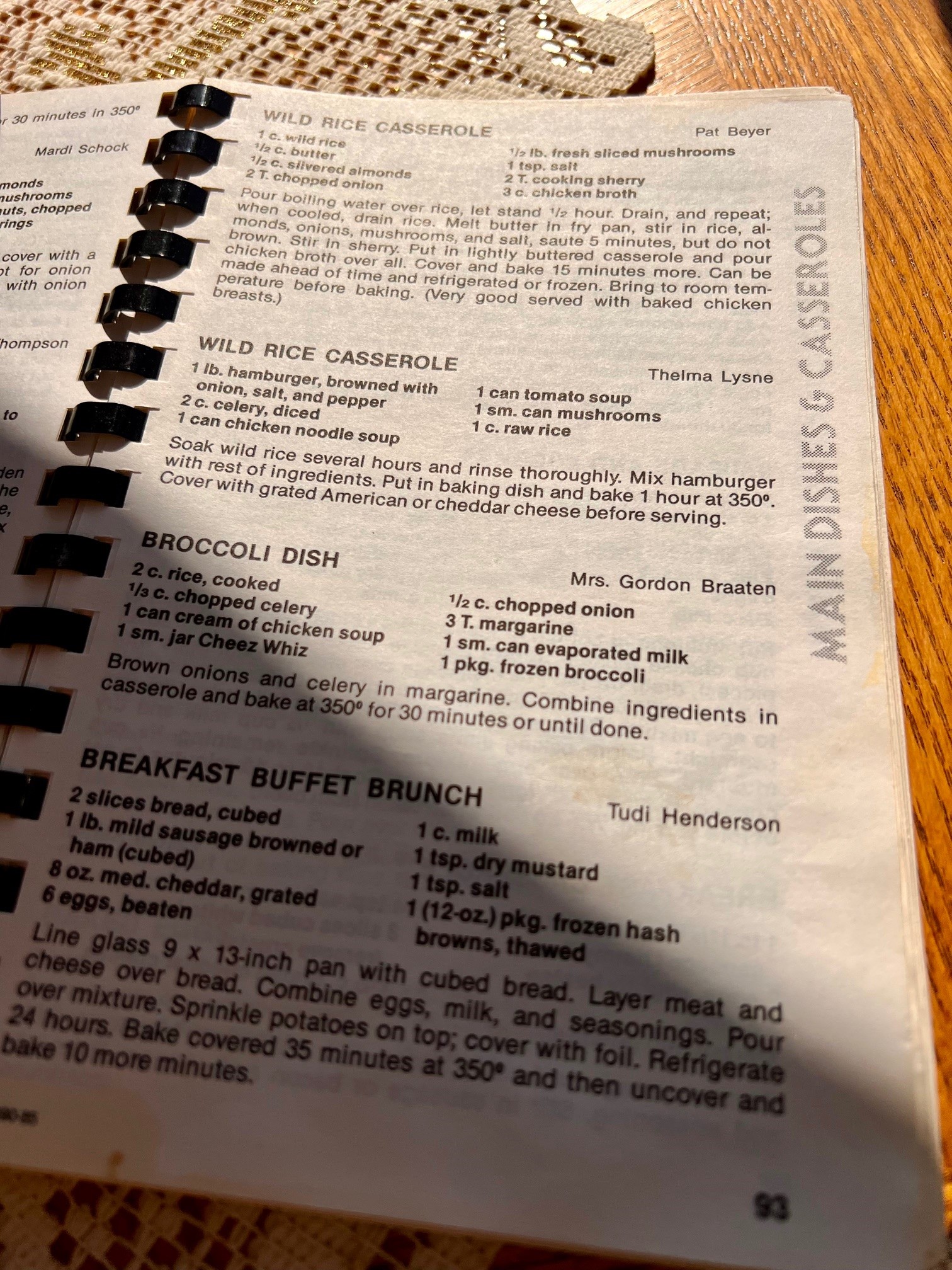

The two best hotdishes I’ve made from The Joy of Sharing were contributed by Thelma Lysne, lifelong resident of Velva, who has been so involved at Oak Valley that she now even leads worship services. Previously, I wrote about Thelma’s life and her recipe “Mrs. Nixon’s Hot Chicken Salad,” which is a salty revelation of gooey cheese and chicken, topped with potato chips: https://blog.cord.edu/karlaknutson/2023/08/10/mrs-nixons-hot-chicken-salad/. And I’ve also loved Thelma’s “Wild Rice Casserole,” housed in the “Main Dishes & Casseroles” section.

