Early this summer I made two baked goods with rhubarb, my favorite “vegetable that often masquerades as a fruit” (McGee 367). As I explained when writing about last summer’s rhubarb recipes—a pie and a crunch (https://blog.cord.edu/karlaknutson/2023/07/15/243/ and https://blog.cord.edu/karlaknutson/2023/06/27/rhubarb-pie/), I love rhubarb—its tartness, its color, its juiciness—really, I love anything and everything about it.

My July 2024 column for the Fargo Forum, Vintage Dishes, featured a fantastic rhubarb cake that is easily the best cake I’ve ever made: https://www.inforum.com/lifestyle/the-best-cake-ive-ever-made.

This assertion is supported by my family—my daughter and her friend loved it during a playdate, though they thought it was very filling, and my husband ate most of it while my daughter and I were in Boston for a conference. And he does not eat things he does not think taste good.

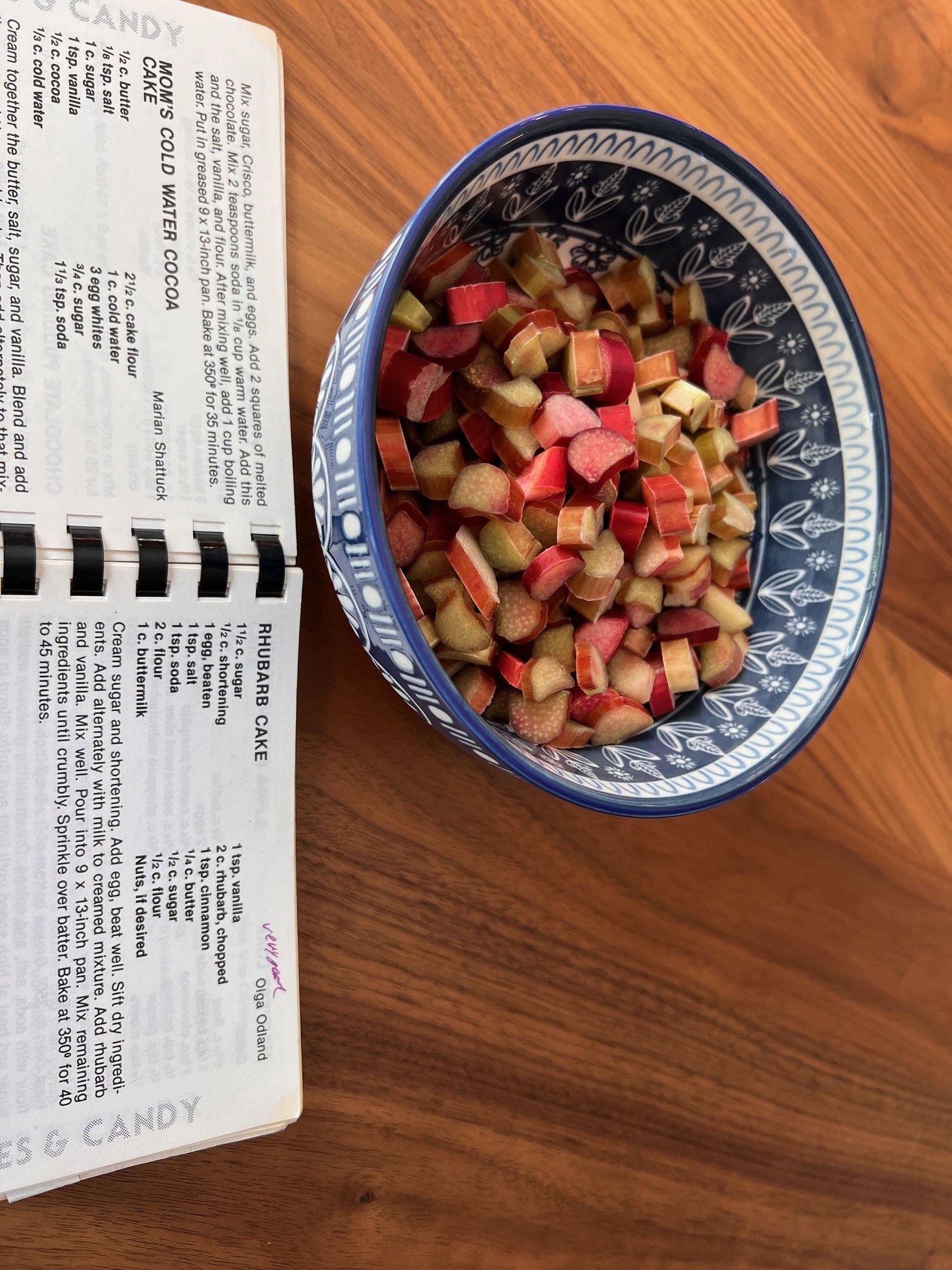

Rhubarb Cake Photo Essay

Contributor: Olga Odland

Born Olga Lovro, February 15, 1928, to Hans and Oline Lovro, both immigrants from Norway, who farmed near Bonetrail, ND, which is close to Grenora, northwest of Williston. At age nine, the family moved to farm near Granville, ND, in McHenry County, north of Velva, where Olga graduated from high school and moved to Minot to work at Union National Bank. After marrying Ingvald Odland, born January 4, 1926, to John and Otilie Odland, of Velva, Olga and Ingvald moved to his family farm in Hendrickson Township in 1947, where they raised three children: Nancy, Mary Lou, and John. Olga passed in 2018; Ingvald in 2021. Olga submitted three recipes to The Joy of Sharing, the aforementioned fantastic rhubarb cake, “Brown Graham Bread,” and “Holiday Orange Salad.”

