For Father’s Day, I decided to find a pie recipe because Luke once joked that he “thought marriage would involve more pies.” We laughed and laughed at that because we are clearly not the type of couple who has those types of gendered expectations of each other (and just celebrated our twentieth anniversary this week). Our lives are very different from our grandparents’ lives. But I assumed there was an element of truth in that statement, given how much he truly loves a great pie (and I did figure out how to make a killer blueberry pie because when you love someone, you make an effort to do things that will bring them happiness, within reason, of course). I didn’t expect marriage to involve so much perfectly-cooked meat and carefully-crafted cocktails, but I’m extremely lucky that it does.

Rhubarb!

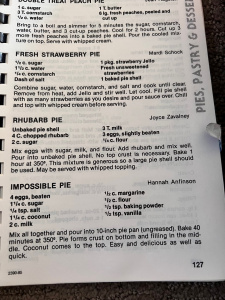

So, given that Luke, my dad, and I love, love, love rhubarb (did I mention that we love it?), I defrosted rhubarb Luke’s aunt had given me and set out to find a rhubarb pie or dessert recipe. I settled on Joyce Zavalney’s recipe from the “Pies, Pastry & Desserts” category. Our daughter and I had just returned home from another delightful week at the amazing Concordia Language Villages (what a fantastic facility! I can’t say enough good things about this program) for a dual day-camp (her) and writing retreat (me!) adventure, and I wanted a recipe which seemed uncomplicated and easy to make on a Sunday morning.

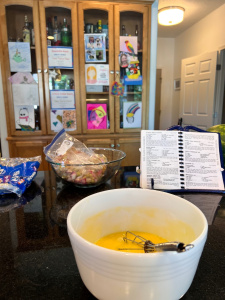

To my relief, this was a straightforward and easy recipe to follow. Mixing was simple, with a base of beaten eggs, sugar, milk, and flour, to which I added the four cups of rhubarb.

It specified an unbaked pie shell, which would be fast and easy, though they’re never as good as home-made crust. But I wasn’t going to argue, especially since I’m mostly interested in the rhubarb filling. I went with a frozen deep-dish shell because the recipe advises a large crust is useful: “This mixture is generous so a large pie shell should be used.”

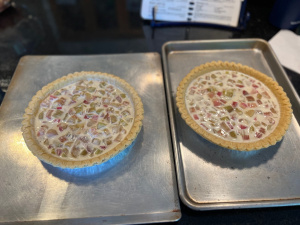

Action photography by The Baby

Indeed, it was. I had enough filling to fill the second of the two crusts in the frozen package. I wasn’t sure what kind of mess would have developed if it I had poured it all in the one shell. I also thought it would be nice to send one home with my dad, given the eponymous festivities. It was ready after being baked for one hour.

My primary question was why “no top crust is necessary.” There isn’t a top crust with the frozen pie shell of course, but the recipe doesn’t specify that it should be frozen, just “unbaked.” I often buy the two-packs of refrigerated pie crusts that need to be unrolled, and I could have used one of those in this recipe. In that case, I certainly could have used the second crust as a top crust; I don’t see any reason to preclude that in this recipe, nor to use my maternal grandmother’s preference—a meringue (the main reason is the poor-quality pie crust, of course). Perhaps a top crust would have been useful, by keeping more filling inside. Not having a top crust is certainly a common way to top a pie, but saying it is unnecessary seems an unusual and quite strong declaration to make.

Reflections

The adults all had poolside pie on that balmy Father’s Day, and we all pronounced it to be tasty (though the crust wasn’t great and didn’t come out onto plates cleanly—it’s not a very sophisticated pie crust, so no surprise there). But the tables turned when my parents asked whose recipe it was; while her name sounded vaguely familiar to me, I didn’t realize it was because this was the sixth-grade teacher who harassed and bullied a student so extensively that the child’s mother had to intervene (which is saying something if it had been severe enough to trigger parental intervention in the 1950s—decades before the rise of intensive parenting and concerted cultivation led to frequent parental monitoring of classrooms). Though rhubarb is tart, this soured the pie for me. It had no impact on Luke; he ate the last two pieces later (not in one sitting).

The project raises the literary critic’s dilemma of how to understand the relationship between art and artist—whether those two entities can or should be considered separately. The New Critics of the early-to-mid-twentieth century focused on the text itself through the techniques of “close reading” and explication and disregarded the author’s intentions and historical context. The author could be divorced from the text. My students continue to struggle with this thorny question today, as celebrities and authors they love say or do things abhorrent to them, like J.K. Rowling, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Lewis Carroll, and so many actors, comics, and producers exposed in the #MeToo movement. Some of the best class discussions we’ve had in the past few years are about these complex issues, and I remain so impressed by the sophisticated, sensitive thinking these young people demonstrate as they try to parse out how to feel when an author of a book beloved by them during their youth says something hateful now, in this complicated world irreparably changed by the ubiquity of social media and the access it provides to artists who might have once seemed more distant, more like figures, not people.

It’s also a great reminder that people are complicated and fallible; that while someone might have had a great experience in a classroom, someone else might not have. That teachers may not treat students equally, equitably, or even kindly. I experienced unfair, cruel treatment from a teacher as a student too and how I felt and never want others to feel certainly informs my pedagogical philosophy and practice today. It continually reminds me to pay attention to my students as multidimensional people. To borrow a literary term, we are all “round characters.”

Contributor

Joyce (Reichert) Zavalney is not included in the McHenry County book, though she and her husband Clarence appear to have lived in Velva in the 1980s. But Clarence was from Butte, a small town southeast of Velva in McLean County, and Joyce grew up nearby in Kief, which is just inside the McHenry County line. There are sundry reasons someone wouldn’t have wanted to or could not participate in the project; location may have been one of them. She was born in 1935 in New York City but moved to Kief at age nine. She taught in Velva for only three years before marrying Clarence and becoming a stay-at-home mother to their four children. She passed in 2016 and Clarence passed in 2021. Her other contributions to the cookbook were “Sticky Caramel Buns,” “Rhubarb-Cherry Jam,” and Crescent Roll Hot Dish.”

This post is part of an ongoing series in which I make and reflect on recipes and the people who contributed them to the 1985 Oak Valley Lutheran Church compiled cookbook, The Joy of Sharing.