Cabbage actually is…all around.

Or is that love?

Both really. But is there a movie about cabbage’s omnipresence yet?

In addition to beloved cabbage-based delicacies like sauerkraut (yum….and it’s October! Grab an Octoberfest-inspired beer and a sausage to go with your kraut), coleslaw, stir-fries, and egg rolls, many varieties of cabbage can be found in fine dining establishments across the United States. The title of Kim Severson’s article in the New York Times in March 2024 reveals its status: “The Coolest Menu Item at the Moment Is . . . Cabbage?”

Severson explains its burgeoning appeal: “Cabbage has the advantage of being especially cheap and bountiful, with a long shelf life—a single head seems to last forever in the refrigerator. It gained ground as American menus added creative dishes influenced by China, India and other Asian countries, where cabbage is an essential ingredient. Kimchi has helped mightily. Its meteoric rise has been buoyed—much to the chagrin of some—by the interest in all things fermented and gut-friendly.”

Yet, its ubiquity as “a global culinary workhorse for centuries,” which “has fed generations of American immigrants” means that this sheen of glamour is new, a renaissance and reimagining of a sulfurous family of vegetables, a “group of formidable chemical warriors with strong flavors” (McGee 321).

For perhaps these reasons, cabbage may not have been received with great acclaim on the home dinner table. But at my house growing up, cabbage was part of what we called my dad’s “Happy Meal”—the meal that made him most happy: a hamburger steak, boiled potatoes topped not with gravy but with boiled green cabbage in a sauce of half and half and pepper. Rounding out the meal was the ubiquitous glass of milk (called in my house “milk glasses” not “water glasses”) and white bread with butter. In the summer, a Happy Meal also involved fresh veggies constituting a “relish tray,” which accompanied all noon and evening meals—sliced cucumbers, tomatoes, whole radishes, and green onions—and was adapted for transport if the meal would be taken in the field. Interestingly, this is the only cabbage dish my mother makes for my father at home, though he might throw some in the crockpot if he’s cooking. Typically, he gets his cabbage on the outside, now often at the Sons of Norway, as we sample various soups at lunchtime. I like cabbage too.

