As I noted in the introduction to my Movie Night Recipe series (https://blog.cord.edu/karlaknutson/2024/05/22/a-prelude-to-movie-night/), the main event of our Puss in Boots movie night was lasagna, the quintessential Italian-American dish of ooey-gooey baked cheesy pasta, beloved of orange cats everywhere. Or at least of the orange cat on Saturday morning cartoons when I was a kid and now in three feature-length films.

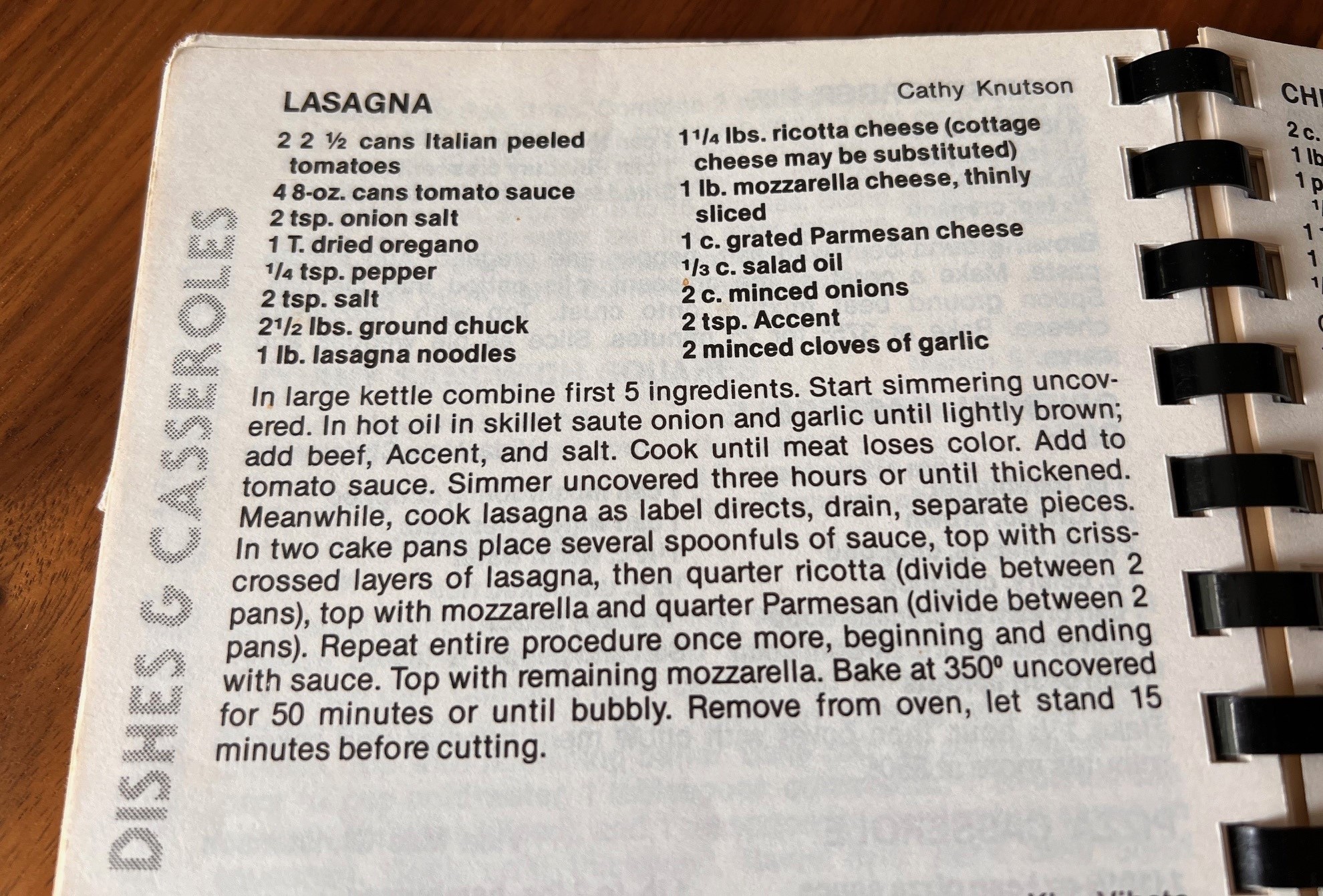

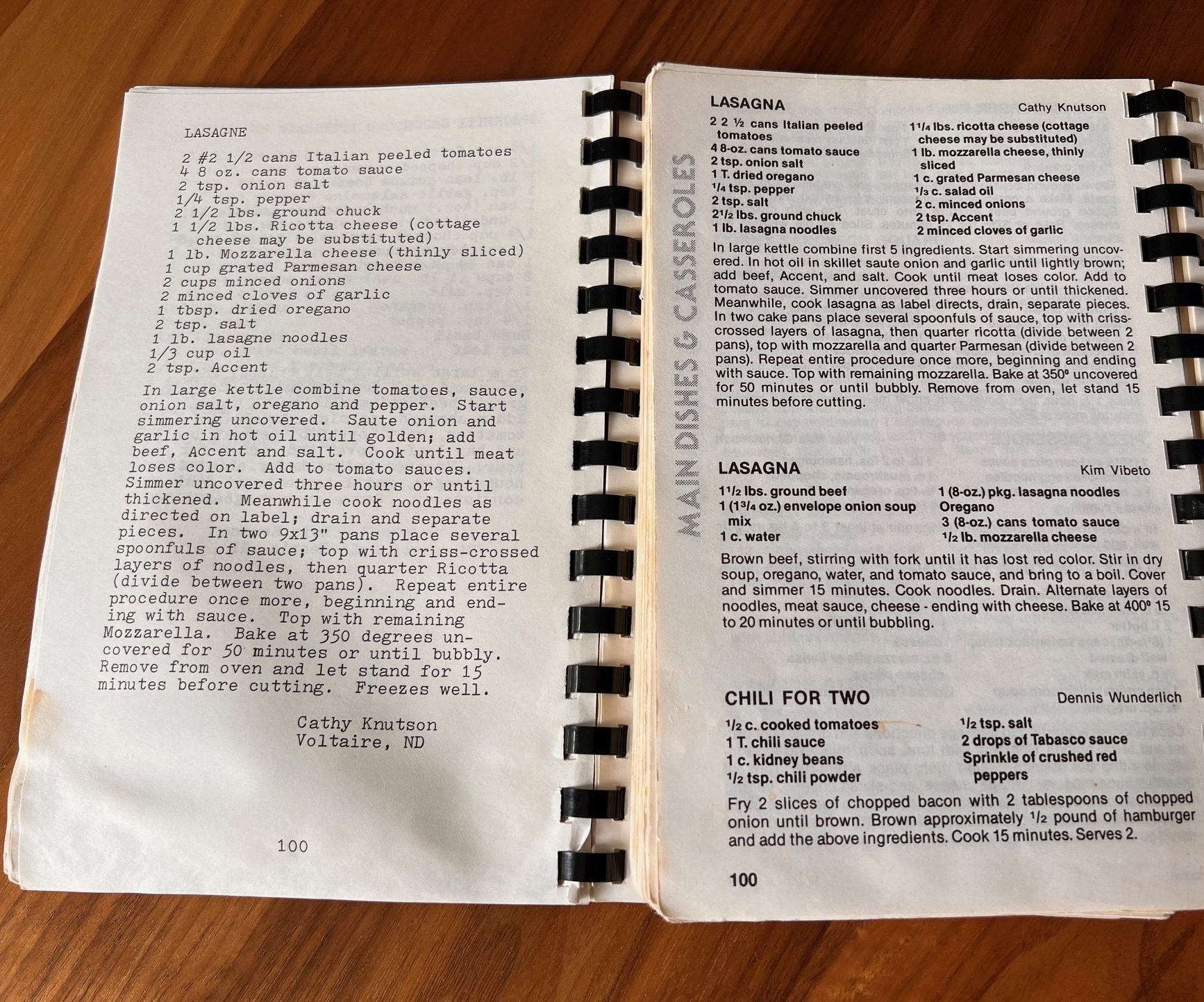

The Joy of Sharing includes four recipes for lasagna in its “Main Dishes & Casseroles” section: 1) “Slim & Trim Tuna Lasagne” contributed by Irene Grunseth (which I know will not be enjoyed by my dining companions but is a fascinating record of the physical monitoring of women’s bodies occurring in 1985 in central North Dakota); 2) what appears to be a quick version of the dish contributed by Kim Vibeto; 3) another