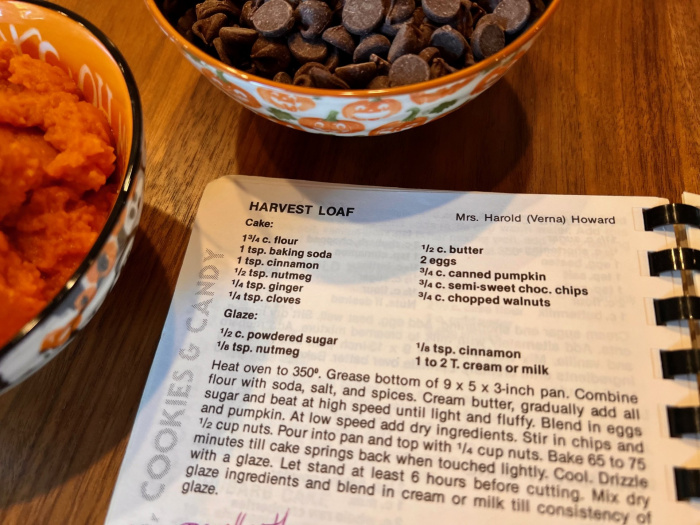

As the leaves changed colors and the weather turned chilly enough to wear sweatshirts, then sweaters, and finally, coats, I looked for autumnal recipes in The Joy of Sharing. One of these adventures appeared to be quintessential fall: Harvest Loaf,” contributed by Mrs. Harold (Verna) Howard, as she is listed. A harvest loaf sounds like a seeded bread to me—raising images of pumpkin seeds and sunflower seeds in a chewy, savory bread—but it’s actually a pumpkin loaf cake, located in the “Cakes, Cookies, & Candy” section following the fruity cake recipes. This recipe opens a two-page spread in the cookbook featuring the bounty of fall—spice and apple cakes.

Truly, an Adventure

This recipe is the first one I’ve encountered with a glaring mistake. It has a beautiful visual format—with colons and spaces clearly demarcating the ingredients to use for the two parts of this recipe, the cake and its glaze. And everything goes well, until the fourth sentence, when the reader is instructed to cream butter with sugar.

“What sugar is this?” asks the baker. Did I miss getting the sugar out of the cupboard when I read the ingredient list to prepare my mise en place?

Alas, it was not I who was missing an ingredient, but the recipe itself.