A Good Crumb

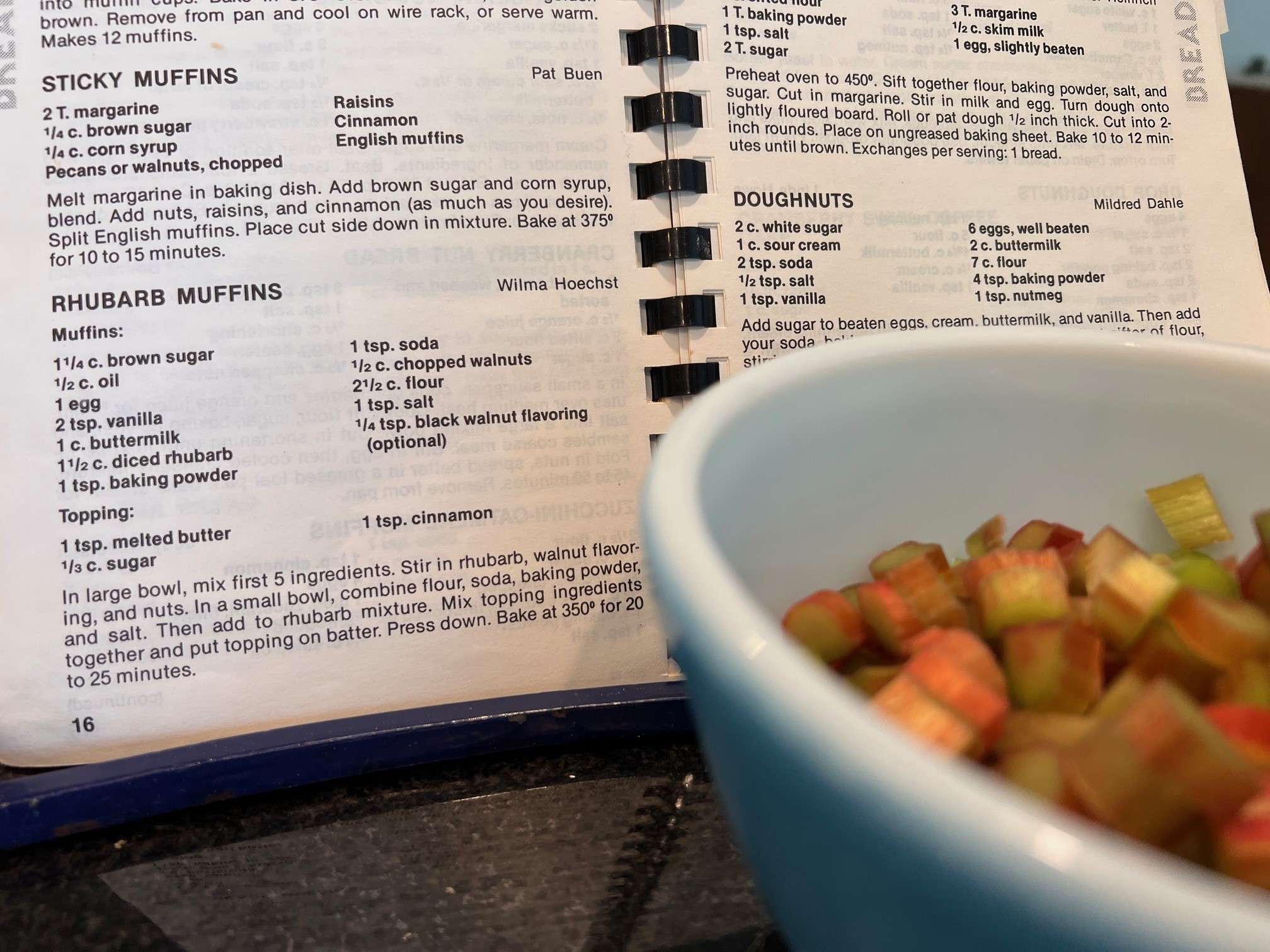

My Fargo Forum column explored why that cake was so good, and “Rhubarb Muffins,” by Wilma Hoechst, the other rhubarb treat I made during the early summer’s rhubarb season, was good for the same reasons!

