Rhubarb Redemption

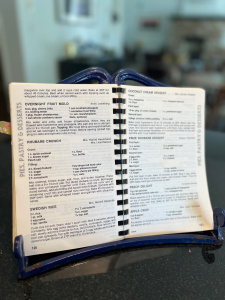

The day after the tater-tot debacle, I dove back into The Joy of Sharing, eager to redeem myself with my family. Retreating to the safety of the “Pies, Pastry & Desserts” section, I selected “Rhubarb Crunch,” contributed by two women listed as Mrs. Harold Henrickson and Mrs. Lloyd Nelson. Given Luke’s love of rhubarb and the Baby’s love of crunch and crisp toppings, I hoped it would be a winner. It was. Mostly.

Process

This was a straightforward recipe. The list of ingredients was conveniently separated into two sections, denoted with introductory colons and spaces. The crust section preceded the filling section and also in the instruction paragraph, the crust section again was first, with repetition of the ingredients for clarity: “Mix oatmeal, brown sugar, salt, flour, and butter together. Press half into a 9 x 13-inch pan.” As I previously have made crisps and crumbles, I knew that “mix” referred not to an electric mixer, but to a utensil first or by hand. I started with the former and moved to the latter to create the crumbs.

This went well, but when I went to press it into the specified size pan, I used much more than the prescribed half of the crust mix. Then I spread the rhubarb across it evenly.

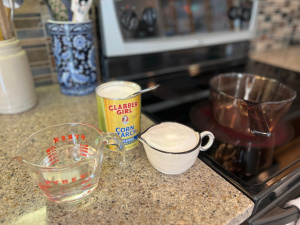

The boiled mixture was fun to watch, and it turned a lovely color when I added the food coloring. While I apparently was out of red, I did have some pink gel food coloring.

The shift from red to pink didn’t make a difference, though, as I next added the can of cherry pie filling, which turned the mixture completely red. The food coloring did not seem necessary.

The cherry pie filling I used had whole cherries, which seemed rather large to me, particularly when I moved to the next step, to “spoon over rhubarb.”

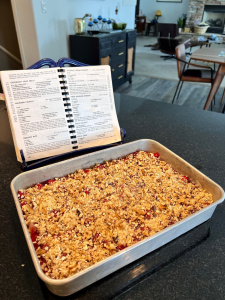

I followed the fruit toppings with the remaining crust mix, which did not completely cover the entire pan, and spread the half cup of “nuts” across the top, attempting to fill in some of the empty spots. When offered a generic category of nuts, once again, I chose walnuts, since I had just bought them at Costco that morning and because they are good for our brains. I do appreciate the agency that the category of “nuts” provides the baker—we are invited to use whatever we wish or have on hand.

The mixture looked gorgeous! I was impressed, and as my daughter wandered by, she commented on how yummy it looked, even before baking.

As instructed, I baked it at 350 degrees for 45 minutes, after which it was bubbling and even more beautiful.

Tasting Reflections

Though the Baby wanted to taste it right away, we let it cool and each had a piece for dessert later that evening. It was delicious. The Baby particularly enjoyed it, undoubtedly because it was very sweet. I think that there is too much cherry all around—too many visible cherries and too much cherry flavor: it overwhelmed the rhubarb. If I did not know this was a rhubarb dessert, I would not have recognized it as one. This is especially interesting, as it is called “Rhubarb Crunch,” not “Rhubarb-Cherry Crunch”—so many other rhubarb desserts, pies, and muffins are labeled to indicate the inclusion of a sweeter fruit, most commonly strawberry. In fact, an internet search for other fruits that pair well with rhubarb leads to articles with titles that point to the strawberry’s ubiquity, like “7 Ingredients to Pair with Rhubarb (Beyond Strawberries)” at The Kitchn and “The Best Fruit to Serve with Rhubarb Isn’t Strawberries” at Tasting Table (spoiler—they recommend dates!).

