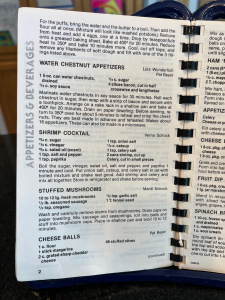

Shrimp Cocktail

Next, I prepared Verna Shock’s “Shrimp Cocktail” so that we would have a second dip for our afternoon snack. We enjoyed this as well, especially its versatility.

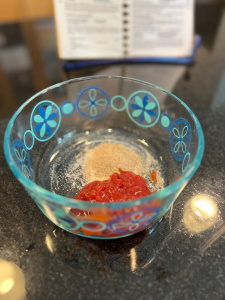

Here again was another blissfully straightforward recipe. My only question was how much celery to use (hint…I would use more in the future). I boiled the listed ingredients, as prescribed, and then added the mixture, when cooled, to the other mixture I was supposed to prepare—a combination of catsup, celery salt, and onion salt. Since I didn’t have onion salt, I used garlic salt, a substitution I hope didn’t make much of a difference.

Aside on Terminology: Ketchup vs. Catsup

While I prefer the term “ketchup,” several recipes in this book, as well as speakers in the central ND region use the variant “catsup.” Google searches indicate that it’s quite the linguistic debate, and my favorite authority (because it’s the best) on language usage, which should be yours too—the Oxford English Dictionary or OED—indicates that both terms for this sauce were in use as of the seventeenth century, with “ketchup” recorded as early as 1682, in a book titled so beautifully and specifically that I have to include it entirely: The Natural History of Coffee, Thee, Chocolate, Tobacco, In Four Several Sections; With a Tract of Elder and Juniper-Berries, Shewing how Useful they may be in Our Coffee-Houses: And also the way of making Mum, With some Remarks upon that Liquor: Collected from the Writings of the best Physicians, and Modern Travellers (here’s a link to the digitized book and its title page—note I did adapt for modern spelling of “s”: https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-8708693-bk). “Catchup,” the variant spelling of “catsup,” and one more recognizable, given the ubiquity of the spelling of “ketchup,” was used as early as 1696, in John Floyer’s The Preternatural State of Animal Humours Described by their Sensible Qualities.

The OED notes that “ketchup” referred to a more “piquant sauce produced in southeast Asia, probably made from fermented soybeans or fish.” The entry for ketchup as a noun provides a useful historical note on the nature of this sauce/condiment:

The word ketchup first appears in English in the 17th cent. with reference to a type of sauce encountered by British travellers, traders, and colonists in southeast Asia and introduced to Britain by them. Similar sauces referred to as ketchups appear from the 18th cent. using a variety of ingredients, anchovies, mushrooms, walnuts, and oysters being particularly popular. From the late 19th cent. tomato ketchup became the most popular form.

Directing the inquirer to the entry for “catsup,” the OED provides further context for the additional name: “Perhaps as a result of influence from major commercial brands of sauce, ketchup seems to have become the dominant term from around the middle of the 20th cent., although catsup is still well attested in North America.”

And if you want to be particularly clear that you are referring to the modern ketchup, rather than the pre-nineteenth century, more savory version, then you may also call this concoction “tomato ketchup or tomato catsup,” a usage which was first recorded in 1845, in British food writer Eliza Acton’s Modern Cookery in All Its Branches and which became “Chiefly U.S. after mid 19th cent.” Unless you have a subscription to the OED, these entries will be unavailable to you, but here are the links, for thoroughness:

- Ketchup: https://www.oed.com/dictionary/ketchup_n?tab=meaning_and_use#40121470

- Catsup: https://www.oed.com/dictionary/catsup_n?tab=meaning_and_use#9836780

- Tomato Ketchup: https://www.oed.com/dictionary/tomato-catsup_n?tab=meaning_and_use#1218505540

So call it what you wish, Americans. I remain attached to ketchup because I think it sounds more melodious, though I don’t love knowing that commercial practices have influenced my usage.

Back to the Recipe…

Although I did not have a large enough jar for shaking the two mixtures to combine them, as recommended, I wished I had, as my Pyrex lidded container did leak a bit. I’m sure I just didn’t have it on tightly enough. I added thawed frozen shrimp (again, no cans to be found—I need to try more than the three stores I regularly go to) and the celery, before putting it in the fridge with the peppered cheddar dip.

Verna instructs the cook to “store in refrigerator and shake before serving,” but I wasn’t sure if refrigerating it is a storage tip or a blending-for-taste tip. In any case, I decided to let it rest in the fridge in case further blending was possible and pulled it out two hours later with the peppered cheddar dip for our afternoon snack.

While plating our snack, I took a taste of the shrimp cocktail and thought it was a bit sweet, so I added some cayenne pepper and hot sauce. I served it with tortilla chips, mini toasts, and tostadas, since the mixture of seafood, vegetables, and spices reminded me of ceviche (which our family cannot get enough of. Ever). The presentation of the dip was beautiful!