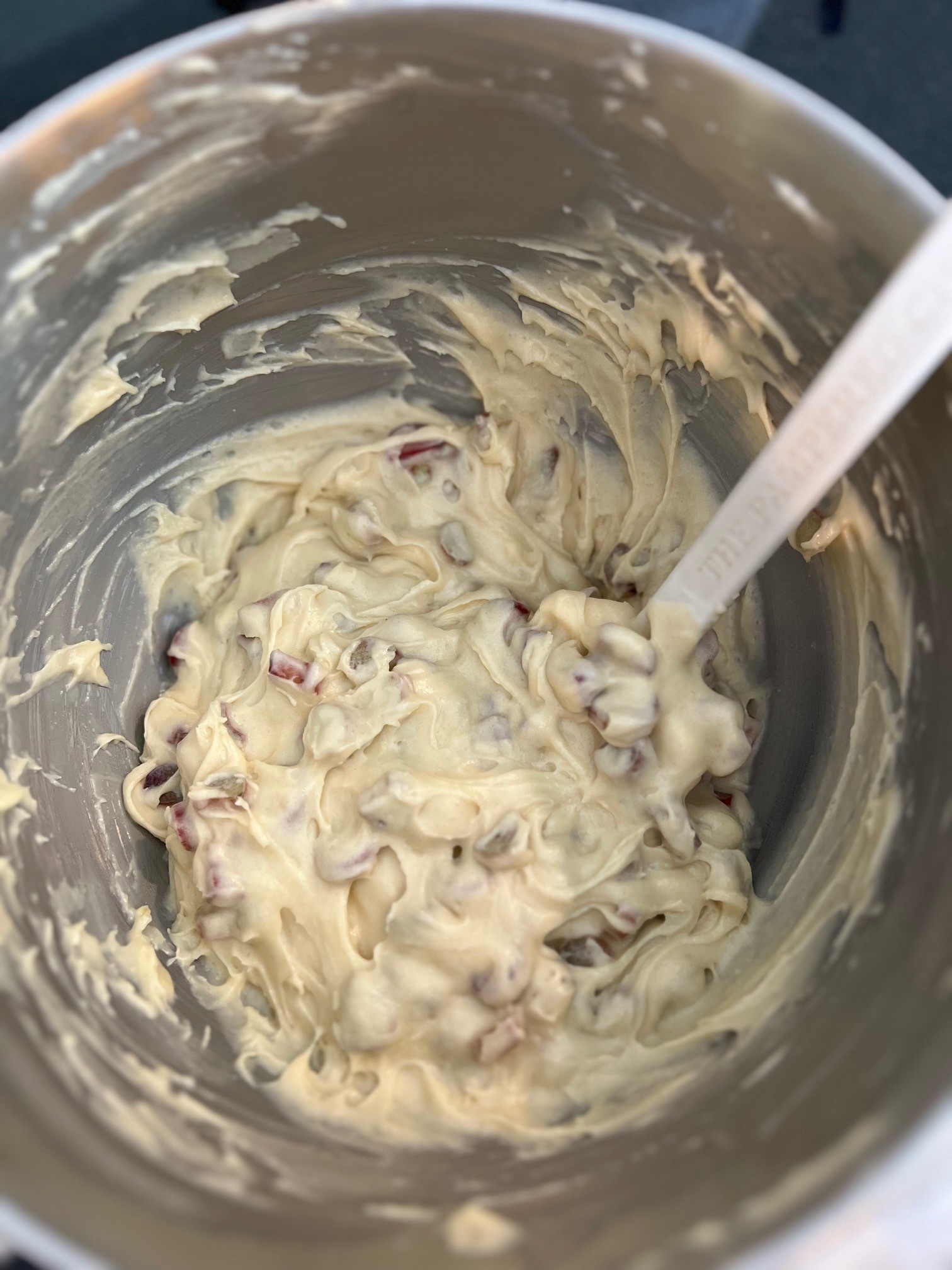

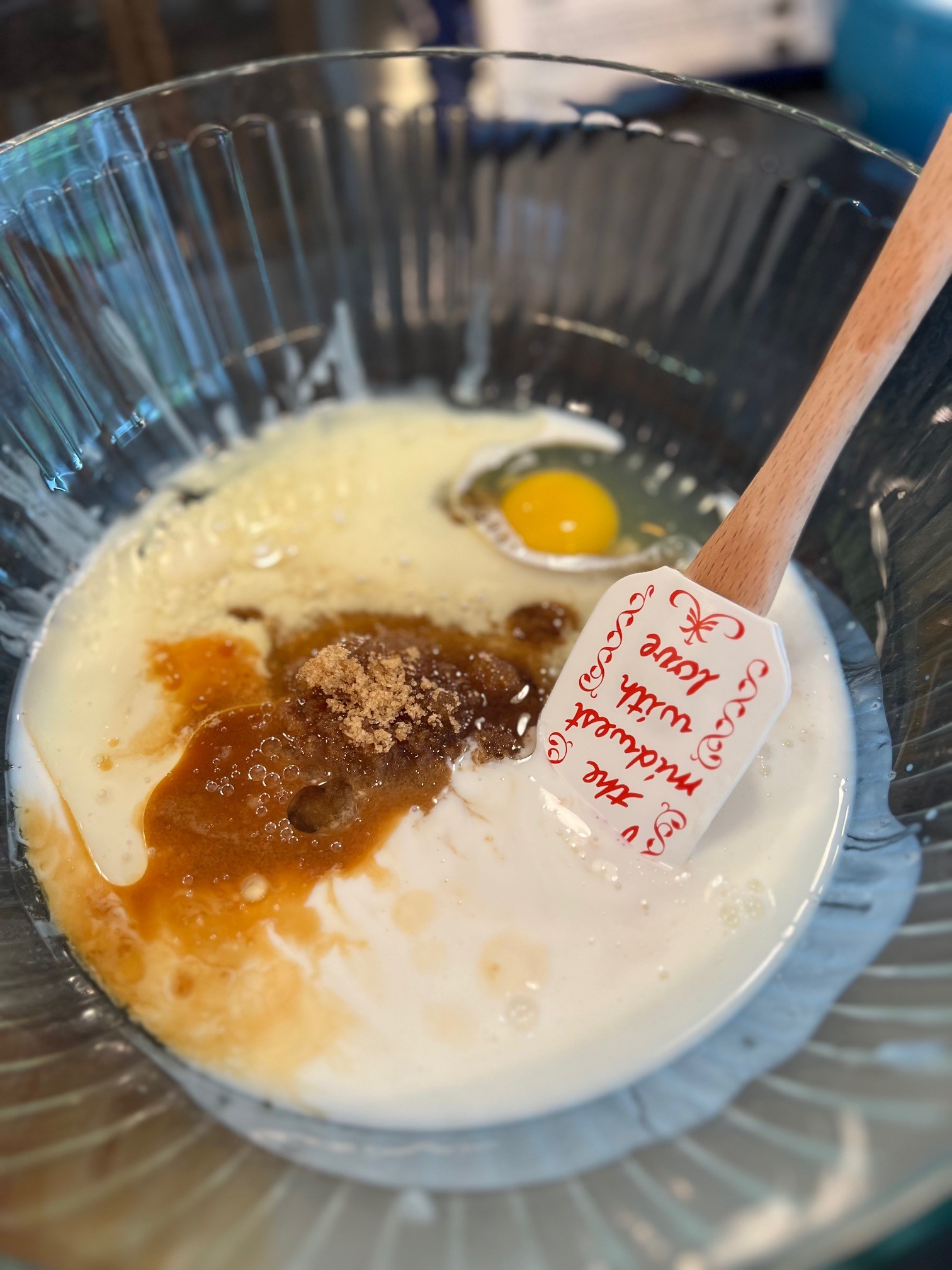

Both baked goods were moist and had excellent flavor and texture. For example, they both had a good crumb; the recipes ensured the right texture through creating aeration by creaming the sugar and fat (I used butter instead of shortening in the cake and the specified oil in the muffins), stirring only until just mixed, and using buttermilk.

As James Beard explains in American Cookery, buttermilk creates a tender consistency: “using acid, such as sour milk, buttermilk, or citrus juice, helps to break down the gluten, which is why pioneer cake bakers, especially in the Midwest, preferred sour milk cakes” (646). For more about this scientific reaction, see Harold McGee’s exploration of how this happens in my post about pancakes: https://blog.cord.edu/karlaknutson/2023/08/11/grandmas-pancakes/.

Easy and Swift

This was a straightforward recipe with some fun variations on my expectations. For example, the baker is supposed to fold in the chunky ingredients—the rhubarb and nuts—to the wet ingredients prior to adding the dry ingredients—here again the typical flour, baking soda and powder, and salt.