To temper the sweetness, I would recommend two adjustments: 1) to modify the balance of rhubarb to cherry pie filling, either by using half a can instead of a full can, by using another cup or two of rhubarb, or both, depending on the desired level of tartness; and 2) to increase the crust mixture, by at least half of the specified amount or even double that amount. This adjustment might make the dessert more of a true crunch, as well, rather than remaining more pliable like a crisp or a crumble. As Patricia S. York explains in an article posted at the magazine Southern Living’s website, the traditional distinction between a crisp and a crumble is fine—crisps use oats in their topping; crumbles, only flour—and has now collapsed. Both, however, do not use a bottom crust, which is the distinction between the two and the crunch. The bottom crust allows a crunch to be cut into bars, if possible or desired (for more, see https://www.southernliving.com/food/desserts/difference-crisp-crumble-betty-buckle).

It’s interesting, then, that the crust seemed too skimpy to me—maybe my previous experience with fruit-filled bars made me wish for more topping and more solidity on the bottom. The crunch’s definition also helps explain why the pieces I cut for my daughter and a friend the next day looked more solid, like bars. The Baby’s friend ate hers immediately, Baby noted; this was a well-liked treat by the younger crowd! Whether bars were the original serving intention of the contributors or a potential usage, I still recommend increasing the size of the crust mixture to provide a stronger bottom and top layer to hold in the fruit filling.

We did not follow the final serving recommendation, which was to “serve with whipped cream and garnish with sliced bananas.” Is this a thing? A sliced-banana garnish for fruit desserts? Or any desserts? Is it to rhubarb desserts what cheddar cheese is to apple pie or banana bread (at least according to my partner and my maternal grandfather, among so many others)? Where do you put the garnish? Should the banana be eaten in the same bite as the dessert, similarly to the very common whipped cream topping or any number of desserts garnished á la mode? Does everyone know about banana garnishes but me? In my not-exhaustive searches, the internet doesn’t seem aware of it either. I’m flummoxed.

Also, yay for a recommendation for whipped cream rather than Cool-Whip! It’s one of our favorite things to make. It might temper the sweetness too.

In my piece about tater tot hotdish, I reflected on the cookbook’s recipes that offer multiple variations of the same dish. Here we have a recipe attributed to two people, which suggests that their two separate contributions were identical or at least similar enough to not warrant two separate entries. In an interview with Carolyn Olson, a member of the cookbook committee, she mentioned remembering sitting at her kitchen table with other committee members, sorting through the contributions and puzzling about how to handle duplicates. I think the strategy I can see employed in the cookbook works well—to list all the identical contributions together but to preserve variations when they exist. It offers both credit to the contributors and agency to the readers/cooks to find the variation that will work for their purposes. I am eager to ask some further follow-up questions about duplicates.

Right before bed, Luke told me he knew what would make it even better. I said more crust, right? He said, “well, yes. But then a crust over the top. And then crust on the sides that could be crimped together with the top crust.”

So a rhubarb pie.

Contributors: The Helens

Helen #1: Helen Hendrickson

As there is only one Harold Hendrickson in the McHenry County book, Mrs. Harold Hendrickson (the “d” is missing in the cookbook—typos happen in words with eight consonants) appears to have had the given name Helen. At her birth in Falsen Township (east of Simcoe, north of Karlsruhe; the only remaining “town” in the township is Verendrye) in 1908, she was named Helen Nerem. Her parents, Mathias and Hannah Nerem, moved from this homestead in 1913, to a farm east of Deering, ND. After graduating from high school there in 1927, she attended Minot State College for one summer before marrying Harold Hendrickson in 1928,the son of Lars and Berget Larson Hendrickson, born in 1906.

Harold’s parents have a fascinating story in the McHenry County history book, also written by their daughter-in-law, Helen (again signed Mrs. Harold Hendrickson). Lars and Berget boarded the same boat to immigrate from Norway in August 1900, both with the intention of homesteading. Berget’s was in Rosehill Township (just to the north of Falsen); Lars’s in Falsen Township. Helen mentions that Lars and Berget previously knew each other in Norway, as they were both from Nes, Hollingdal, but it seems they did not intend to immigrate together. It’s not clear whether they socialized on the boat or how they traveled to McHenry County once they arrived in the United States. But clearly romance ensued (of some sort…at some point).