submitted by Linda Hystad, with classic lasagna ingredients but a short cooking time; and 4) “Lasagna” contributed by Cathy Knutson. In space on the page, number of ingredients, and preparation time, Cathy’s wins for being the longest.

And while Cathy Knutson may never live down the microwaved-liver slices (for the backstory, see “Church Cookbooks and Women’s Lives in Mid-Twentieth-Century Central North Dakota: An Introduction” at https://blog.cord.edu/karlaknutson/2023/06/12/opening-gambit/), her lasagna recipe is fantastic—she received this recipe from a friend at a church potluck while in college in Illinois (the university Lutheran church was called Uni-Lu—wow). I remember begging my mom to make it over vacation breaks during college. Now making it for myself years later, I remain impressed by this recipe and its ability to inspire zany, lasagna-fueled cattitude.

An All-Day Affair

This is a recipe you make when you have some leisure time, and that’s really how I have always approached cooking. I do not like to feel rushed and enjoy cooking when I am able to devote time to it; so I want to do it mainly on weekends. It’s too bad we need to eat on weeknights too.

The recipe’s instructions specify two processes: first, simmering the tomatoes, tomato sauce, and seasoning in a large pot, and then sauteing onion, garlic, and browning beef, though the recipe uses this fascinating, unappetizing phrase: “Cook until meat loses color.” Okay…what? What color? Pink? How is brown not a color? What am I missing, Mom?

All of these items are added to the tomato-based sauce, and simmer for about three hours until thickened.

Toward the end of this period, I took the liberty of adding fresh basil from my patio to the sauce. You do need to plan ahead, as well as prepare the lasagna noodles prior to the end of the simmering period.