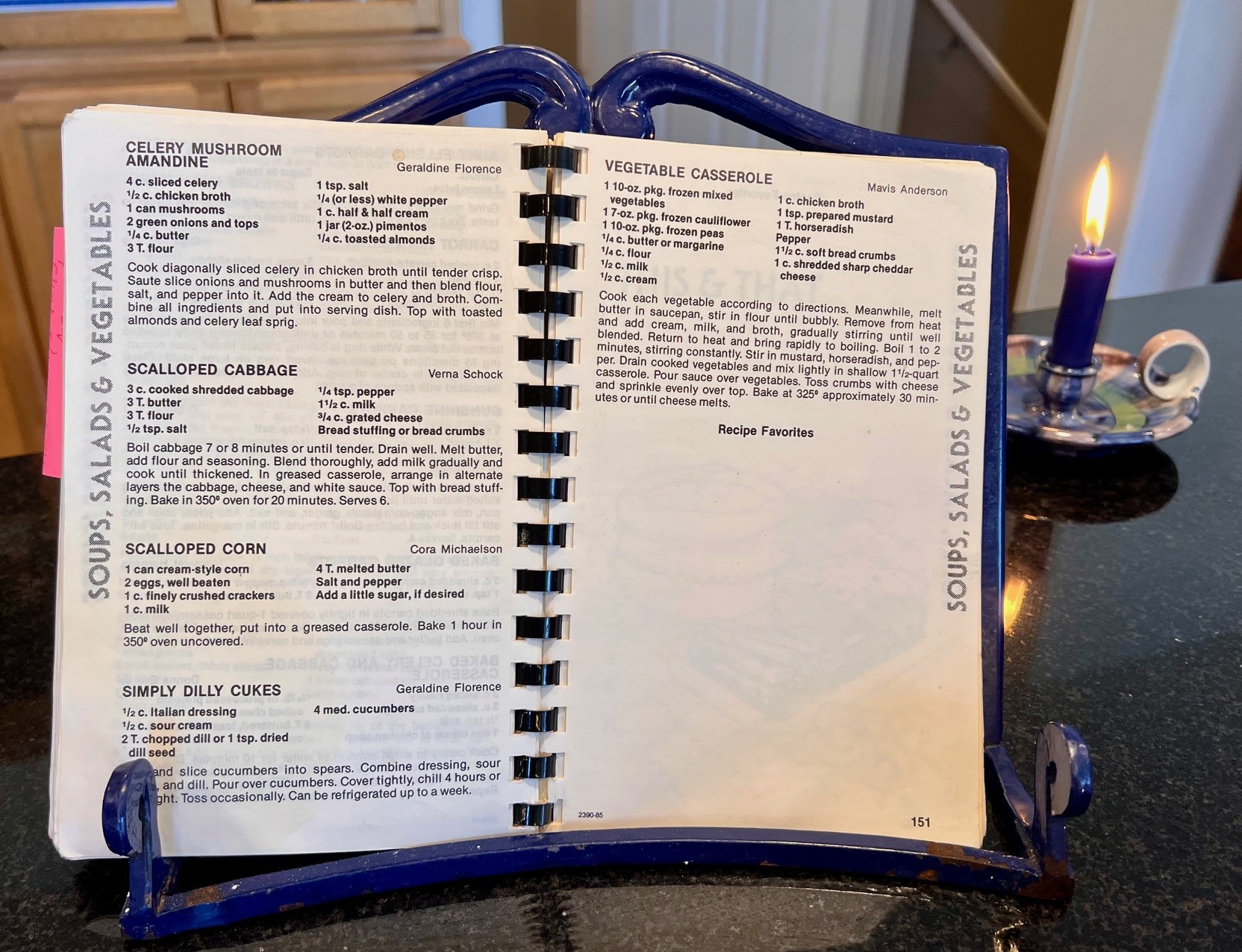

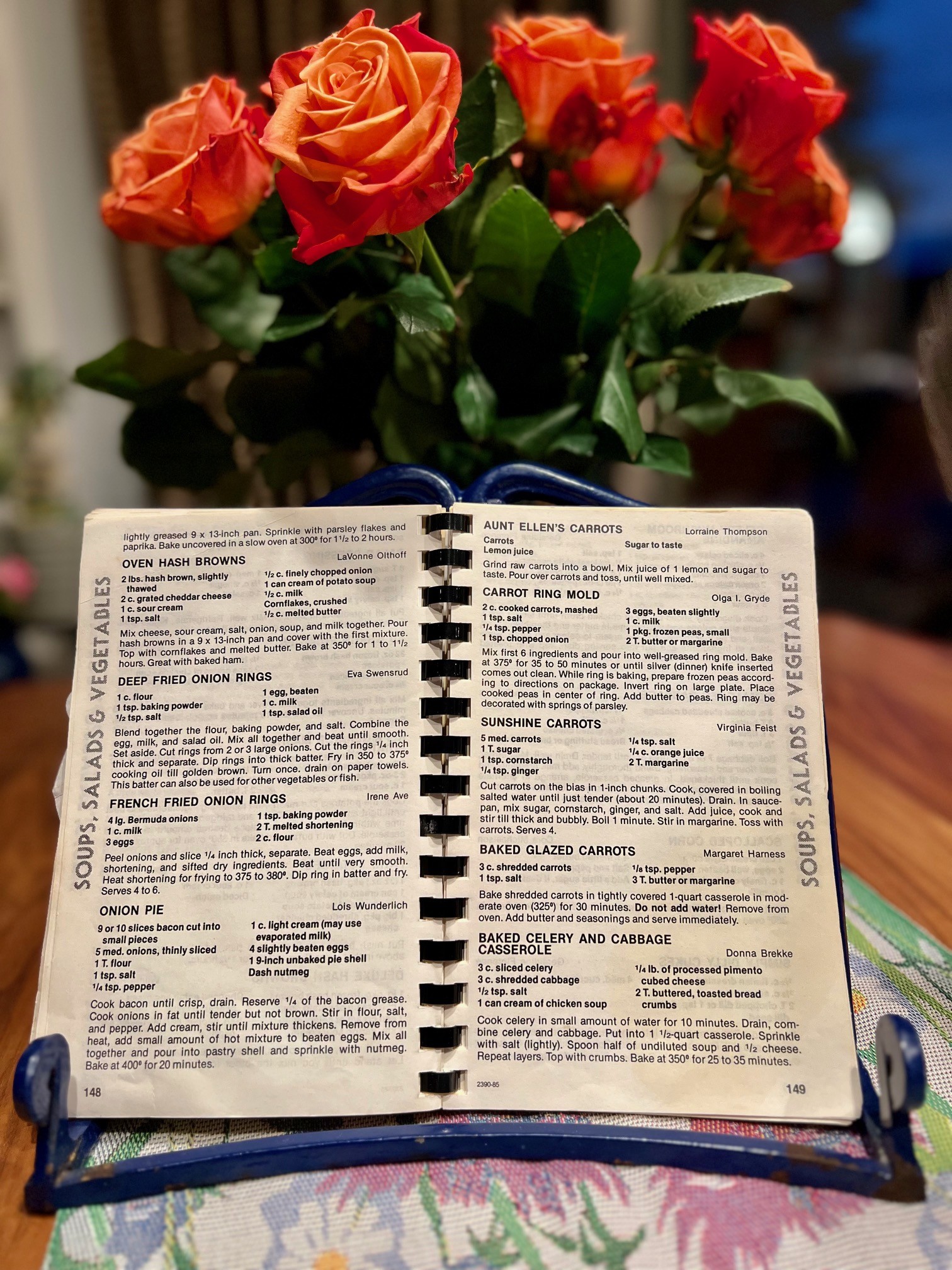

The Joy of Sharing includes two cabbage casserole recipes in the “Soups, Salads & Vegetables” section: “Scalloped Cabbage” contributed by Verna Schock and “Baked Celery and Cabbage Casserole” submitted by Donna Brekke.

Scalloped Cabbage

Despite starting with boiled cabbage, a preparation that does not typically draw out the most flavor from an ingredient, this turned out to be a pretty tasty side dish. I’m not going to make it again, but I was happy enough to cut out a small square to eat as a side with other leftovers for a few lunches.

