do not intend to do any canning (I’ve read Jane Smiley’s A Thousand Acres. Canning is dangerous!), I will prepare recipes from every other category (and I can make the “to freeze corn” recipe from the jelly and preserving chapter).

My commentaries will reflect on contemporary techniques, ingredients, and uses that I might expect in a cookbook published today, as well as on my use of the dish and evaluations from those eating with me.

Much of what I learn about individuals in this initial research will be gathered on the internet, as well as from another book published in 1985, McHenry County: Its History and Its People. Published to celebrate the centennial of McHenry County, ND, this remarkable text is a compilation of more than 2000 family histories solicited by the McHenry County Board of Commissioners and chairmen for each county township and compiled by the General Chairmen, first Cleo Cantlon and then Corabelle Brown. Brown notes in her preface that these family histories were submitted and remain mostly unedited, “to preserve to flavor of each author’s style” (3). Thus, I assume that most material regarding residents of McHenry County is accurate and published with permission.

In addition to the family histories, the book includes photos, maps, and historical articles researched and written by various contributors, describing the area’s geology, the immigrant groups who settled in the region following the Homestead Acts in the nineteenth century, as well as the establishment of the various towns extant and no longer extant, school districts, and government entities.

Most notably, the book opens with an essay by Eric Sevareid, Velva, ND’s most famous and storied citizen. Noting that he was born in Velva in 1912 and lived across the street from Oak Valley Lutheran Church, Sevareid reflects upon continuous change and how different the region seems to him in 1985:

When I close my eyes and try to remember our life back then I see those artifacts of the Victorian age. I can barely visualize air bases and emplacements for nuclear tipped missles [sic] that could soar out of holes in those pasture lands and annihilate thousands of strangers in distant lands. I confess I don’t like to think of this. I am sorry it has happened, though I am aware one cannot cling to nostalgic sentimentalities forever. Life goes on, for better or worse; we are all bits and pieces in the wheel of history and we can’t escape it. (2)

Though many people who contributed to McHenry County and The Joy of Sharing have passed, some of the contributors to this cookbook are still alive. I hope to interview as many as possible regarding the recipe they submitted and their relationship to it—how it came about, when they served it, how often they made it and in what context, as well as whether it is still in their repertoire of meals.

The Inspiration

I love scalloped corn, or any type of gooey corn casserole, really, and I usually make some version of it for holiday meals (depending on what we serve, of course). Recently, as I reached for my copy of The Joy Sharing, which originally belonged to my paternal grandmother, Martha Knutson, to prepare Cora Michaelson’s scalloped corn recipe, I spent some time flipping around to see what else looked promising. I certainly was surprised at what I discovered.

This project was inspired by finding the recipe for liver slices, housed in the microwave section. The recipe calls for covering bacon with waxed paper and cooking it, along with liver, in the microwave, a tool popular in the last decades of the twentieth century, which fell out of favor in some circles but is experiencing a resurgence led by chef David Chang. The recipe’s ingredient list feels dated. An organ meat, liver was a popular dish in rural communities in North Dakota in the 1970s and 1980s but is less likely to be served on residential tables now. Moreover, it specifies the use of three processed, brand-name foods: Ritz crackers™, Corn Flake™ crumbs, and Thousand Island™ dressing.

Astonished by almost every aspect of this recipe, I called the contributor, Cathy Knutson, my mother (however, I do not remember ever eating this dish as a child!). She explained that she received the recipe from the local extension agent for the NDSU Extension Agency. This origin makes sense; the use of efficiencies such as processed foods and microwaves reflects the history and influence of home economics, currently referred to as family and consumer science, and the rise of the United States Extension Service, two entities dedicated to improving the lives of American women.

The Goal and Theoretical Context

My posts will contextualize recipes like my mother’s liver slices within broader shifting historical currents, as elaborated upon in research about the US industrial food movement, the history of the field of home economics, and the expectations related to food preparation, pleasure, and practice in the lives of women in North Dakota.

As I ponder the lives of the women who socialized and constructed my understanding of self and home, I find myself reflecting on the society and the expectations that shaped them and their gendered understandings of the division of labor, of their role in their households, and the enjoyment or frustration they may have derived from food and family.

Food is central to human experience, community, and identity. As The Oxford Companion to Food explains, the term “foodways” describes “the food habits and culinary practices of a group of people . . . and the interaction between those habits and their more general circumstances. It might be described as the holistic study of food as it impacts on, and reflects, a defined group.” Cultural food historian Megan J. Elias defines “foodways” in Food on the Page: Cookbooks and American Culture as “the combination of what people ate, how meals happened, and what diners thought about food—which dishes were considered normal, what materials were deemed edible, which preparations are appropriate to which groups” (2).

The foods and recipes used by the women who compiled and contributed to The Joy of Sharing during 1985 in Velva, North Dakota reflect the conventions of this historical moment, the materials and methods available, and the performance of identity and gender. In “The Compiled Cookbook as Foodways Autobiography,” food historian Lynne Ireland asserts that a compiled cookbook creates “in a sense, an autobiography” because “compiled cookbooks make a statement about the food habits of the groups which produce them. Much more than the magazines and cookbooks of the popular press which set standards and attempt to influence consumption, the compiled cookbook reflects what is eaten in the home.”

My project is intended to provide clarity and context, elucidating why these recipes are constructed as they are and illustrating the cultural forces shaping lives at a particular historical moment and in a particular location.

Let’s hope it’s delicious too!

This project is supported by a Centennial Scholars Individual Research Program Grant by Concordia College, Moorhead, Minnesota.