Cooking and baking my way through The Joy of Sharing raises many memories of food from youth in central North Dakota. While recently reminiscing about my maternal grandmother’s sweet, gooey date cookies and her date bars with a crumble topping, I began looking through the cookbook to see what recipes involved dates. I picked up a large bag of whole pitted dates at Costco and got down to the seriously involved work of chopping them up. I planned to make Verna Shock’s “Date-Nut Muffins,” from the “Breads & Rolls” section of The Joy of Sharing, but since I was already chopping, and since it’s a sticky business, I kept going until I had enough chopped dates for Mabel Olson’s “Date and Nut Torte,” in the “Pies, Pastry & Desserts” chapter, as well.

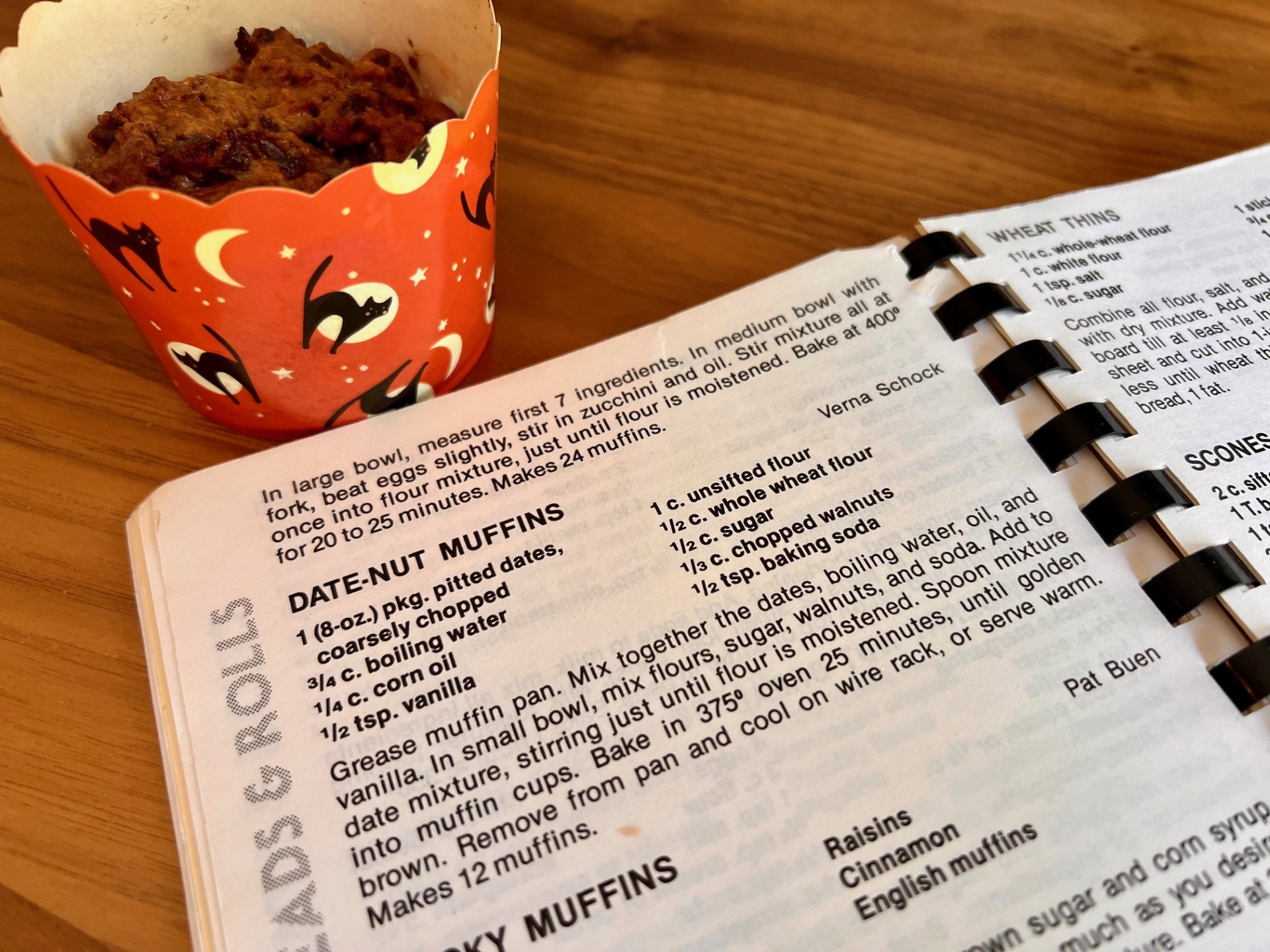

Date-Nut Muffins

Making only twelve standard-muffin-tin-sized muffins, this is a small recipe. But given how filling these muffins are, 12 is plenty to have around for a few days. I ended up freezing two-thirds of them since I couldn’t get through too many of them before they were in danger of becoming stale. The satisfying nature of these muffins stems from the chewy and hearty ingredients: high-fiber dates, protein-rich whole wheat flour, and crunchy, healthy-fat-filled walnuts.

After loading my muffin pan with festive black-cat themed muffin cups (it’s fall, ya’ll!), I debated whether the instructions to “grease muffin pan” meant to add some sort of liners or to grease the cups. I decided not to grease the cups, but I wish I had, as the muffins were a bit difficult to remove from the cups cleanly.

