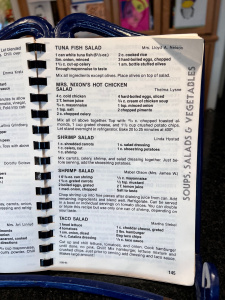

With my shrimp leftover from Dip Day, I tried my hand at “Shrimp Salad” contributed by Linda Hystad, found in the “Soups, Salads, & Vegetables” section.

Shrimp et al.

I ended up needing more shrimp to reach a full cup, and so I thawed and boiled some of the frozen shrimp in my freezer, for just a minute or two, until the shrimp curled and turned pink. I ran cold water over them and cut them up into roughly the same size as the salad shrimp, hoping that the two different types of shrimp would add some nice variation in texture in the final dish. Unlike other recipes in The Joy of Sharing, this one specifies “shrimp” but does not specify an origin—like canned, fresh, or frozen.

Linda instructs the cook to then mix the carrots, celery, shrimp, and salad dressing, and to add the final ingredient, the shoestring potatoes, right before serving to preserve the crunchiness. This is an easy salad to remember—the measurement for every ingredient is one cup!

Salad Dressing?

Though I may be the only North Dakotan with this quandary, I wasn’t completely sure what Linda meant by “salad dressing,” whether she had a particular oily-vinegary bottle in mind called “Salad Dressing.” But my local grocer did not have anything of that sort, nor the type of slender yellow and orange bottle stashed away in my memory as being a generic-type of salad dressing seen somewhere in my youth. Standing in the dressing aisle, I did two things: 1) a quick Google search and 2) a quick call to my parents. Both methods led to the discovery that “salad dressing” is understood to be mayonnaise or even the name brand Miracle Whip. As someone twenty-some years removed from my rural-community-potluck-heavy youth, I now use mayo as a condiment, not a dressing for a salad. Have you tried it as a dip for French fries, as the Belgians and British do? A marvelous usage!

And as an American home cook living at this moment, I expect to purchase, not make my mayonnaise, despite knowing that it is a French sauce. In his fascinating deep dive into the science and chemistry involved in cooking, On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen (originally published in 1984, coincidentally—revised second edition in 2004), Harold McGee lists mayonnaise as one of the five “Classic French Sauce Families,” a modern variation on the original classification of four families of sauces by Antonin Carême (1784-1833) in The Art of French Cooking in the 19th Century (587-88). Mayonnaise is a dense sauce, “an emulsion of oil droplets suspended in a base composed of egg yolk, lemon juice or vinegar, water, and often mustard, which provides both flavor and stabilizing particles and carbohydrates” (McGee 633). In traditional preparations, the egg yolks are raw, though pasteurized eggs can be used to ameliorate the risk of salmonella (McGee 634).

McGee explains that what I find in the supermarket now, what Linda, other contributors, the community who purchased The Joy of Sharing, and my parents, apparently, knew as mayonnaise is an altered version of this traditional sauce; it uses pasteurized yolks, as well as stabilizers, “usually long carbohydrate or protein molecules that fill the spaces between droplets” to avoid the loss of oil that occurs from exposure to extreme temperatures (634-635). He notes the common American moniker with which I was unfamiliar: “American bottled ‘salad dressing’ is a very stable hybrid of mayonnaise and a boiled white sauce made with water instead of milk. The texture of such modified sauces, however, is noticeably different from the dense, creamy original” (635).

And in In Defense of Food: An Eater’s Manifesto (2008), Michael Pollan pinpoints this American shift to a processed mayonnaise to the influence of “nutritionism” (not nutrition) as an ideology, embraced by the Food and Drug Administration and made possible by the FDA repealing a 1938 congressional act regulating imitation foods in 1973 (35). Nutritionism embraced modifying foods to create nutritional equivalences, focusing on the importance of the included nutrients: “the government had redefined foods as nothing more than the sum of their recognized nutrients. Adulteration had been repositioned as food science” (36). After two government reports drawing attention to the links between diet and disease in 1977 and 1982, many “healthier” processed foods like oleomargarine, low-fat products, and other products previously considered “imitation foods” appeared: “hyphens sprouted like dandelions in the supermarket aisles: low-fat, no-cholesterol, high-fiber. Ingredients labels on formerly two- or three-ingredient foods such as mayonnaise and bread and yogurt ballooned with lengthy lists of new additives—what in a more benighted age would have been called adulterants” (Pollan 37). Published in 1985, as these products became available and popular because of their novelty and promises of optimal health and fewer calories, The Joy of Sharing illustrates the reach of the food industry’s altered foods. A journey through the ingredient lists reveals recipes using margarine or oleo, Crisco or shortening, low-fat pudding mixes, skim milk, Miracle Whip, Bisquick, dry and condensed soups, Velveeta and Cheese Wiz, Nestle Quik, Cool Whip, and of course, mayonnaise, aka “salad dressing.”