Harold grew up on these homesteads, as well as another farm the family purchased in 1914, in Villard Township just to the east of Falsen. Later, Harold became a Cobber, taking a short business course at Concordia College in his youth. We didn’t have Niblet or Kernel yet, though.

After a year in Wolf Point, Montana, the couple returned to Falsen Township to farm on Lars’ homestead, which they did until the 1970s, though they moved into Velva in 1956 and joined Oak Valley in 1958. Helen describes herself as “active in all church affairs and . . . also active in PTA. She held offices in both. She was also self-employed as a dressmaker for many years.” They had seven sons (Arlyn, Dale, Lyle, Robert, Manville, Roger, and Ardell), and by 1985, had had twenty grandchildren and ten great grandchildren. Helen passed in 1995; Harold in 1996. In addition to this rhubarb crunch, Helen contributed “Deluxe Waffles,” “Molasses Cookies,” and “Cucumber-Carrot Relish.”

Helen #2: Helen Nelson

Again, if my research and deduction is correct, then Mrs. Lloyd Nelson was also a Helen, Helen Thorson, from Kendall County, Illinois, born in 1923. The “Lloyd Nelson” referred to in the moniker used by the contributor of “Rhubarb Crunch” was also born in 1923, but in LaSalle County, Illinois. In 1943, they married in Honda, Texas, which is a pretty amazing name for a town. After serving in World War II, Lloyd attended Luther Seminary in St. Paul, was ordained in 1958, and served as a pastor in other ND communities—Milnor and Emerado—and as a chaplain in Grand Forks. He was the main pastor of Oak Valley from 1982 to 1985, during the publication of The Joy of Sharing. Helen worked as executive secretary to the CEO of Klein’s grocery stores in St. Paul, to a commander at the Grand Forks Air Force Base and the director of the USDA-ARS Human Nutrition Research Center. The couple had three children: Constance, Cynthia, and Lloyd Jr. She passed away in 2021; he in 2015. Helen contributed five other recipes to The Joy of Sharing: “Mandarin Orange Cake,” “Minute Fudge Frosting (Old),” “Salmon Ring,” “Norwegian Apple Pie,” and “Tuna Fish Salad.”

The “Mrs. Husband’s Full Name” Title

As I noted in the post about Chocolate Marshmallow Squares, naming practices in Anglo-American cultures have obscured the visibility of women’s families of origin. With no given name listed, both Helens who contributed this rhubarb dessert are further obscured. Using the honorific “Mrs. Husband’s Full Name” as a title was not uncommon in 1985; at least one of my grandmothers (coincidentally, also a Helen…maybe they don’t like their given name? But she launched a thousand ships!) preferred it into the 2000s, even signing checks this way and writing occasional checks addressing me like this (umm…that person doesn’t legally exist, but no matter…).

Stephanie Coontz, the family historian who wrote the landmark text, Marriage, a History: How Love Conquered Marriage as well as The Way We Never Were: American Families and the Nostalgia Trap, explains in an interview in The New York Times that the use of “Mrs. Husband’s Full Name” began in the nineteenth century and was a popular usage for married women by 1900. It was used fashionably by wealthy women and as others adopted it, used to signal “pride in their wifely identity” in adherence with the rise of an ideology known as the “cult of domesticity” or “the cult of true womanhood” (Chambers, Padnani, and Burgess, see https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/15/arts/mrs-women-identity.html). As historian Megan J. Elias describes in Stir it Up: Home Economics in American Culture, in the 1820s, this ideology prescribed an idealized role for American women:

They were also encouraged to think of their lives within the home as sacred and the work they performed there as vital to society. This ideal, generally known as the cult of domesticity, identified woman’s highest calling as thoughtful wife and mother. As material production retreated more and more rapidly from the home, women acquired new roles as spiritual guardians and also as consumers of mass-produced goods. By necessity these ideals, propagated in popular fiction and women’s magazines, applied only to the middle and upper middle class, but such women were supposed to serve as models for all women. (4)