The next step was to mix the wet ingredients, including boiling water. Handily, the need to have this ingredient prepared had been indicated in the ingredient list, and so I had already boiled enough water for both the ¾ cup I needed and for a cup of tea to enjoy while I waited for my muffins. I added the boiling water to the dates, vegetable oil, and vanilla, and then mixed together my dry ingredients—sugar was specified as dry instead of wet, which was surprising, as well as the walnuts, baking soda, and the two types of flours. The specifications for the flours were fascinating—the “1 c. unsifted flour” stood in contrast to the ½ c. whole wheat flour. The “unsifted” qualification made me presume I needed to sift the whole wheat flour.

Following the instructions further, I added the dry mixture to the wet one, “stirring just until flour is moistened,” then placed this thick, tacky batter into the cups and placed them in the oven at 375˚.

Planning to check on the internal temperature to avoid overbaking, I set my timer for 15 minutes and did not expect these muffins to take the entire recommended 25 minutes.

But they did! I eventually pulled them out after about 23 minutes, when they registered just over 200˚on my probe thermometer. They smelled amazing and looked a deep brown, due to the dark caramel-shaded dates and whole wheat flour.

Hmm…Once More

Since the flavor profile leaned savory, I ate a buttered date muffin with my salad for lunch. I was surprised at how dense and slightly dry they were. I was disappointed, as I hoped for a moist muffin, as one always does. I tried again in the afternoon, warming up my muffin this time and again, adding some nice European butter, and this time, they were delicious—moist and gooey inside. The heat made a difference, as it often does, but it shouldn’t be necessary.

Certainly, user error played a role: between combining the dry ingredients and taking pictures, I was concerned I took too long to add the dry ingredients. I’m sure the boiling water had cooled down too much.