Hamburger?

Perhaps I’m sheltered, but I’ve only ever encountered wild rice in a casserole with chicken. I did find another regular rice hot dish using hamburger, and a friend told me about one like that from her church potlucks in her hometown. While I was not familiar with wild rice dishes using hamburger, this hot dish was wonderful—the ground beef and nutty, chewy grains of wild rice complement each other splendidly.

Other than planning ahead to soak the wild rice and taking a little bit of time to brown the hamburger, this recipe was a cinch to put together. I only questioned whether the onion mentioned as part of the browning process with salt and pepper signified diced fresh onion or the dried minced onion likely to be sitting in a spice cabinet (when your small-town grocery store is open limited hours, non-existent, or you’re too far from town to drive in for one ingredient). Living near both my favorite farmer’s market and a grocery store, I settled on diced fresh onion, since the recipe called for fresh celery anyway. Might was well keep cutting, right?

After the hamburger was ready, I transferred it to a large bowl to “mix hamburger with rest of ingredients,” prior to moving it all into the baking dish. How simple! Everything went into that one bowl—the two cups of celery I had diced, the two cans of soup—tomato and chicken noodle, the can of mushrooms, and the drained cup of wild rice.

I mixed everything thoroughly for even distribution and placed it in the oven for the specified one hour at 350 degrees.

You’re supposed to put cheese on the casserole before eating it, but both times I made it, I forgot to add it. If it were pasta or risotto or using Italian flavors, I would have no problem remember that piece. But wild rice and cheese just doesn’t make sense to me, and I think that’s fine.

Delightful Textures

In addition to being easy to throw together in a hurry, the flavor was very nice—earthy and salty, due to the seasoned hamburger and the two cans of soup. It also tasted even better the next day, as the flavors had time to blend (top tip for reheating rice—sprinkle it with some water to rehydrate the rice).

The texture was amazing too—each bite was chewy in the best possible way because of the grains and ground meat—the hamburger and rice provide a chewy textural foundation, contrasted with a smooth piece of mushroom, and then a crunch of celery that hadn’t been softened with sautéing. Each bite offered variety. And the smooth, almost slimy texture of a canned mushroom catapulted me back in time to fighting with my sister over who would get more mushrooms off of our mother’s slice of pizza.

The only issues to note with this dish are that it doesn’t transfer in an elegant shape from baking dish to plate; rather, it creates a classic heap of hotdish. That makes sense since its main ingredient is rice, which, like a liquid, fills its container. And the hotdish seemed to lose heat swiftly once moved onto dinner plates. I suppose we should just eat more quickly.

Manoomin

In her history of American cookbooks, food historian Megan J. Elias explains that recipes with wild rice were featured in Americana cookbooks starting in the 1950s: “because wild rice was a highly valued, ‘gourmet’ product but also indigenous to North America, it was a favorite of writers who wanted to claim a noble American food past” (134). Elias further notes that these cookbooks mentioned but did not describe the history, origin, or harvesting methods of the indigenous peoples for whom wild rice was a traditional foodway, reductively tokenizing wild rice as the only contribution of Native Americans to American cuisine, attributing the rest of contemporary foodways to the influence of European immigrants (134).

Lois Ellen Frank’s excellent cookbook Seed to Plate, Soil to Sky: Modern Plant-Based Recipes Using Native American Ingredients (2023) does more than remind readers of wild rice’s original provenance. Frank definitively reclaims manoomin, “the food that grows on the water,” as a foodway central to Native American cultures in North America: “Manoomin, or wild rice, is a Native American grain that is part of Native communities in northern Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Canada” (52). This reclamation places the Anishinaabe of the White Earth Nation and their traditional harvesting practices at the center of discussions regarding how to source wild rice.