Despite adding more spicy ingredients, it still seemed a bit sweet for my taste—more like a barbecue sauce than a savory shrimp ceviche. That’s undoubtedly the sugar and the ketchup, which I would reduce if I made this again. I also would add more cilantro, minced garlic, onion, and lemon juice (yes, I know that makes it like a ceviche. But wouldn’t that be good too?), in addition to more shrimp and celery. It’s a good recipe and a fun one. I will follow up with Verna to ask for serving recommendations.

Micheladas!

Because the shrimp cocktail was sweet and spicy, Luke had a brilliant idea. Inspired by our love for a michelada, the classic Mexican beer cocktail, he put about four spoonfuls of shrimp cocktail into the bottom of a glass, added a light beer (certainly this was not the right day to be out of Modelo!), and clamato. It was tasty!

Unlike so many other cocktails, there’s a lot of flexibility with micheladas—to vary the savory components, to add solid garnishes (shrimp, avocado, cucumbers, and in more extreme cases, sprinkles, and gummy worms)—they offer the creativity and agency of a Bloody Mary or Bloody Cesar.

Several resources outline the mythical and conflicting origins of the cocktail, as well as its meteoric recent rise in popularity. Useful overviews and recipes are provided in the Netflix documentary Heavenly Bites: Mexico (the first episode is devoted to the michelada), the venerable The Oxford Companion to Spirits and Cocktails edited by David Wondrich with Noah Rothman (*see footnote below for details regarding Wondrich’s amazing CV, the role model for English professors everywhere) and these articles: “The Battle for the Craziest Michelada is On. But How Much is too Much?” by Daniel Hernandez in The Los Angeles Times (https://www.latimes.com/food/story/2022-08-11/michelada-history-beer-drink-los-angeles-mexico-market) and “Behold the Michelada, the Beer Cocktail That Rules Brunch” on Wine Enthusiast’s website: https://www.wineenthusiast.com/recipes/cocktail-recipes/best-michelada-recipe/.

Wondrich uses the apt adjective “murky” to describe the michelada’s emergence. Continuing further, he notes that “one oft-cited account tells of a man named Michel Esper creating the drink at the Club Deportivo Potosino in San Luis Potosí in the 1970s; Esper, a civil engineer, has come forward with details to back up the story.” Some accounts of this story provide further details, explaining that Esper was suffering from a hangover when he arrived for a round of tennis at the aforementioned country club and that his requested combination of ingredients reflect his desire to create a “hair of the dog” beverage (see Wine Enthusiast from above, among others).

The other popular origin narrative is delightfully linguistic—it suggests that “michelada” is a portmanteau, two distinct words blended together to create a new word with a new meaning that harkens back to the original words’ denotations or associations (e.g. “brunch”). Noting that both the story about Esper and this linguistic explanation are “plausible,” Wondrich continues: “the word Michelada derived from the Spanish words for “my cold blonde”: mi chela helada; “blonde” in this case referring to a light beer, such as a lager or pilsner. It’s also possible that chelada is simply a Spanish adaptation of the English word ‘chilled.’” And in an article published when he was senior drinks columnist at the Daily Beast, Wondrich does an even deeper dive into the multitude of other theories (https://www.thedailybeast.com/the-mysterious-case-of-the-michelada-beer-cocktail).

Just like any other cocktail, really good micheladas are crafted from mixing ingredients—clamato and the canned versions that some beer companies (Budweiser and Modelo, among others) are selling are shortcuts. In The Oxford Companion to Spirits and Cocktails, David Wondrich defines this cocktail as “a popular Mexican mixed drink made with beer, lime juice, and hot sauce. It frequently also includes Worcestershire or soy sauce or the umami-rich liquid what-gluten seasoning called Maggi (a popular MSG product found in cuisines around the world) and a salt rim.”

Our shrimp-cocktail michelada wasn’t the best michelada I’ve ever had, but it hit the spot on a hot afternoon. It was, as Luke said, “restorative,” a term reflecting one of the drink’s purported original purposes as a hangover remedy. On hot days, I prefer the lighter, refreshing “chelada” version—lime juice, salt, and a lager or pilsner. But I love the flavor of a carefully crafted michelada, like one I had last December in Puerto Vallarta (and not just because it was my first drink in the pool on our first afternoon of vacation). This michelada was the most refreshing and flavorful michelada I’ve ever had, with Pacifico, lots of lime, salt, and fresh ingredients mixed to create umami. But I could not have more than one of those, or even one every day—it was so filling.

Okay…now I’m thirsty. Is it (shrimp) cocktail time yet?