In my American supermarket filled with foods (or should I say, “foods”?) reflecting this history, I bought my preferred type of manufactured mayo, which is made with olive oil (for a quick overview of the distinctions amongst the types of mayo-based products, like Miracle Whip and those using different types of oils, see, among others: https://www.foodnetwork.com/healthyeats/healthy-tips/2011/07/mayo-good-or-bad and https://www.thekitchn.com/difference-between-mayonnaise-and-miracle-whip-23420166). McGee explains that any type of oil can be used to make mayo, but that unrefined extra virgin olive oil causes mayonnaise to “go crazy,” to separate within a couple of hours of mixing; while Italians are familiar with this craziness or “impazzire” (635), my olive oil mayo manufactured by Kraft does not suffer this fate.

After mixing the ingredients, my verdict is that a cup of mayo is too much in this salad. The vegetables and shrimp were caked in it, and it was no longer clear that this was a salad named for shrimp. I hoped that the shoestring potatoes would soak up some of the mayo, but they didn’t seem to make much of a difference in the texture. I also noted the lack of seasoning mentioned and wondered if the shoestring potatoes were designed to be the seasoning. However, after a quick taste, I decided they did not provide enough salt to combat the overpowering mayonnaise flavor.

Liberties

So I took matters into my own hands. I added two teaspoons of kosher salt, pepper, and cayenne pepper (I was out of sriracha but will try it next time), as well as the juice from one lemon. While I know that this might not have been the intention of the original salad or the contributor, I wanted to see what I could do to make a mayo-based salad more palatable.

It worked, because Luke, who avoids all mayo-based salads (though he’s happy to use it as a condiment), had two helpings. I felt victorious! I thought it was delicious too; it reminded me of the spicy mayo dressing used on poke bowls and some sushi roles. Others agreed. When I brought some to my campus office for my friend and colleague to try, it disappeared from the container very quickly (I did see him eat it—not throw it away, in case anyone started thinking about other possibilities). My friend and neighbor Krystal, who has been making these recipes too (featured soon in a forthcoming post!), texted to say that it “has some good kick to it.” I served only one spoonful to my mother, and despite warning her, she still exclaimed loudly at how spicy it was. Given her central-North Dakota preference for all things mild, I glowed with pride.

Like the shrimp dip, I will make this again, soon. It has “good bones.” This time I will use only a half or even a third of a cup of mayo, more shrimp, and more hot sauce. It would be nice as a salad when grilling or smoking a main dish, but the shift from regular to spicy mayo creates opportunities to make this a side for Asian meals or take-out sushi.

Contributor

Linda (Marshall) Hystad is married to Harry Hystad and raised two children on a farm north of Velva. Though I did recognize Harry’s name, I did not recognize Linda’s, nor was able to find anything about her in the McHenry County book. I did find an entry for Harry Hystad’s parents, Lorentz and Edna. In 1975, Harry purchased the home quarter of his father’s farm, which Lorentz had purchased in 1950 from his father Jens. Though Jens may have homesteaded this land because the dates make sense (I’ll do some further research soon), the entry does not make that claim; instead, it says, “Jens later moved to his own place one half mile south of Mons [his brother]” and that he had first lived with Mons in Mons’ sod house when Jens arrived in North Dakota around 1899-1900, after immigrating from Norway in 1896.

From what I’ve been able to discover, Linda grew up on her parents’ (Clarence and Carole Marshall) farm in the Burlington/Des Lacs area, just northwest of Minot. She must have been quite young when the cookbook was published, but she was an active contributor, with eight recipes: “Sausage Cake,” “Brownies,” “Club Cracker Bars,” “Pizza Casserole,” “Lasagna,” “Pork Rites” (this is a sandwich, a pork-version of the sloppy joe, not a misspelling of “pork rind.” The name alludes to “Maid-Rite”), and “Chocolate Bavarian.”

And “sausage cake” is not a typographical error.

And it’s in the “Cakes, Cookies, & Candy” section.

And I need to make it.

But I need to gear myself up to do it.

This post is part of an ongoing series in which I make and reflect on recipes and the people who contributed them to the 1985 Oak Valley Lutheran Church compiled cookbook, The Joy of Sharing.