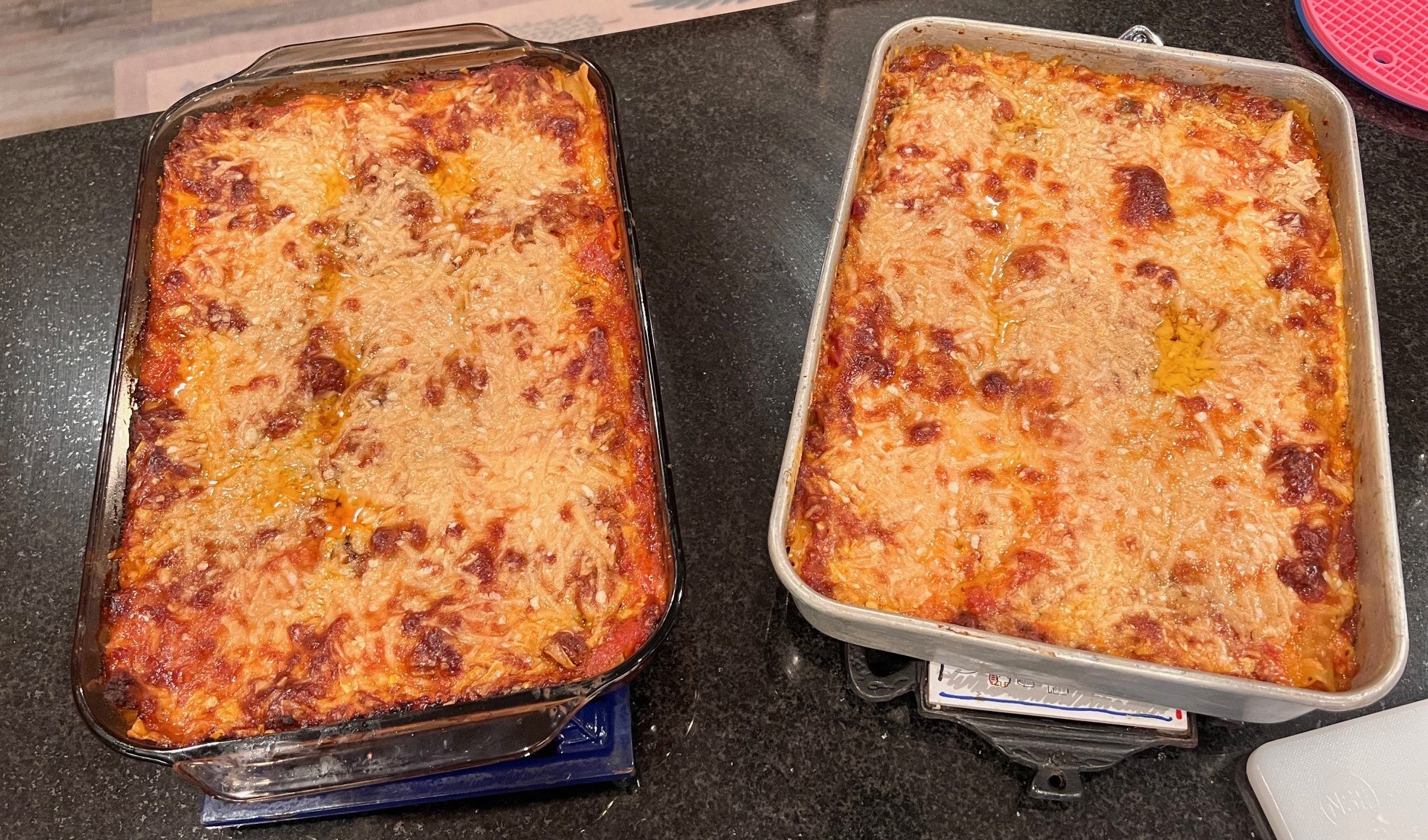

The assembly also took some time, as it’s a big recipe, making two 13 x 9 inch pans of lasagna. Layering the lasagna noodles quickly enough that they don’t stick together, as well as adding sauce and the multiple types of the three cheeses—ricotta, mozzarella, and Parmesan—is a serious endeavor, and I forgot the order at first and ended up with noodles in the top layer. But I added more cheese to cover it, and it was just fine.

I actually used way more cheese than was prescribed, about one and a half to two times more than the recipe calls for. But I stand by my decision. Who wants tough baked pasta? More cheese is not just more in a lasagna. More cheese is better, I think.

After 50 minutes in the oven at 350 degrees, resting for 15 minutes after baking, and dishing it onto our plates with sides of “Sharon’s French Bread” and “Simply Dilly Cukes,” we were finally ready to feast like Garfield.

Reflections

And we were not disappointed. The lasagna was delicious! Since the sauce simmered for such a long time, it was rich and flavorful, and the basil, onion, garlic, and dried oregano added extra depth to the sauce. Everyone had seconds, and there were no complaints, nor recommendations. We went to bed happy, full, and courageous, thanks to our orange feline companion Puss in Boots.

I made this recipe again in January, a couple weeks before giving a Concordia College Centennial Lecture about this project. We ate one pan, and I froze the other, defrosting it in time to reheat and serve at the lecture as one of the sample dishes from The Joy of Sharing. As I came home with an empty pan, it seemed to be well-received that evening too.

