Garlic bread is a classic side with pasta in the United States, and it certainly is a favorite at our house. In a rush, we’ll pick it up at the grocery store, but with more time, I’ll make the gooey, cheesy masterpiece that is Chrissy Teigen’s “Armadillo Cheesy Garlic Bread,” from Cravings: Recipes For All the Food You Want to Eat. If anything ever deserved an exclamation of “chef’s kiss!,” it’s this armadillo-shaped indulgence.

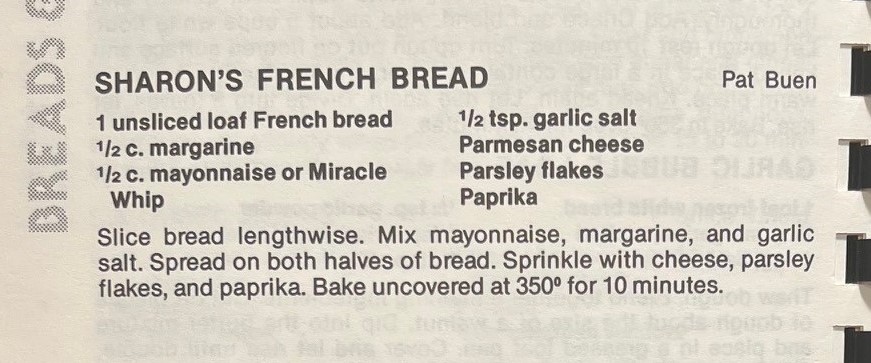

“Sharon’s French Bread” had been on my mind since several contributors I interviewed recommended it, and this rendition did not disappoint. Pat Buen’s contribution appears in the “Breads & Rolls” section of The Joy of Sharing.

Process

The first ingredient, “1 unsliced loaf French bread,” refers the cook back to the dish’s title, keeping the focus on the bread itself, and the first sentence of the instruction section offers an imperative related to this bread: “Slice bread lengthwise.” When I made this bread the first time for our movie night, slicing offered a bit of an adventure, given the almost two feet of French bread in front of me on the cutting board. Needless to say, I did not get it sliced exactly in half, but I did get it sliced—evenly enough that I wasn’t worried about one side getting done earlier than the other.

The rest of the preparation was simple and swift. I mixed the half cup of mayonnaise (I prefer the type made with olive oil) with half a cup of softened butter, rather than the prescribed margarine, though I thought the half teaspoon of garlic salt wouldn’t be enough to season a cup of mayo and butter with enough garlic flavor. So I added more—another half teaspoon of garlic salt, thinking, “We’ll see!”

Despite the long loaf of bread and a heavy-handed spreading technique, ample topping remained. Perhaps I was not liberal enough with my topping. Or maybe the instructions did not indicate that this recipe makes enough for multiple loaves. But I doubt that would have been omitted, given the clarity of Pat’s imperatives to “slice…mix….spread…sprinkle…and bake.”

The last few ingredients offered opportunity to adapt to the cook’s preferences, with no amounts prescribed for how much parmesan, parsley flakes, and paprika to sprinkle on each half. After using a microplane to grate Parmesan for both the bread and for the lasagna, I used enough cheese to cover the mayo/butter/garlic salt spread. I also took the liberty of sprinkling one of the halves with red pepper flakes.

A Golden Beauty

Each half went directly onto the oven racks, baking for ten minutes at 350 degrees. When they looked golden on top and bottom, I used Luke’s barbecue gloves to pull them out and let them rest a few minutes before cutting thick wedges. And the bread’s color looked even better sitting on the kitchen island in the evening light, with flecks of red pepper, green parsley, and Parmesan varying in shade from white to golden brown to red, when tinged with paprika.

These elements also created attractive textural differences because of the asymmetrical nature of parsley flakes, the scattering of sprinkled paprika, the melting of the spread down the side of the loaf. When we look even more closely, you can see the miracles wrought by Parmesan, which melts but remains visibly distinct after being grated. Parmesan’s behavior is unlike other cheeses whose grated pieces melt together, a feat explained by Harold McGee in On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen; McGee notes that “Melting behavior is largely determined by water content. Low-moisture hard cheeses require more heat to melt because their protein molecules are more concentrated and so more intimately bonded to each other; and when melted, they flow relatively little” (64).