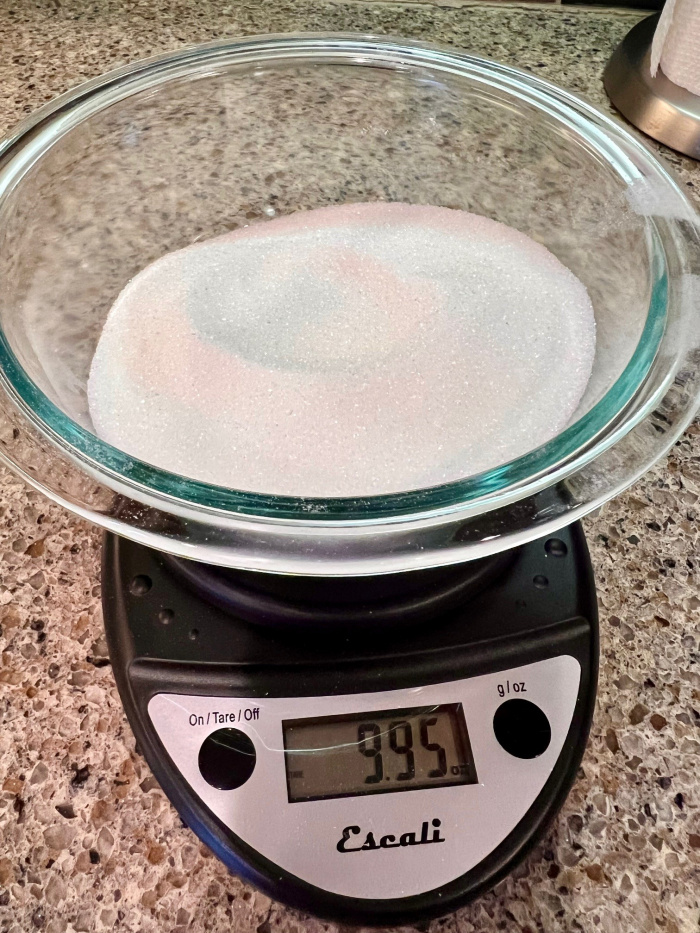

Since it seemed clear that sugar was necessary, I turned to the internet, searching for what amount of sugar to use in a cake recipe with 1.75 cups of flour. I learned that sugar in a cake should be equal to its flour in weight, and so I used my trusty kitchen scale to weigh the flour first, and then scooped sugar onto the scale until it reached the same weight of 9.95 ounces.

This amount equaled 1.25 cups of sugar, which I did then add to the creamed butter for more creaming on high until the mixture became “light and fluffy.”

Next came the eggs, one at a time, then the three-quarters of a cup of canned pumpkin, prior to the dry ingredients, which I’d previously sifted together.

Just like when making chocolate chip cookies or fruity cakes, I removed the bowl from my mixer and folded in the chocolate chips and chopped walnuts by hand.

Though the recipe didn’t specify to do so, I did grease the loaf pan with baking spray, which is recommended for butter cakes by Irma S. Rombauer’s Joy of Sharing, after which I followed the instructions to top the loaf with the reserved nuts.

I placed the cake in the oven at 350˚, and since I was using a stoneware loaf pan, I checked the temperature after 30 minutes. It had reached 135˚at that point; 145˚at 50 minutes, and 190˚ at 75 minutes, which was the top of the 65- to 75-minute range recommended in the recipe. Though I knew a cake needed to reach 200˚ and shouldn’t venture over 210˚, I let the stone pan finish the baking outside the oven, which it quickly did.

Being able to check internal temperatures with my Thermapen is still one of my favorite things about modern baking and cooking. Relying on accurate temperature readings has opened up a world of certainty that other, more expertise-based methods did not offer. Howard herself recommends another classic tip, baking “till cake springs back when touched lightly.” However, I love the reassurance of seeing my thermometer probe emerge cleanly—like in the recommended toothpick trick. Other morsels of advice were to see if the sides of the cake retract from the edges of the pan, as well as to knock on a loaf of bread to see if it sounds hollow. What fun!

Since the recipe indicated the loaf should rest for six hours, I let it sit and returned to mix the glaze much later.

As I prepared the glaze, I noticed another error, this time of sequence. After the instruction to cool the cake, the next sentences appear out of order: “Cool. Drizzle with a glaze. Let stand at least 6 hours before cutting. Mix dry glaze ingredients and blend in cream or milk till consistency of glaze.” Of course, “Drizzle with a glaze” should be the last sentence of the paragraph, the final preparation prior to serving. But it’s almost like an instruction for what is going to happen in the future with the glaze. If so, then for clarity of comprehension, I would expect it to introduce the direction opening with “mix dry….” and to connect the two sentences with a colon, to make the heading-status absolutely clear. So again, reading an entire recipe and making a plan ahead of time is essential for the user.

With the glaze on, I sliced two pieces for my daughter and me, and we sat down to try “Harvest Loaf.” Despite the chocolate chips, she wasn’t enthusiastic, and I could see why. It was a bit dense and dry, and the nuts on top were a bit dark and hot. The glaze helped add sweetness to the nuts and the loaf itself.

I liked it even more the next day for breakfast, with butter, but when I tried it without butter, it was pretty dry. That was interesting because it is essentially a hybrid of two types of recipes—the pumpkin quick-bread recipe from Joy of Cooking and a butter cake, characterized by the creamed butter and sugar.

Again? What is this?