Questions

As I made the lasagna, I did have a few questions about the nature of the recipe.

For example, some ingredients gave me pause. The first ingredient on the list, “2 2 1/2 cans Italian peeled tomatoes,” caused me a bit of consternation. I know this is a big recipe, making two 13×9 inch pans of lasagna, but I didn’t think it really needed 22.5 cans of tomatoes. I’m being a bit cheeky, of course—I knew cans were labeled with numbers sometimes, but I certainly did not know why. Writing for The Spruce Eats, Peggy Trowbridge Filippone explains that the National Canners Association created this numerical system for labeling cans according to diameter and height. She also notes that the 2 ½ can appeared later, after the number 2 and 3 were found to be cumbersome sizes for the vegetables and fruits they held, leaving too many leftovers (https://www.thespruceeats.com/can-sizes-for-recipes-4077057). I imagine this organization did not realize part of their legacy would be consternation over typographical conundrums for the organizers of community cookbooks.

Another fascinating ingredient is Accent, which I had to look up online while standing in the seasoning section of the grocery store. Ac’cent, with the apostrophe included (which is not in the recipe) is an apt moniker for this “flavor enhancer,” which claims it “Wakes Up Food Flavor!” And it’s designed to do just that—to create umami through a substance made from corn called monosodium glutamate (https://accentflavor.com/about/).

Yes, that’s MSG—developed in 1907, by Japanese chemist Kikunae Ikeda, this broadly condemned ingredient caused fear for decades. The fear was the result of a never-proven suspicion (not actual scholarship—a suspicion!) of an American doctor in 1968; instead, he wrote a letter to a medical journal, blaming MSG for various symptoms of what he called “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome” (Wong, https://www.cnn.com/travel/article/msg-changing-views-cmd/index.html). This legacy makes the National Canners Association’s 2 ½ can debacle seem very charming.

However, the doctor’s xenophobic, collective condemnation of Chinese cuisine, MSG, and sodium has never been confirmed after decades of research, and MSG has had a resurgence in popularity in the past few years, thanks in part to celebrity chefs, such as David Chang, who is also championing microwave cooking (for more of this history see J. Kenji López-Alt’s deep dive into the research, https://www.seriouseats.com/ask-the-food-lab-the-truth-about-msg; Michael George, https://www.cbsnews.com/news/tim-ma-msg-unhealthy/; Wong above, and The Oxford Companion to Food, among others). Chang and others draw upon MSG to make certain foods taste better; as The Oxford Companion to Food explains, “it seems to make the tongue, and to a lesser extent the palate, more receptive to savoury, salty tastes.”

In Cathy’s lasagna dish, the two teaspoons of Ac’cent were added to the beef, along with two teaspoons of salt, at a typical time—during the browning process, adding to its savory, meaty flavor. Ground chuck, the type of ground beef specified by this recipe, also contributes to a rich beef flavor. As Martha Stewart explains, “chuck is one of the eight primal cuts of beef. It comes from the shoulder area of the cow, a section of hard-working muscles that are tough, but also rich in collagen, marbled with fat, and full of flavor.” So chuck is a cut that will give your dish what Meathead Goldwyn refers to as “great beefy flavor” in Meathead: The Science of Great Barbecue and Grilling (268).

But ground chuck was nowhere to be found in the meat case at my local supermarket, and so I returned to Meathead for advice. To procure good great chuck, Meathead says, “the easiest thing to do is to pick a nice-looking USDA Choice-grade chuck steak, ask the butcher to grind it, and add more white fat if needed to get the blend up to 20 to 30 percent” (268). Unfortunately, Hornbacher’s would not grind a chuck roast for me. They just don’t do that, they said.