After we dished up these beauties and moved to the living room for our movie, I promptly realized the garlic bread was definitely too salty, courtesy of the extra garlic salt and the Parmesan. Indeed, Alex Delany, writing for bonappétit.com, calls Parmesan “the undisputed heavyweight champion of hard, salty, tangy dairy products.” Both Delaney and Food Network Kitchen (among others—this is common knowledge, but I like to cite my sources) point out that while Parmesan deserves its salty reputation, one must be cautious when substituting similar cheeses, like Pecorino, known to be “a tad sharper than Parmesan and a hell of a lot saltier,” as Delaney notes. While outlining the cheesemaking process, my favorite food scientist McGee reminds the reader that “the cheesemaker always adds salt to the new cheese, either by mixing dry salt with the curd pieces or by applying dry salt or brine to whole cheese” (61). Salt benefits cheese because it adds flavor, “draws moisture out of the curds, firms the protein structure, slows the growth of ripening microbes, and alters the activity of ripening enzymes” (61). McGee also points out that the typical cheese has salt by weight between 1.5 and 2 percent but that pecorino “may approach 5%” (61). Parmesan is somewhere in between.

However, no one eating “Sharon’s French Bread” for Puss in Boots Movie Night complained too vigorously of needing a desalination tablet. The bread was subsequently devoured.

And I’m pleased to report that when I made this again, I used the prescribed amount of garlic salt—the ½ teaspoon—and it was perfect.

Garlic!

But I began to wonder—why does this recipe use garlic salt rather than garlic powder? What is the difference between the two seasonings? And what do other garlic spread recipes prescribe?

Once a much-maligned seasoning reviled by the likes of James Beard and Julia Child, its stability and utility led to a recouping of its reputation; see Genevieve Yam’s fascinating overview of garlic powder’s reputation: https://www.epicurious.com/expert-advice/garlic-powder. Garlic powder is made from grinding dried garlic cloves into a fine consistency—a powder, if you will. While it can be used in many dishes calling for fresh minced garlic, it isn’t an exact substitution. Rather, it should be used to season dishes that are moisture-sensitive (https://www.tastingtable.com/1108895/when-to-use-garlic-powder-vs-granulated-garlic/), to blend into a mixture without changing its textures (Yam), and “to lightly and evenly coat foods” like popcorn (Rambauer 989).

Since garlic salt is made of the two ingredients in its name, a mixture of garlic powder and salt, it adds both of these flavors to dishes. That means that recipes using salty ingredients or salt itself should be adjusted to accommodate the extra salt in garlic salt; for example, in an interview with Isadora Baum in Southern Living, registered dietician Lauren Harris-Pincus recommends reducing the salt in such a recipe by half and using it when you want a salty flavor, such as “in rubs for meats and sprinkling on veggies, popcorn, and eggs” (https://www.southernliving.com/garlic-salt-vs-garlic-powder-8584644).

So it’s interesting that Pat Buen’s recipe—sourced from some “Sharon” who loves garlic bread—calls for garlic salt and Parmesan cheese. The 2019 edition of Irma S. Rombauer’s 1931 classic cookbook Joy of Cooking (its ninth edition, edited and expanded by the husband and wife team of Rombauer’s great-grandson John Becker and Megan Scott), highlights the conundrum inherent in this recipe, referring to garlic salt as “a fine seasoning with similar uses” to garlic powder, “but we enjoy the freedom of adding them separately, and to taste” (989).

Adding the flavor of garlic—with fresh garlic or garlic powder–separately is certainly the method recommended in other recipes for garlic bread. My brief survey online and of my cookbook collection indicates these two ingredients as the most popular vehicles for garlic flavor.

Recipes advocating for garlic powder include those for garlic bread and biscuits in the Velva centennial community cookbook from 2005, a bread called “Garlic Bubble Loaf” by the Morton County FCE Club, in the North Dakota Association for Family and Community Education’s 1996 cookbook, Fun Cookin’ Everyday, and Tudi Henderson’s version of “Garlic Bubble Loaf” (I can’t wait to make that too!) also in The Joy of Sharing.