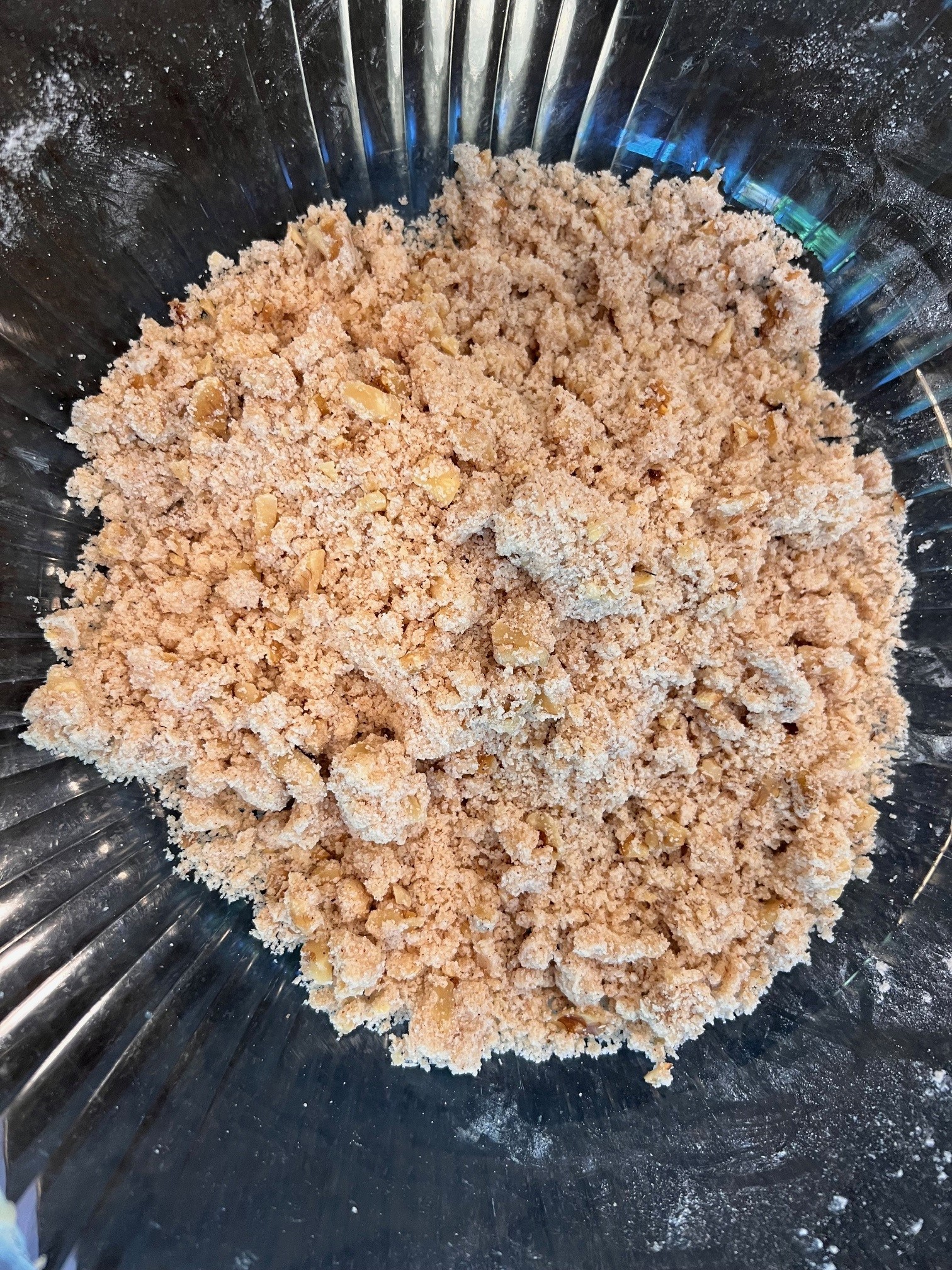

Like other rhubarb desserts—including Odland’s rhubarb cake, these muffins have a crumbly, sugary topping of melted butter, sugar, and cinnamon. The baker is instructed to sprinkle the topping and then “press down,” which made me very worried, as I was concerned that I would press too firmly and make the topping more of a “mix-in.”

Following the instructions, I placed the 24 muffins in my oven at 350 degrees, yet set the timer for only ten minutes. At that point, I switched the muffin tins around to be on different sides of the oven, as well as rotating them front to back. After another ten minutes, a toothpick came out clean, and when it did, I removed them to cool on a rack. Hoechst mentions that they may take an additional five minutes, but mine didn’t, which reinforces the importance of relying on multiple tests for doneness—internal temperature, shrinking from the sides, color, and responding to a touch—not merely a recipe’s prescribed cooking time.

Rhubarb’s Regality

Much like the cake, these muffins were fantastic—tender and soft, with an open crumb, bright and tart thanks to the rhubarb and crystalized sugar topping, and moist, again thanks to the rhubarb.

Watching The British Baking Show this summer with my daughter, I learned that the British call a fresh-fruit cake a “fruity cake.” And as bakers know, a primary challenge when baking with fresh fruit is dealing with the liquid it releases, lest you discover a soggy bottom or streaks of raspberry or blueberry across your scones.