I really wondered what this might be like if the missing sugar had been indicated, and so I decided to try it again but with another ¼ cup of sugar. It took about 60-70 minutes again to hit 207˚, and using a metal pan this time kept it from getting as lightly scorched out top. I let it sit while for a few hours before adding the glaze, just in case that would make a difference, though nothing I can find in any other cookbook explains why resting for six hours is paramount for a loaf cake.

When I cut into it the next morning, it was very firm, and the crumb was tight. It remained not overly sweet—more like a quick bread than a moist loaf cake. And even the inside pieces were still dry. With butter and some heat, it realizes its calling as a breakfast bread, like the loaves featuring pumpkin and chocolate chips that appear all over during the autumn. But it’s not as sweet as many of those typically are and definitely drier. It’s not the bread or cake for me, which I was able to confirm by making it twice. Maybe I needed to take it out much earlier, between 190-200.

But I’m not going to try it again. Onward to greener pastures…

Considering Omissions and Errors

Since I’m discussing errors, I want to make a note about the use of “till” in two places quoted above. “Till” may sound incorrect or at least too informal to most of us, but it is correct as a synonym for “until,” the word most commonly used in this phrase.

As I’ve previously mentioned, the Oak Valley Cookbook Committee did not intrude editorially, except in what was a clear typographical mistake. This is a common technique in compiled-cookbook-production practices, as the submissions have been solicited, and furthermore, have been solicited from peers. Contacting contributors about a potential mistake may have been fraught. And given the varying types of mistakes that might occur in a recipe, an editorial committee would avoid any social minefields by deciding to not ever be heavy-handed editors—to let the submission and contributor speak for themselves, for good or ill. So unless it’s clear that someone meant tablespoons but wrote teaspoons, most community cookbook compilers let a possible mistake be, for someone else to read, interpret, and make decisions about how to proceed.

How we, as users of the cookbook, might proceed when we encounter an error or omission may depend upon what we know about the contributor, which is what is so fascinating to me about community cookbooks—we can look up who these people are on the internet, or for those of us who are lucky enough to have access to historical material regarding the cookbook’s origin (e.g. McHenry County: Its History and Its People and my parents and other contacts in the community), we can conduct research to learn more about them. It makes me so curious about Verna Howard—who she was, what she was like, why she signed her name this way in The Joy of Sharing, whether she signed other documents like this—checks, cards to her grandchildren, and so on—whether she was a good cook, whether she was known for being absent-minded occasionally, what sort of education she had, her familiarity with language-based conventions, and so on. If I were her contemporary and purchased this cookbook, all of those pieces would help me determine how to understand how to interpret this recipe, whether I trusted the contributor, and whether or not I’d be willing to make one of her submissions.

So who is Verna Howard?

Contributor: Mrs. Harold (Verna) Howard

Born on November 2, 1928, Verna Westman was born in Benedict, ND, to William and Alice (Gullickson) Westman. She grew up on her parents farm and went to school in Benedict, prior to marrying Harold Howard in 1947, in Max, ND, south of the Velva area. The son of Ernest and Caroline (Schmidt) Howard, Harold was born in 1925 near Velva and grew up and attended schools in rural Velva and Ruso. From 1944 to 1946, he served in the US army during WWII and received a Purple Heart for his service. While Harold worked in construction across North Dakota, the couple moved throughout the state before settling in Minot early in the 1950s, where Harold was the co-owner of City Plumbing & Heating. In 1974, they moved to Sawyer, and back to Minot in 2009. Though they were members of Oak Valley during their time in Sawyer, later they joined Our Redeemers Lutheran Brethren Church in Minot. Harold passed in 2011; Verna in 2019.

Verna’s other contributions to The Joy of Sharing are “Buns,” “Whole-Wheat Pancakes,” “Goodie Nut Bars,” and “Baked Beans.” “Goodie Nut Bars” lists her name as “Verna Howard.”

This post is part of an ongoing series in which I make and reflect on recipes and the people who contributed them to the 1985 Oak Valley Lutheran Church compiled cookbook, The Joy of Sharing.