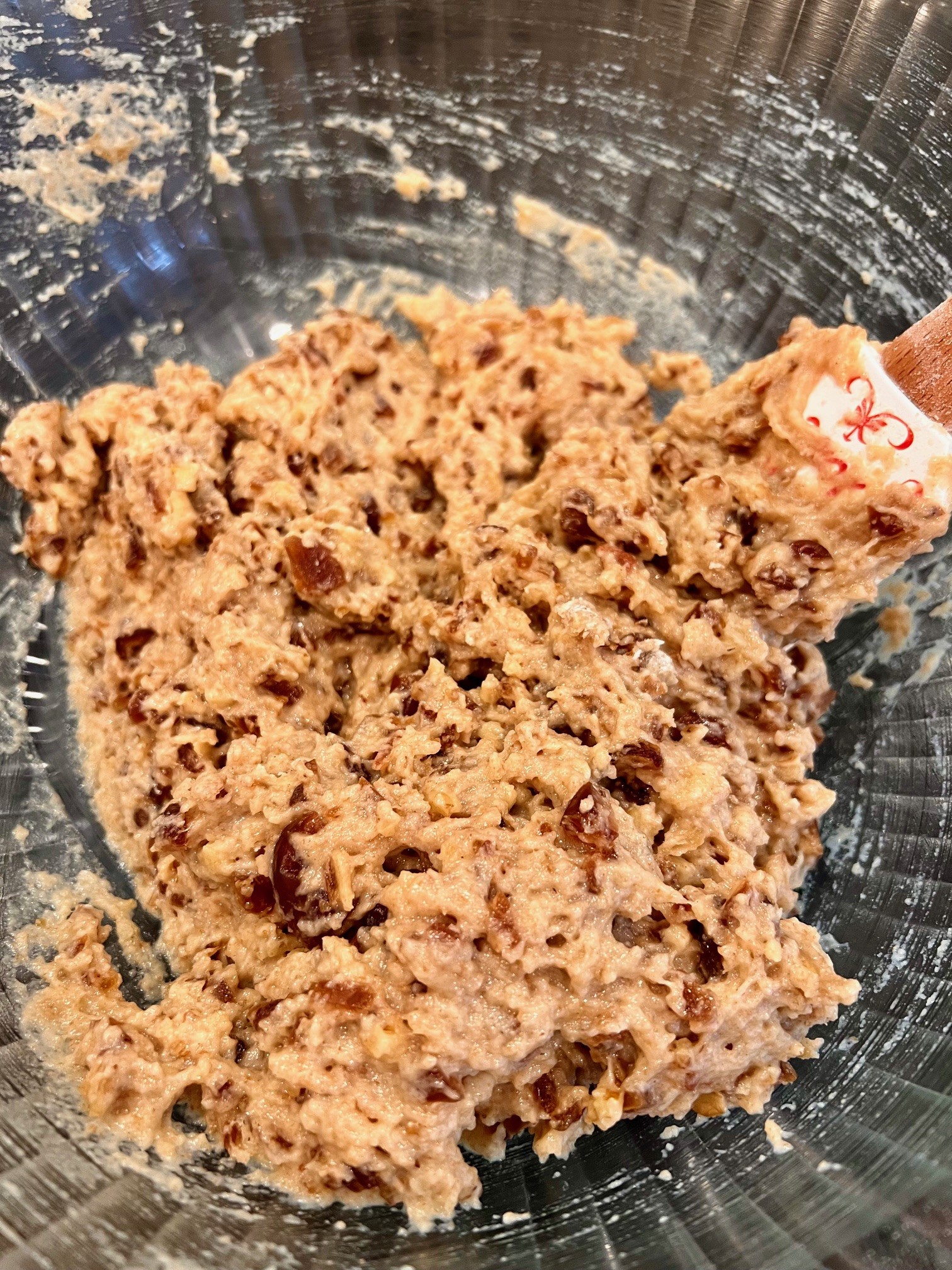

So I made them again, this time adding the dry ingredients immediately after pouring the hot water into the date mixture. And the batter was different.

Much less sticky, it adhered to itself and dropped gracefully off the spoon with a slight prod from my spatula, landing cleanly in the bottom of the muffin cup.

After 15 minutes in the oven, the muffins were at 180˚and after 20 minutes, all but two muffins were registering the requisite threshold, just over 200˚ and luckily, none over 204˚. I put the pokey ones back in for two more minutes to reach the right temperature. The tops were beautiful—a jagged landscape of varying shades of brown, with visible morsels of date and walnut. I had high hopes for clean-looking cups since the batter had not splattered in the process of filling the cups, but alas, greasing the cups with cooking spray affected their appearance. The benefit was that the cups rolled smoothly off the intact muffin.

This time, they were amazing! Still dense, but with a tender interior and more open crumb. The pieces of date add sweetness and chewiness, and the shards of walnut offer a firm contrast to the dates’ texture.

My top tip for these muffins is to prepare both wet and dry mixtures, prior to adding the boiling water and the final blending step. And consider using a food processor to make quicker work of chopping the dates.