Rhubarb is one of the quintessential moist ingredients in fruity cakes and desserts—in fact, it is known as the “pie plant.” A herald of spring, rhubarb is one of the first “fruits” available as cold climates shift to the warmer seasons, and it remains particularly popular in many of those locations, where you can see it growing in gardens, landscaping, and farmsteads. IF you don’t have a rhubarb plant, you’re often wondering where you can acquire this ingredient. I’ve planted one, but since it takes two or three seasons to mature, I had to rely on my favorite farmer’s market and on my father’s friends. A hearty thank you to them!

After noting that it originated in Asia, McGee provides a chronological history of its many uses, including as a cathartic (laxative or purgative) in Chinese medicine, in vegetable stews in Iran and Afghanistan, with potatoes in Poland, and as the basis of sweet pies and tarts in England starting in the eighteenth century (367). As production became more sophisticated and efficient and sugar dropped in price, rhubarb flourished in the twentieth century, with a boom between the two world wars (McGee 267). Both Odland and Hoechst undoubtedly were baking up a storm during this boom, married and raising children on their farms.

Laxative, sweet treat, savory ingredient. Rhubarb is versatile, certainly. And delicious, when buoyed by ample sugar and fat.

Baking as Experiment

Watching the delightful The Great British Baking Show is both a fun family activity and useful for my project working through my grandmother’s copy of The Joy of Sharing. It’s a productive method of research, valuable not only for offering visual and oral depictions of baking techniques about which I’ve been reading but also for illustrating how baking and cooking are processes of trial and error, infinitely variable. Research, experience, technique, tools, ingredients and environments can change the outcome of a recipe, even for seasoned bakers. For me, and it seems, for many of the show’s contestants, a disappointing outcome is hard to shake off. I’ve never been a confident cook, and so I assume it’s my fault—my lack of expertise or attention—when a dish doesn’t come out as planned. In fact, I made this cake twice, and the second time it wasn’t as good; I blame it on using rhubarb that had been picked a few days earlier. But these bakers are incredible, and I appreciate that the show depicts their triumphs and their failures, frequently accompanied by their consternation—what they had planned in practice and executed brilliantly at that time did not come out brilliantly in the tent. When you start to think about the all the variables at play every time you make any recipe, it’s almost enough to make you throw up your hands and eat out for the rest of your life.

But that’s not really possible, is it? Nor very fun.

Contributor: Wilma Hoechst

Wilma Heilmann was born on July 12, 1909, on the land her parents—Fred and Emile Wutzk Heilmann—homesteaded south of Sawyer, north of Velva. In 1928, her family moved to a farm southeast of Velva, and in 1933, she married Erich Hoechst and moved to his parents’ farm near Bergen, a small community southeast of Velva on what is now Highway 52. Prior to purchasing the farm in 1915 and moving onto it in 1919, William and Minnie Hoechst lived in Minnesota Lake, MN, where their fourth child Erich was born on July 2, 1900. Erich and Wilma farmed and raised both cattle and three daughters, Maryln, Lois, and Joyce. After retiring in 1965, they moved into Velva in 1976; Erich passed away that same year, and Wilma lived in Velva until she passed in July 1997.

I’m guessing Wilma or at least someone in her family liked rhubarb as much as I do, because she contributed two rhubarb recipes to The Joy of Sharing: the aforementioned muffins, as well as “Rhubarb-Mallow Dessert,” “Raisin Caramel Pie” (is that a common combo I don’t know about?), and “Deluxe Hash Browns.”

Yum…I think I’ll go whip up a batch of rhubarb muffins right now. I knew all that chopping would pay off; there’s rhubarb aplenty in my freezer this fall. Lucky us!

And lucky you too, if you try either of these recipes.

This post is part of an ongoing series in which I make and reflect on recipes and the people who contributed them to the 1985 Oak Valley Lutheran Church compiled cookbook, The Joy of Sharing.