Many contemporary Midwestern cookbooks approach wild rice recipes similarly, acknowledging and supporting the Midwestern Native communities who harvest and sell wild rice today in the introductions to recipes using this fantastic ingredient. Chefs like Paul Fehribach, Lenny Russo, and Amy Thielen introduce their wild rice recipes by articulating the importance of traditional harvesting practices and supporting Native harvesters by purchasing their products, as well as the perils of commercial wild rice production efforts. Fehribach directly ties this quintessential Minnesota ingredient to another important Minnesota foodway—the hotdish, introducing his “Duck and Manoomin Hotdish.” I’m eager to try it—duck season opens next week and pheasants soon after that; I imagine either would be delicious, though some finagling would be necessary with the leaner pheasant.

The three wild rice hotdishes in The Joy of Sharing point to this ingredient’s popularity in North Dakota in the latter decades of the twentieth century. While I don’t remember the first time I tasted this delicious grain, I do remember eating wild rice growing up in North Dakota. Not at home, though—my father didn’t like any rice (How is that possible?), and so wild rice and my beloved chicken and rice casseroles weren’t something my mother was going to bother to serve if one fourth of the diners wouldn’t be interested in eating it. If we did have some rice, it was Minute Rice, to go with a can of chow mein. My mom doesn’t remember having any rice in her household when she was growing up either. Potatoes really ruled the side-dish world.

Instead, rice was a treat when dining out. My mom and sister and I would go out for Chinese food with fried rice, which is how I fell in love with all rice. It was so delicate, yet so filling and flavorful—oil and butter will do that. I ordered it as a side dish on the rare occasions our larger family went to a fancy restaurant called “Field and Stream” (a windowless building with a “real” stream flowing through it). I also recall ordering chicken and wild rice soup and loading up heaping spoonfuls of chicken and rice hotdishes at potlucks—but not necessarily wild rice. I imagine the expense of this grain is why; unless you were aiming for a conspicuous display of wealth or an act of generosity, you might save an expensive ingredient for a special meal at home, maybe serving it for company.

As a child or teenager, I don’t think I had an understanding that wild rice was harvested only one state over—the prairie of central North Dakota seemed worlds away from the forests speckled with lakes in the Walker, Minnesota area, home to the White Earth Nation. I learned about and embraced these geographical and cultural differences as an adult exploring Minnesota’s state and national forests on foot and bicycle. What’s amazing about Minnesota’s and North Dakota’s geographical diversity is how the different landscapes of each state and even within each state create different possibilities—for what is grown, caught, or hunted. What’s also amazing is how all of the different foods of Minnesota—lake trout, venison, sugar beets, corn, and yes, wild rice—are embraced as quintessentially Minnesota. In 1977, manoomin was adopted as Minnesota’s official state grain. While these two neighboring states share much, they are fascinatingly, excitingly distinct.

I wonder what relationship the contributors of these recipes had to wild rice. Did they travel and love to pick it up in grocery stores and gift shops? Was it a favorite in restaurants? Did they spend a lot of time in Minnesota or have relatives or friends there? Were they aware of the history of wild rice as an indigenous ingredient harvested by Native American tribes across the Great Lakes region? Were they voracious cookbook readers, up for exploring new recipes and experimenting with new ingredients? Was wild rice soup as ubiquitous in central North Dakota in the 1980s as it is in the Red River Valley now, a mere two hours from where much wild rice grows? In Fargo, it’s not hard to find wild rice when you head out to eat, and I often pair the ooey gooeyness goodness of chicken and wild rice soup, which, if thick enough, does seem sometimes like a risotto or a hotdish (decadent and wholesome all at the same time) with something less clearly related, just because I can’t resist trying it.

This post is part of an ongoing series in which I make and reflect on recipes and the people who contributed them to the 1985 Oak Valley Lutheran Church compiled cookbook, The Joy of Sharing.