Contributor: Verna Schock

I’ve made other recipes (Shrimp Cocktail and the forthcoming “Scalloped Cabbage”) by Verna Schock, one of the six members of the Cookbook Committee, the subgroup of the Oak Valley Women’s Group who compiled and edited The Joy of Sharing. She is still an excellent and enthusiastic cook and baker, and read more about her life in my previous post about a shrimp dip: https://blog.cord.edu/karlaknutson/2023/07/31/food-for-fun-in-the-sun-part-ii/.

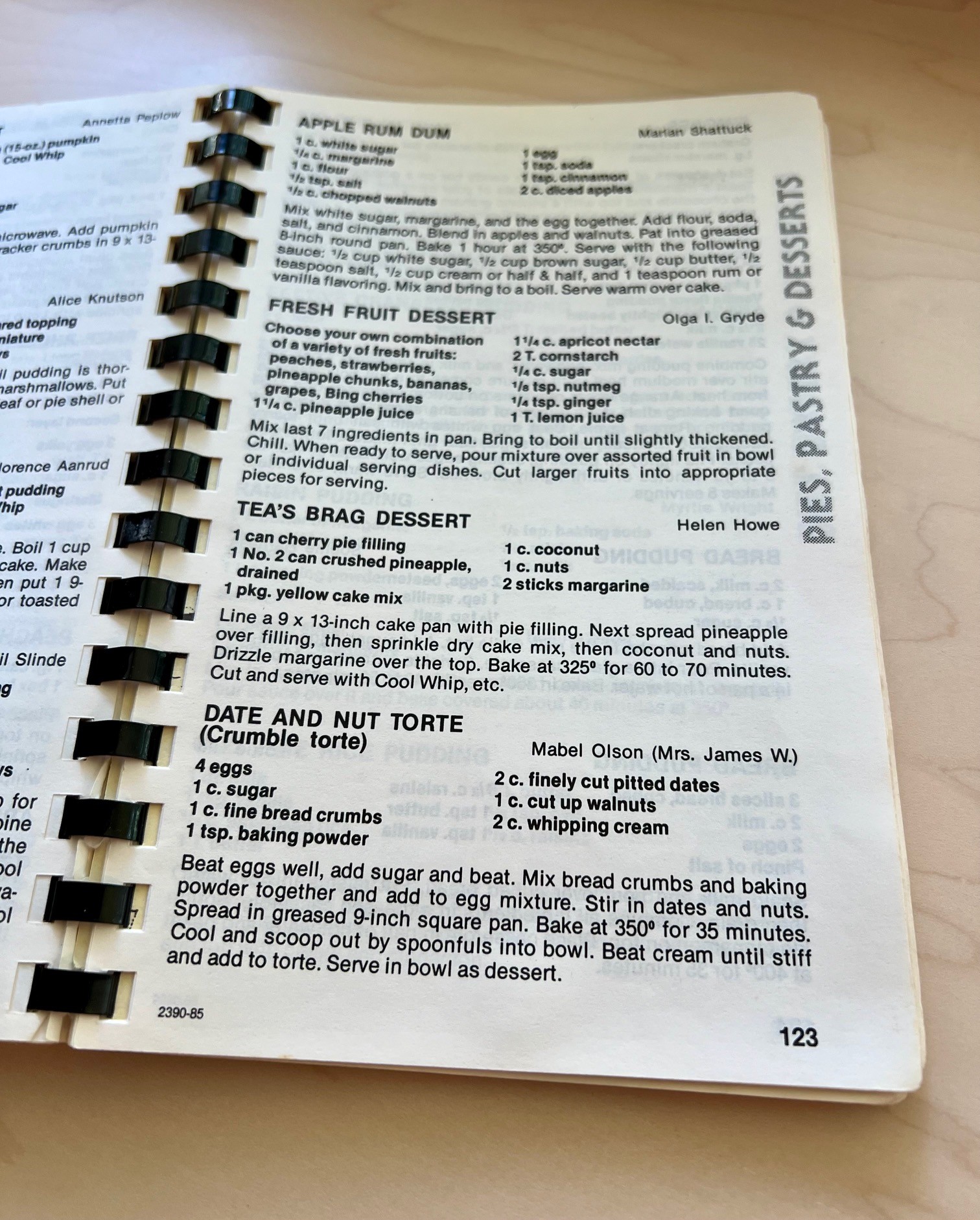

Date and Nut Torte (Crumble Torte)

Though it sounds posh, “torte” is German for “cake.” It signifies a distinctive type of cake, one many Americans who grew up with the boxed cake-mix craze might be surprised is actually a cake.