Many other cooks and cookbooks recommend using minced, grated, or finely chopped garlic cloves in a butter spread or rubbing gloves directly on toasted bread. Using cloves in a spread is prescribed in the recipes for garlic bread in Rombauer, Becker, and Scott’s Joy of Cooking (638); in “Grilled Garlic Parsley Cheese Bread” from Steven Raichlen’s essential 2001 cookbook, How to Grill: The Complete Illustrated Book of Barbecue Techniques (420-21); in “Garlic and Herb Butter” in Ina Garten’s Go-to Dinners (55); and of course, in the aforementioned “Armadillo Cheesy Garlic Bread” in Teigen’s 2016 publication, Cravings (154). Building upon the Italian tradition of bruschetta, Garten also recommends rubbing garlic cloves on warm pieces of baguette in 2014’s Make it Ahead, as does Meathead Goldwyn in his eponymous 2016 cookbook, Meathead: The Science of Great Barbecue and Grilling, though the rubbing occurs before grilling in his version.

Interestingly, Betty Crocker’s The Big Red Cookbook ninth edition, published in 2000, recommends either form of garlic, 1 to 2 chopped cloves or ¼ to ½ teaspoons of powder, in both its recipe for garlic butter (458) and garlic bread (86). I like to think that Betty Crocker is providing the cook with agency—letting us choose the texture.

In the end, I’m not sure why “Sharon’s French Bread” uses garlic salt rather than garlic powder or fresh garlic. Nevertheless, I do think it has to do with the time and the place.

Maybe fresh heads of garlic were not often or ever available in a small community grocer. Maybe fresh garlic was seasonal. Or maybe busy families, especially farm families living outside of town, didn’t have time to hit the grocery store too often—let alone the larger markets in neighboring Minot. I imagine some people grew their own garlic in the summer, but the brief season—only three to four months to grow and harvest fresh ingredients—led to the adoption of preservation techniques, such as making garlic powder. Maybe mincing your own garlic became popular with the advent of the Food Network, the rise of specialty cookbooks, and the focus on fresh, whole ingredients as everyone became foodies. I know I learned why and how to do it from Giada De Laurentiis and Alton Brown in the early 2000s.

Or maybe Sharon really, really, really likes salt.

I get it. I do too. I’ll take a heaping basket of salty tortilla chips and guacamole over a chocolate lava cake any day.

This Title…and More Questions

Essentially, this recipe provides instructions for creating a garlicky topping and a method for applying it to a loaf of French bread.

Question 1: So why is it called “Sharon’s French Bread” and not “Sharon’s Garlic Bread”?

I really don’t know the answer to this one. It’s a mystery, much like why “catsup” became a popular pronunciation for the condiment I prefer to call “ketchup.” For a deep dive into that linguistic history, see my previous post: https://blog.cord.edu/karlaknutson/2023/07/31/food-for-fun-in-the-sun-part-ii/.

Questions 2 &3: Why is French bread the appropriate bread to use with a garlic-butter topping? Why are we crossing national cuisines lines?

We’re actually crossing oceans too. Garlic bread is the creation of Italian American immigrants, not of Italians in the homeland. The latter folks have been doing what Meathead and Ina recommend—toasting bread, brushing it with olive oil, and rubbing it with garlic cloves since the 1400s in Venice, according to John Tolley in his article, “The Italian American Origins Of Garlic Bread” (https://www.tastingtable.com/1524906/garlic-bread-italian-american-origins/). This is bruschetta. The former folks arrived in the US in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and had difficult finding ingredients common in Italy, like olive oil. As Tolley explains, “More readily available were French bread, or baguette, and butter. Knowing that both Italians and Americans enjoy bread with their meals — especially when there is sauce to be sopped — chefs wanted to provide diners with a flavorful approximation of bruschetta. Bread was topped with plenty of butter, toasted until crispy, rubbed with raw garlic cloves, and, maybe, sprinkled with herbs or parmesan.”