Contributor: Verna Shock

Verna (Gjellstad) Shock was born in 1925, to Conrad and Anna Gjellstad, near Verendrye. She attended primary school in Verendrye, high school in Velva, Concordia College (yay!) for one year, and then transferred to Minot State Teachers College. She began her teaching career in Turtle Lake (about forty miles south of Velva), where she met her husband, Emil Schock. Born in 1919, to John and Christina Schock of Turtle Lake, Emil attended Mayville College and enlisted in the National Guard in 1941, serving in the 164th Infantry during World War II. They married in 1946 (and were married for the next sixty-four years), and she continued teaching in Turtle Lake while Emil worked as a mail carrier.

In 1949, the couple moved to live near Verendrye; Emil farmed, and Verna continued teaching in Simcoe and Velva, continuing with fifth grade for the first fifteen years of her career, followed by subbing for the next twenty-five years. When we met for an interview, she told me that she had subbed in every classroom in the Velva school except the computer classroom. She also taught piano lessons. In 1981, the Shocks moved to Velva, transferred their church membership from Verendrye Lutheran Church to Oak Valley, and became active in Oak Valley and the ALCW.

They also collaborated on an engaging pastime—from 1971 to 1996, Emil built 366 wooden stools, and Verna painted Norwegian-inspired designs and the names of families on them. Many families from the Velva area have these stools, which Verna calls “Grandpa Boxes.” Her father started the tradition of making these wooden boxes, and her sons gave them their charming name. In 2001, she painted a final stool to honor a special request. Both my Knutson and my Christensen grandparents (who were not from Velva—this is how popular the stools were!) had these stools, and both stools now sit in my parents’ living room. I had never realized that Verna and Emil had made them. This was truly a delightful surprise.

Verna and Emil had two sons, Jerome and Joel, five grandchildren, and several great-grandchildren. Joel’s wife Mardelle, who goes by Mardi, was the president of the A.L.C.W. in 1985, and the person who proposed publishing an A.L.C.W. cookbook. Verna joined the Cookbook Committee and organized the recipes into their present order within each category. She told me she loves to cook and about how she learned to cook as a newlywed, using a Better Homes and Gardens Cookbook received as a shower gift. The first thing she learned to bake was bread, and she continued baking buns until very recently. Indeed, she always made buns, bread, caramel rolls, or cinnamon rolls if company was coming over and became famous for her buns. She reported, “‘people would say, ‘Oh, boy! We get Verna’s buns!’” She also loved to catch, prepare, and eat fish (four of her twelve contributed recipes are seafood-related), and because she and Emil had a “beautiful boat and camper,” they could easily go fishing together. Verna still carries her own jar of the “Cucumber Relish” recipe she included in The Joy of Sharing to use as a tartar sauce for fish dishes.

Verna is a vibrant 98 years old—she’s never worn prescription glasses and does not take any prescription medication. She misses cooking but still makes her own breakfasts and dinners and told me she loves egg salad sandwiches for her evening meal. And she’s an active member of her community, visiting with many people each day, and baking her own Norwegian sweets to have on hand for visitors. As she sent me home with homemade sand bakkels and krumkake, I can attest that she is an excellent baker. In addition to “Shrimp Cocktail” and “Cucumber Relish,” Verna contributed another ten recipes to the Oak Valley cookbook: “Date-Nut Muffins,” “Graham Cracker Bars,” “Sand Bakkels,” “Norwegian Dumpling Soup,” “Runny Chokecherry Jam,” “Scalloped Fillets,” “Pickled Fish,” “Pistachio Cream Pie,” “Mardi’s Salad,” and “Scalloped Cabbage.”

*Footnote on David Wondrich

Holding a Ph.D. in comparative literature from New York University, Wondrich’s first career was professing English at St. John’s University in New York. Dr. Wondrich’s current career is cocktail historian and author! Published on both Flaviar.com and the book jacket of The Oxford Companion, what must be his preferred official bio outlines his vocational transition: “A former English professor, his long-time interest in the arcana surrounding spirits and cocktails led him to leave academia to become Esquire Magazine’s drinks correspondent, and later senior drinks columnist at the Daily Beast. He has written four books on drinks: Esquire Drinks, Killer Cocktails, Imbibe! (the first cocktail book to win a James Beard award), and Punch.” In 2022, The Oxford Companion won the American Library Association’s Dartmouth Medal, a prestigious award given to the year’s “most outstanding reference work” (https://rusaupdate.org/2022/01/dartmouth-medal-for-excellence-in-reference-awarded-to-the-oxford-companion-to-spirits-and-cocktails/). He serves as Flaviar’s Resident Spirits and Cocktails Historian and Advisor, writing articles appearing on their blog; Luke listens to him on their podcast. And this is a brief overview of selected items from his long cocktail-related CV. I bet he misses grading papers, though…

See, I’m not kidding—English skills are the most transferable, flexible tools any of us can develop.

This post is part of an ongoing series in which I make and reflect on recipes and the people who contributed them to the 1985 Oak Valley Lutheran Church compiled cookbook, The Joy of Sharing.