And this is a posh dessert. And it is delicious. And deliciously simple. But artfully disguised by sophistication.

Follow the Imperatives

The recipe itself is a set of imperatives, all clearly laid out in discrete, easy-to-follow steps, despite the comma splice in the first “sentence,” a common sentence boundary error in which two independent clauses are incorrectly spliced together using only a comma. After whisking the required four eggs, I added the cup of sugar and mixed further.

In another small bowl, I stirred together the ingredient that surprised me the most—the cup of fine breadcrumbs, used more often in savory recipes, in my experience—with the teaspoon of baking powder.

Then, I added that to the egg and sugar mixture, before folding in the dates and walnuts.

While the recipe recommends baking the torte in a 9-inch square pan, I decided that this dish was an occasion for using my fancy new fluted-edge tart pan, given that the dessert would be eaten with whipped cream.

While it baked, I began work on the whipped cream prescribed by the recipe. After retrieving the mixing bowl and whisk attachment from chilling in the freezer, I followed the directions faithfully: “Beat cream until stiff.” But I wasn’t sure what would happen, as whipped cream recipes call for added sweetness, typically provided by powdered sugar and vanilla. In contrast, this recipe appeared to imply that only whipping cream itself would be necessary, in two places: the specification of “2 c. whipping cream,” the last item in the ingredient list, as well as the previously quoted instruction regarding its preparation. Was I missing something?

I wasn’t. This chilled, stiff cream was not sweet in any way; it literally was light, airy whipped cream. Intending to serve the torte the next day, I put the cream in the fridge, washed the bowl and whisk, and tucked them back in the freezer. The next morning, I tasted the whipped cream again to confirm its need of adornment, and then put it back in the chilled mixing bowl, added the sweet ingredients, and whipped it to combine. Voila! Whipped cream.

After 35 minutes in the oven at 350˚, it was a beautiful, light-golden brown with attractive variations in texture visible through the top.

While further instructions indicate that the torte should be cooled, at which point you should “scoop out by spoonfuls into bowl. . . .Serve in bowl as dessert.” These instructions imply similarities to puddings, like bread pudding, but I’m a bit surprised by that, given how easily my torte was sliced into wedges and plated. It was mobile too, as I transported two slices with baking cups of whipped cream to some friends on campus for an afternoon treat.

Tortes, Defined

Though torte means cake, “Date and Nut Torte” doesn’t look like most of the cakes I have ingested, viewed, or made during my lifetime. Rather than being light and fluffy, with an open crumb, it’s dense and remains approximately the same height as the batter once poured into the pan. Ellen Morrissey accounts for these differences in “What Is a Torte—and How Is It Different From a Cake?” noting that tortes use “nut flour or breadcrumbs rather than flour, a standard ingredient in traditional cakes. As a result, tortes are typically heavier than cakes, almost like a light-textured fudge.” Lack of flour also leads to their shape: “they don’t rise in the oven. This makes them shorter and flatter than traditional cakes” (https://www.marthastewart.com/2124450/torte-linzer-torte-sacher-torte-explained).

Both Mabel Olson and I have anticipated pleasing serving methods. James Beard’s American Cookery includes a recipe for “Date Nut Torte” which also “is often served rather more like a pudding, topped with whipped cream. Or, it is made in a thin layer, cut into thin strips and served as a tea cake” (667). Similar in most respects, this recipe deviates from Olson’s by using flour rather than breadcrumbs, as well as an egg, and butter. Further into his chapter on cakes, however, appears “Nut Torte or Nuss Torte,” an almost identical recipe to that in The Joy of Sharing. Describing it as a “typically Viennese dessert” and “of firmer consistency than our traditional cakes,” Beard’s version creates an airy concoction of egg yolk and sugar, then breadcrumbs and nuts, then a foam of frothed egg whites, cream of tartar, and salt. The presentation is fancy too: “This cake is usually cut in half and filled with coffee, chocolate or mocha cream, and is also often iced with the same mixture and sprinkled with chopped toasted nuts, either on top or just on the sides” (688). That certainly sounds incredible.