The cult of domesticity tied women’s identity to martial status, hence the rise of titles reflecting that status. As Emily Post’s Etiquette website explains, in the US, “Miss” was originally for unmarried women, but now is for young women under 18, whereas married women have a few different options:

Traditionally when a woman married she would automatically become Mrs. Husband’s First Name Married Last name (Mrs. Jon Rooney). Her entire identity was framed around her husband. Today this tradition is an option for those who value it. Moreoften [sic], when a woman chooses to marry (no matter whom she marries) she chooses whether to remain a Ms. or to adopt the married title of Mrs. She may also choose to keep her surname or to adopt a new surname. And if she does adopt her partner’s surname she has the choice of being known in the traditional form by his full name (Mrs. Jon Rooney) or if she’d like to be known by her first name and the family surname for example Mrs. Christine Rooney.

Many women’s displeasure with this limiting system led to some creative thinking and the advent of the title of “Ms.” in the 1970s (introduced by Ms. Sheila Michaels: see https://www.nytimes.com/2017/07/06/us/sheila-michaels-ms-title-dies-at-78.html). Delightfully, Emily Post’s website introduces this title as “The Game Changer” (which it is!) and explains that “Ms. is the adult title for those who identify as women and either are independent or are married but wish to use the title Ms. instead of Mrs. Ms. came into being in the 70’s and has been a game changer. It allowed for married and unmarried adult women to have a title that was on par with Mr. (which can be used for married or unmarried men) and also meant that their marital status need not be declared with every mention of their name.” And in their “Guide to Addressing Correspondence,” these etiquette gurus remind the readers of the elegant solution that is “Mx.”: “Mx. Is the universal title that can be used by anyone. It is gender non-identifying. Even if you identify specifically with a gender you may still use Mx. and you may see Mx. used when the sender is unaware of your title.”

As I’ve previously mentioned, I love talking about names, and titling practices are similarly fascinating. This topic comes up so often in my grammar and editing course, and students share the bizarre things they’ve learned about what these various titles mean (some were told “Ms.” indicated a divorced woman. Wow…talk about identifying women by martial status. How charming). It’s much easier for students to navigate this minefield in college, as professors typically ask students to use their first names or “Dr.” if their terminal degree is a Ph.D.

Given the apparent nation-wide confusion about women’s titles, I’m so thrilled to see that the Emily Post guide, which many people might have expected to be a bastion of “tradition” and “correctness,” adheres to what I think is the epitome of “correctness”: foregrounding respect when addressing others: “Traditionally, how a woman was addressed when using titles had to do with identifying her marital status. Ironically, titles are supposed to help identify us, and this limiting system left many women out of feeling properly addressed. It also left adult women with no option other than to remain a “Miss” or use no title, options that were lackluster at best. Thankfully times have changed, an individual’s personal title preference is the proper way to address them [emphasis mine]” (https://emilypost.com/advice/ms-miss-or-mrs-whats-the-difference#google_vignette).

Clearly, the contributors who submitted using the “Mrs. Husband’s Full Name” form preferred it. However, its usage has made it difficult to recognize who they were in my project, and in other projects too. In 2020, Amisha Padnani and Veronica Chambers published a series of articles in The New York Times examining honorific title usage, inspired by identifications of women in the photos and files in the Times’s archives. And Lori Nohner, Assistant Curator of Collections in the Audience Engagement and Museum Division at the State Historical Society of North Dakota, discussed her work attempting to discover the first names of women referred to in this way in the historical society’s artifacts and records (https://blog.statemuseum.nd.gov/blog/beyond-mrs-husbands-name-researching-womens-full-names). Nohner astutely explains the reason for continuing to identify who these women actually were:

The State Historical Society has artifacts and records attributed to women around the state using their husband’s names. We don’t know if they did this simply because it was the social norm, or if that was their preferred title. Perhaps early record keepers made the decision for them. Whatever the reason, documenting the women’s full names builds a richer and more complete picture of North Dakota’s history.

I wholeheartedly agree.

This post is part of an ongoing series in which I make and reflect on recipes and the people who contributed them to the 1985 Oak Valley Lutheran Church compiled cookbook, The Joy of Sharing.