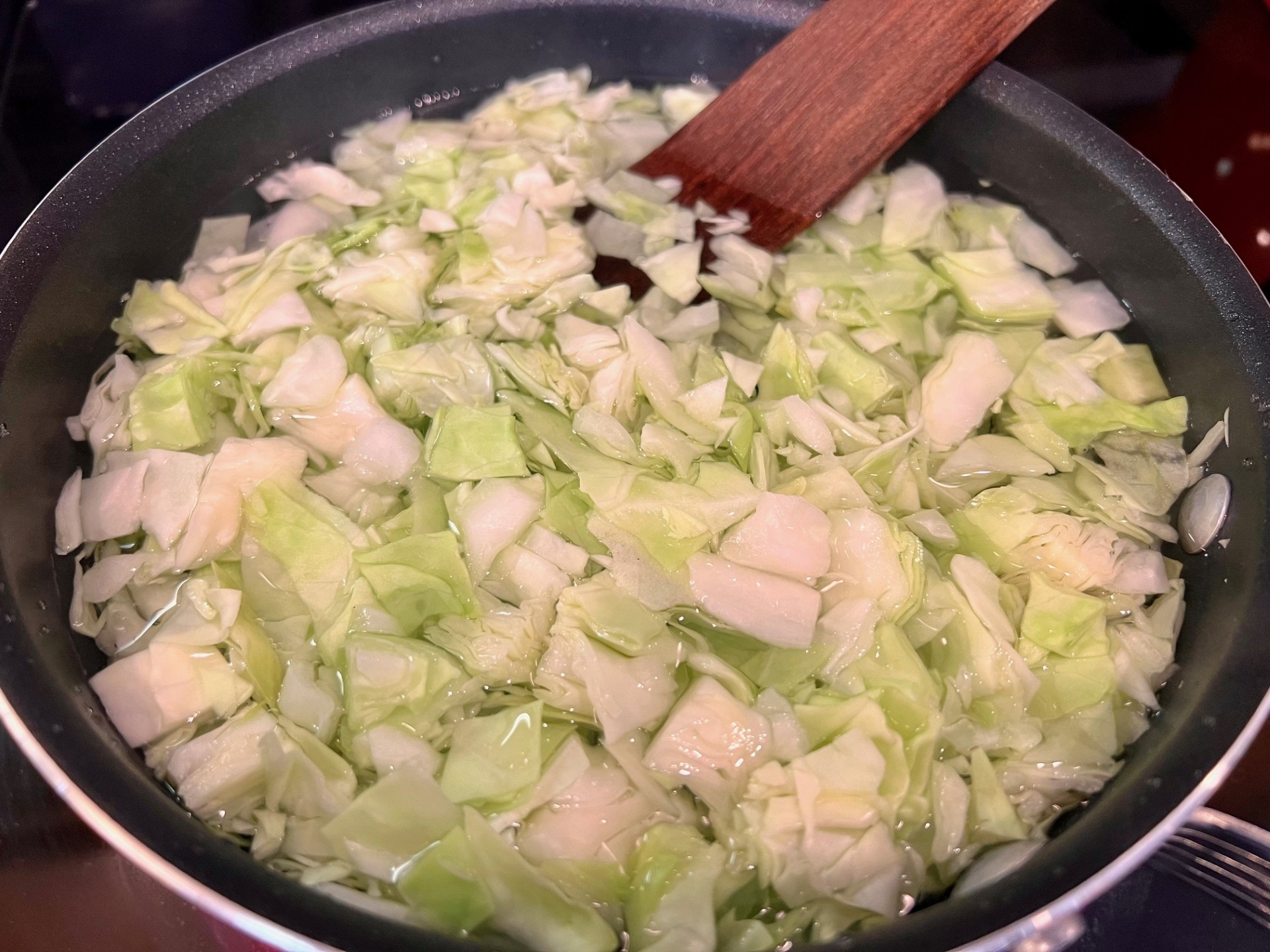

After dicing half a head of cabbage from my local farmer’s market to reach the required three cups, I carefully placed the cabbage in the boiling water for about seven minutes, prior to draining it.