Moreover, French bread, or the most common type of French bread referred to with this name, is perfect for garlic bread, with a crusty crust and according to renowned French bread expert Raymond Calvel, a “creamy white crumb” (qtd. in McGee 543). The crumb is the “sponge-like network of starch and protein filled with millions of tiny air pockets” that forms the inside of bread (McGee 521). Topped with butter and often cheese, French bread’s chewy center provides a permeable foundation for two melty, gooey ingredients. Yum, indeed.

Question 4: Maybe most importantly, who is Sharon?

Actually, I have a pretty good guess about how to answer the final question. Sharon Hoff, aka Mrs. Hoff, was my sixth-grade teacher, married to Mr. Hoff, my high school physics and chemistry teacher. The Hoffs lived next door to the Buens, and as I noted in my previous posts about Pat Buen’s recipes, Pat’s husband Gene had a long career teaching math and coaching baseball in Velva. I’m guessing this is another of those recipes shared amongst friends, after an expression of admiration.

Yet, I may be wrong, as there are certainly more “Sharons” in the world than Mrs. Hoff. In fact, Pat’s sister-in-law, is another Sharon—Sharon Wilson, married to Pat’s brother Jim. And though I checked, none of the other contributors to The Joy of Sharing are named “Sharon,” which implies that the eponymous Sharon is not part of the contributing community within the Oak Valley women’s group, though there may have been more people named Sharon in the larger women’s group.

The Verdict: This is Garlic Bread

I’ve made this spread twice now, but my research into other recipes for garlic butters and spreadable toppings has inspired me to experiment. When I make it again in the future for my garlic-loving family, I’m going to replace the garlic salt with garlic powder and with grated or minced garlic cloves.

What a fantastic recipe—warm, gooey, garlicky perfection; a contributor crediting a source; and a mysterious eponym! Another chef’s kiss seems warranted.

I love these recipes that leave trails of breadcrumbs.

Contributor

I provided a biography for Pat Buen in a previous post, “Krystal’s Dishes,” but I’ve included it again here for readers’ convenience. Here’s the link to that post: https://blog.cord.edu/karlaknutson/2023/07/17/krystals-dishes/

Pat (Patricia) Buen was born in Louisiana, in 1943, to Captain Herbert and Laura Wilson, but it seems they ventured north, as she grew up and went to high school in Berthold, ND (northwest of Minot). In 1961, she married Gene Buen, also from Berthold, and they briefly lived in Minot, where Pat worked at First National Bank, before moving to Velva in 1964. Mr. Buen (funny how the honorific still can be present for us even decades after being in their classroom 😊) taught math and coached baseball in Velva for more than thirty-five years. Pat and Gene had three children, Dianna, Daniel, and David, and after staying home with them during their childhoods, Pat returned to working in banking in Velva for twenty-five years, retiring in 2013. Both Buens were active at Oak Valley: Gene served on the council, and Pat served as church secretary for thirteen years, as well as in circles and the Sunday school program. I understand that Pat traveled to most of Gene’s baseball games during his long tenure as a coach, traveling with the team all over ND and in particular, to their 16 appearances at the state baseball tournament; Velva won three championships—in 1984, 1986, and 2010. Gene passed away in 2015; Pat in 2018. I know Pat for a variety of reasons: church activities, my mother’s homemaker’s group, and her family: she is my friend David’s mother and Mr. Buen’s wife (and he was my math teacher for most of high school).

Pat’s other contributions to the cookbook are “Grouse or Pheasant at its Best,” “Sticky Muffins,” “Snicker Cake,” “Freezer Strawberry-Rhubarb Preserves,” “Brunch Egg Scramble” (see https://blog.cord.edu/karlaknutson/2023/10/25/brunch-egg-scramble/), “Upside-Down Pizza,” “No-Cook Peach Cream Pie,” “Strawberry Pie,” “Peach Pie,” and “Hot Sandwiches.” So many of these have amazing names, which reminds me of Pat. She was fun to be around and an excellent cook. During my interviews in Velva, I heard many people speak of how often they made Pat’s recipes from this cookbook; her French bread was singled out as a favorite. It’s now one of mine too.

This post is part of an ongoing series in which I make and reflect on recipes and the people who contributed them to the 1985 Oak Valley Lutheran Church compiled cookbook, The Joy of Sharing.