I settled for 75/25 ground beef, but next time I will visit specialty butcher shops until I get freshly ground chuck. Why? Other than for the satisfaction of getting the recipe’s specified ingredient? Because that great beefy flavor, as Meathead clarifies, comes from the quality of the cut and from the amount of fat. Chuck is a good cut of beef with a nice amount of natural fat, which, Samin Nosrat explains in Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat: Mastering the Elements of Good Cooking, creates a taste that is “beefier” than leaner cuts (69). Nosrat further elaborates on how this beefy taste develops: “As a well-marbled steak cooks, the fat will melt, making the meat juicier from within. And since fat carries flavor, many of the chemical compounds that make any one kind of meat taste like itself (beef like beef, pork like pork, chicken like chicken) are more concentrated in fat than in lean muscle” (71).

So there you have it—why Meathead notes that 25 to 30 percent fat is what “top chefs” use in their burgers (268). Unsurprisingly, this amount of fat does create ample grease during the browning process, and it made me wonder whether I should drain it or not (without an indication in the recipe), given how important fat is to the flavor. I compromised, draining some but not all. I’m sure both of my grandmothers would have been horrified, as committed as they were to the 90 or 95 percent lean ground beef they insisted on purchasing. Bodily discipline for weight management as well as health concerns triumphed over flavor for these women and many others during the 1980s.

While I said a great deal about the delightful creation of melty cheese in my post about the cheesy garlic bread I made to accompany this lasagna in Movie Night Recipe #1, (https://blog.cord.edu/karlaknutson/2024/05/22/sharons-french-bread-movie-night-recipe-1/), I do want to note one more exciting detail about cheese here, since the melty string of cheese stretching out from a forkful of lasagna is one of the dishes’ stock images.

What’s particularly wonderful about lasagna is the combination of different types of cheeses, all of which provide unique textures and flavors. Mozzarella and Parmesan are both melting cheeses, but as they differ in moisture, so too does their melting behavior —the moisture in mozzarella means it melts together and the harder, drier Parmesan melts but not into a gooey mess, as Harold McGee asserts in On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen (64). And ricotta doesn’t melt at all! McGee explains that this is the result of being curdled with acid instead of rennet (64), which leads to the water content evaporating when ricotta is heated (65). So the three classic cheeses in lasagna offer a plethora of textures and flavors, all in the same bite.

One final puzzlement—is this dish spelled “lasagna” or “lasagne”? It has an “a” in The Joy of Sharing, but when this recipe previously appeared in another community cookbook, a Knutson/Frantsen family cookbook compiled by Lois Knutson called The A-B-C’s of Cooking, released in December of 1982, it was titled “Lasagne.” Is it a typo? Did Cathy change her mind? Or did an editor step in during the compilation of one of these two cookbooks?

The discrepancy has to do with the history of lasagna. In the fascinating book, Red Sauce: How Italian Food Became American, Ian Macallen traces the history of this dish from Europe and notes it was already “an American household staple in the 1960s” (121). Lasagna with an “a” denotes the type of noodle (which should be fresh, not dried), which is “directly related to the Roman lagana, also sheets of flattened dough” (121), and is the origin of other flat and shapable noodles, like tagliatelle and fettucine (122). In ancient Rome, lagana also typically were cooked by liquid while baking, and continued to be prepared this way through the Middle Ages, at which time the dish resembling modern lasagna first appeared (Macallen 122).

Now to our spelling query: “lasagne” is the plural of these flat noodles, used in the northern part of Italy, and “lasagna” is the singular and the preferred usage in southern Italy; in the US, “lasagna” became the conventional term for the dish because most Italian Americans are from the south (Macallen 122). Wild, right? So when a recipe titled “Lasagne” hit the Knutsons, Frantsens, and other extended family in 1982 or the readers of Irma S. Rombauer’s American classic The Joy of Cooking, the recipe’s title refers to the many noodles in the dish, similar to when we say we are having spaghetti and meatballs for supper. “Lasagna” indicates the one pan dish or the individual lasagna noodles constituting it. Macallen’s chapter title is a helpful reminder: “One Lasagna, Many Lasagne.”