Dates

While all the adults who tried these date-filled treats enjoyed them, my daughter did not like the chewy texture of the dates. That was explained, however, when I happened to page through the chapter on Lutheran bars in Lutheran Church Basement Women and saw the annotation to the recipes for “Date Squares”: “Little kids won’t eat these” (75). Ah, like a window into my kitchen!

I’ve loved dates since a teen—they are yummy, chewy, and sweet; Harold McGee points to their hint of caramel aroma (383). But like raisins, their texture is unique, and that may account for the children’s displeasure at being offered a date-based treat. Dates are the fruits of Phoenix dactylifera, a desert palm tree whose “cultivation is of prehistoric origin” in the “hot, dry region stretching from N. Africa through the Middle East to India,” according to Philip Iddison’s article on dates in The Oxford Companion to Food. Though there are many types of dates, the main varieties are grown for commercial production across the world in hot and dry area, including California and Arizona in the United States (Iddison).

Dates remain very important in the Middle East, where soft dates are typically eaten fresh, rather than the semi-dry dates common in Western nations. During Ramadan, many Muslims all over the world break their fast with dates, following a tradition of the Prophet Muhammad (see, for example, Roger Owen, Oxford Companion to Food, among others). And the United States, dates have been recently touted for their healthy qualities.

For me, though, they remain nostalgic, until now a remnant of my grandmothers’ kitchens.

But no longer.

Contributor: Mabel Olson (Mrs. James W.)

Mabel Ayers was born on June 21, 1932, to Richard and Irene Park Ayres, in Kongsberg, North Dakota, south east of both Voltaire and Velva. When I was a child, Kongsberg, was a ghost town, with a post office, bank, and a few other buildings still standing, but when Mabel was a child, her father was the town’s Soo Line Depot agent. Mabel graduated from Velva High School in 1949, and as a registered nurse from Trinity Hospital School of Nursing in 1952, prior to marrying James Ward Olson in June of 1953. A year older, James (Jim), the son of Carl and Myrtle Wilmovsky Olson, was born in the Voltaire Hotel on March 15, 1931; his mother operated the hotel’s restaurant from 1929 to 1935. The couple lived and worked in Rugby (Mabel as an RN, and Jim as an owner of a surplus store) until 1954, when they moved to Velva. In Velva, Jim farmed, owned the Star City Reality, the HiWay 52 Coal Company, and the Hotel Berry. Together with their five children, Jim and Mabel lived in the Hotel Berry, operating it as a hotel until 1979, and after that opening it for historic tours, after it was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1982. I remember visiting it during elementary school field trips. Jim passed in 2000; Mabel resides in Velva.

Last summer, I had the chance to visit with Mabel’s daughter-in-law, Carolyn Olson, and her son Jim Olson. Carolyn was a member of the Oak Valley Women’s Group’s Cookbook Committee, and we had a wonderful conversation about that experience, as well as the role of cooking and food in her life. She mentioned what a good cook Mabel was, as well as her mother, Marilyn Anderson, another contributor to The Joy of Sharing, who served for years as the very talented Oak Valley pianist and organist. Mabel’s other contributions to the cookbook include “Wassail Bowl,” a festive holiday punch I’m eager to try this winter, “Blueberry Pancakes” (forthcoming soon!), “Bean Pickles,” “Chow-Chow,” a pickled vegetable mix, “Swedish Meatballs,” and “Shrimp Salad.” There’s a lot more I’m looking forward to making here!

This post is part of an ongoing series in which I make and reflect on recipes and the people who contributed them to the 1985 Oak Valley Lutheran Church compiled cookbook, The Joy of Sharing.