Or “I have brought a dish of lasagna full of lasagne.”

That sentence is less helpful if only spoken, since the pronunciation of the two forms is the same. I imagine some folks have assumed “lasagna” is a spelling and pronunciation mistake—a misattribution of a terminal “a” because the “e” was pronounced with a schwa sound.

Fascinating! And it always comes back to grammar and language history, doesn’t it? They’re the best.

Contributor: Cathy Knutson

Cathy (Christensen) Knutson was born near the end of 1952, the second daughter of Carlyle Christensen and Helen (Stusrud) Christensen, of Minot, North Dakota. Prior to moving to Minot in 1954, the family, including Cathy’s older sister Karen, lived in Bowbells, ND. Cathy attended Minot Model and Minot High School before matriculating at Minot State College (now University) and transferring to Northern State University in Dekalb, Illinois, from which she graduated with a Bachelor of Science in elementary education in 1974. While teaching elementary school in Karlsruhe, ND, she returned to Dekalb for graduate coursework in special education during the summers of 1975 and 1976.

Late one Friday afternoon in April, 1976, Cathy Christensen met Kristian Knutson on the Sawyer hill on Highway 52, when he stopped to help her change a flat tire. The son of Martha (Frantsen) and Irvin Knutson of Velva, Kristie Knutson grew up in rural Voltaire and Velva, attended the University of North Dakota and North Dakota State University, and served in the army (stationed primarily in Frankfurt, Germany, which allowed him to see most of Europe during leaves). In 1967, Kristie purchased the land in Olivia Township originally homesteaded by his great-uncle Christian I. Knutson, beginning his fifty-year farming career. Cathy and Kris married in December of 1976, and Cathy joined Kristie on what was now their farm, where they raised two daughters, Karla and Corene.

Cathy taught elementary grades at area schools, and after earning her master’s degree in special education from Minot State University, taught in this field for the remainder of her career, including the last seventeen years at Minot High School—Magic City Campus. During this period, Cathy was active in the Velva community, as a Velva Music Mother, a judge at regional high school speech tournaments, a member of groups like Velva Homemakers Club and La Leche League. She was an active member of Oak Valley Lutheran Church as well, serving on the church council, as well as an officer in WELC, Circle, Altar Guild, on the Education and Worship Committees, and as the Treasurer of the Four Point Parish. She also taught Sunday school and confirmation classes.

Cathy and Kris retired to Fargo, ND, where they remain busy—attending theater productions, lectures, and writer’s readings, a wide variety of high school and college sporting events, and concerts. They recently traveled to Winnipeg, Manitoba; Madison, Wisconsin; and Bemidji and St. Paul, Minnesota to see various bands (The Mavericks and the Eagles are favorites), to Banff and Glacier National Park, and to Illinois to visit relatives and have fun in Chicago. When they actually are home, Cathy attends multiple book club meetings each month and was recently elected to her new church council in Fargo. They’ve both made a lot of friends and enjoy going out to dinner with friends and with their daughters’ families.

The Knutsons also spend quality time playing with and transporting their three grandchildren, as well as attending the kids’ dance performances and games and chauffeuring them to rehearsals and practices. In December of this year, the couple will celebrate their forty-eighth wedding anniversary. Bill Self and Andrea Hudy—their two cats named for the coach and former physical trainer of their beloved Kansas Jayhawks men’s basketball team—are very proud of them.

Cathy’s other contributions to The Joy of Sharing include the now infamous “Liver Slices,” “Caramel Cookies,” “Graham Cracker Bars,” and “Baked Eggs.”

This post is part of an ongoing series in which I make and reflect on recipes and the people who contributed them to the 1985 Oak Valley Lutheran Church compiled cookbook, The Joy of Sharing.