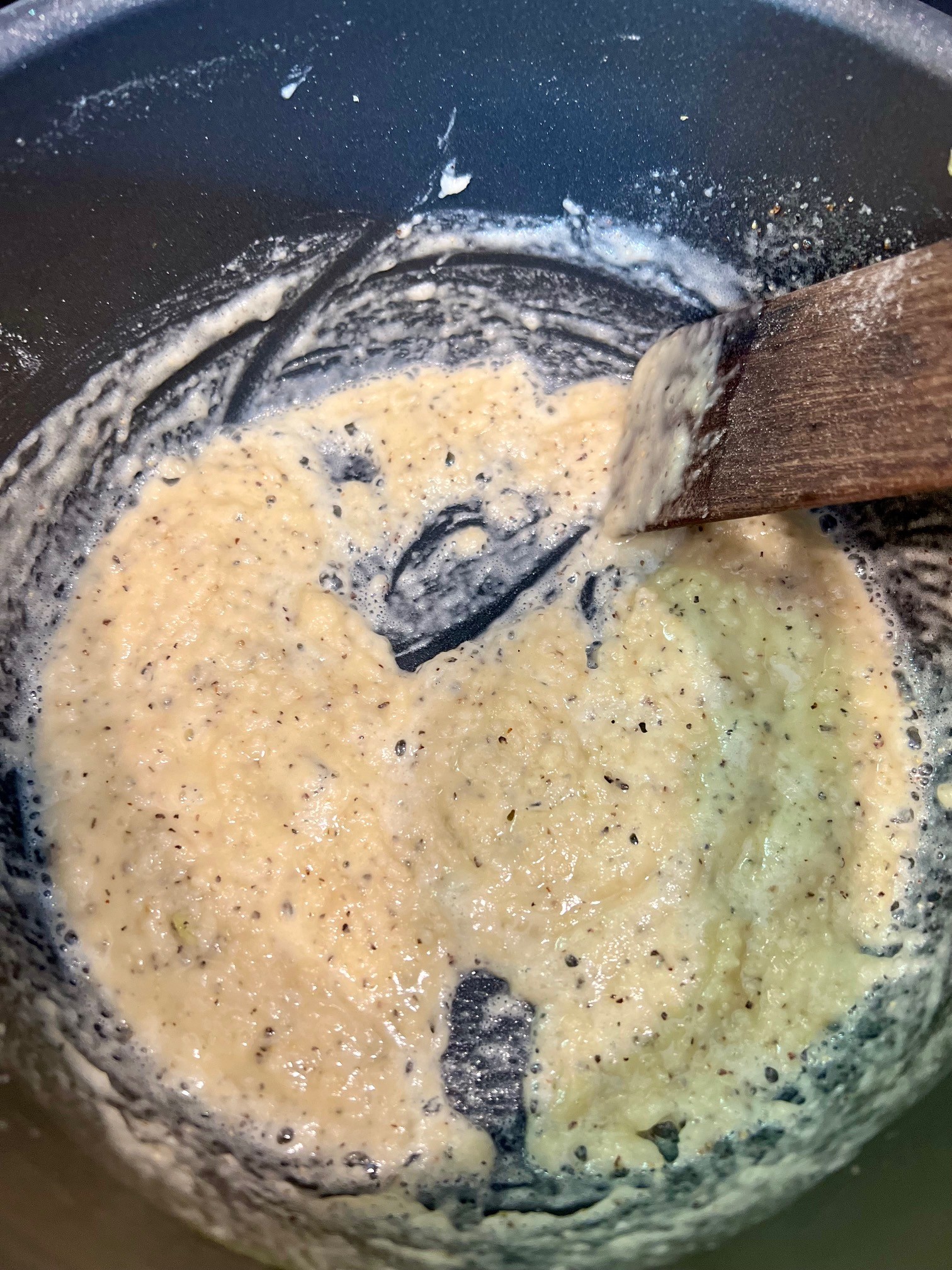

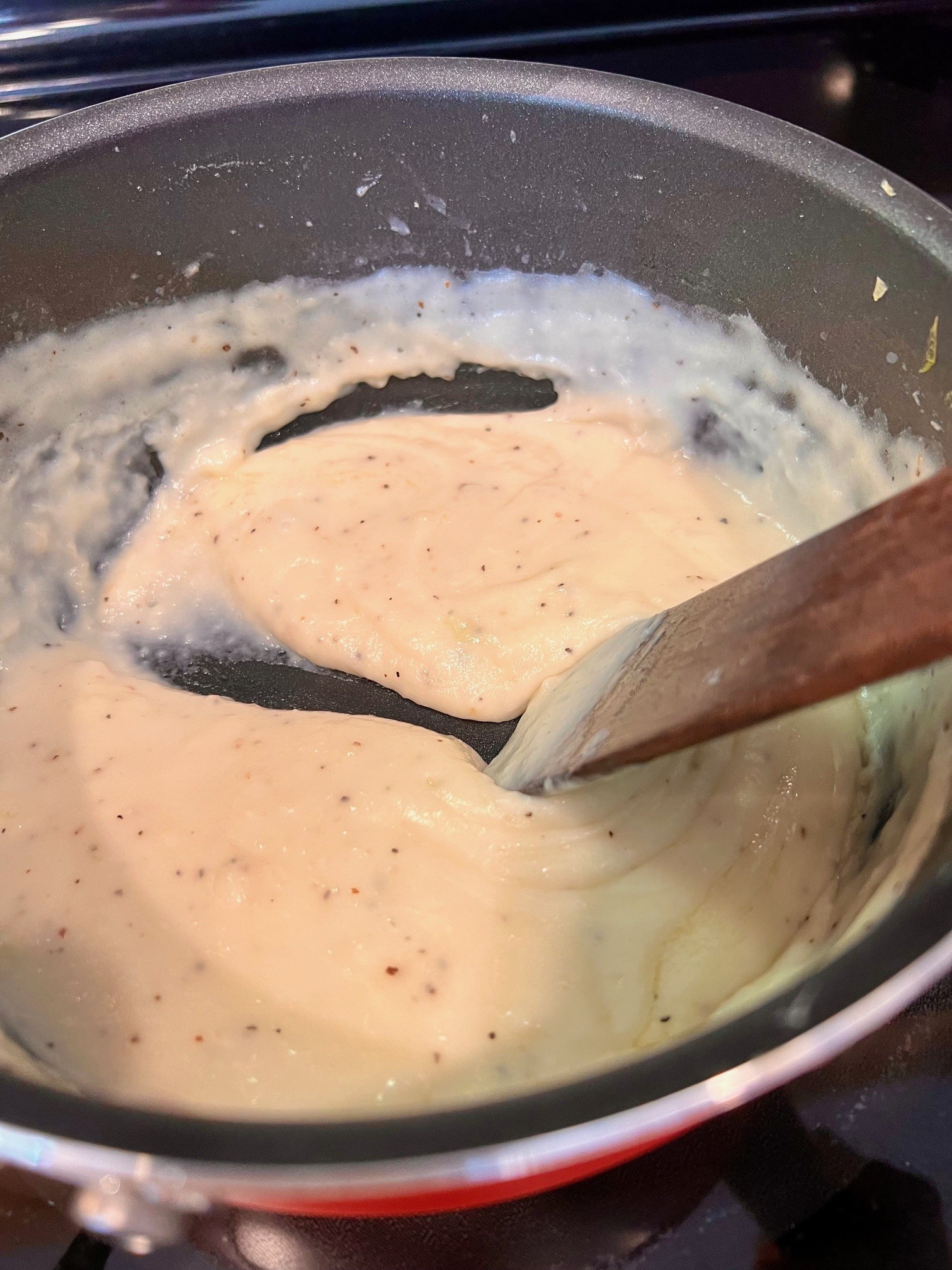

Though the phrasing may belie it, the next step is also on the stove: “Melt butter, add flour and seasoning. Blend thoroughly, add milk gradually and cook until thickened.” Until the final command, nothing gives the reader the sense that this is a process to be done on the cooktop. Of course, if you’ve read the ingredient list, it’s clear that you have the ingredients for a roux and a béchamel sauce, and when you read procedure, it’s very clearly that of making a béchamel.

But it may throw a reader not to see any indication of using a saucepan or what level of heat to use. Our contributor, Verna Schock (for Verna’s bio, please see: https://blog.cord.edu/karlaknutson/2023/07/31/food-for-fun-in-the-sun-part-ii/), may have expected any cook planning to make this recipe to know the casserole formula and to expect a béchamel.

This is a layered casserole too—the cabbage first, then the shredded cheese, then the béchamel; I had enough ingredients to do this twice.

I then took a page from Ina Garten’s advice (most recently from making her overnight mac and cheese recipe for our English department annual potluck) and mixed breadcrumbs with melted butter prior to sprinkling it on the top of the casserole. The recipe’s instructions specify “bread stuffing or bread crumbs” but offer no amounts so I poured some into the bowl onto of the melted butter, ensuring they didn’t get too dry.

After 20 minutes at 350˚and a couple minutes under the broiler to add some nice golden color to the top, the casserole was ready.

“Scalloped Cabbage” would be interesting with a stuffing mix—thicker pieces of bread, adding seasoning—that could really amp this recipe up. And it needs it. It was fine, but it’s mainly satisfying in a salty, buttery-breadcrumb way, which isn’t ideal—the breadcrumbs shouldn’t be the element you remember. This may be because it was a fairly thin casserole, even in a small casserole dish.

Baked Celery and Cabbage Casserole

This dish caused consternation in my household—first, for me as the cook wondering about several features of the recipe and for my daughter and husband, who found the lingering boiled celery scent nauseating. And wow, did it linger…I needed to open the windows and light candles the next morning too.

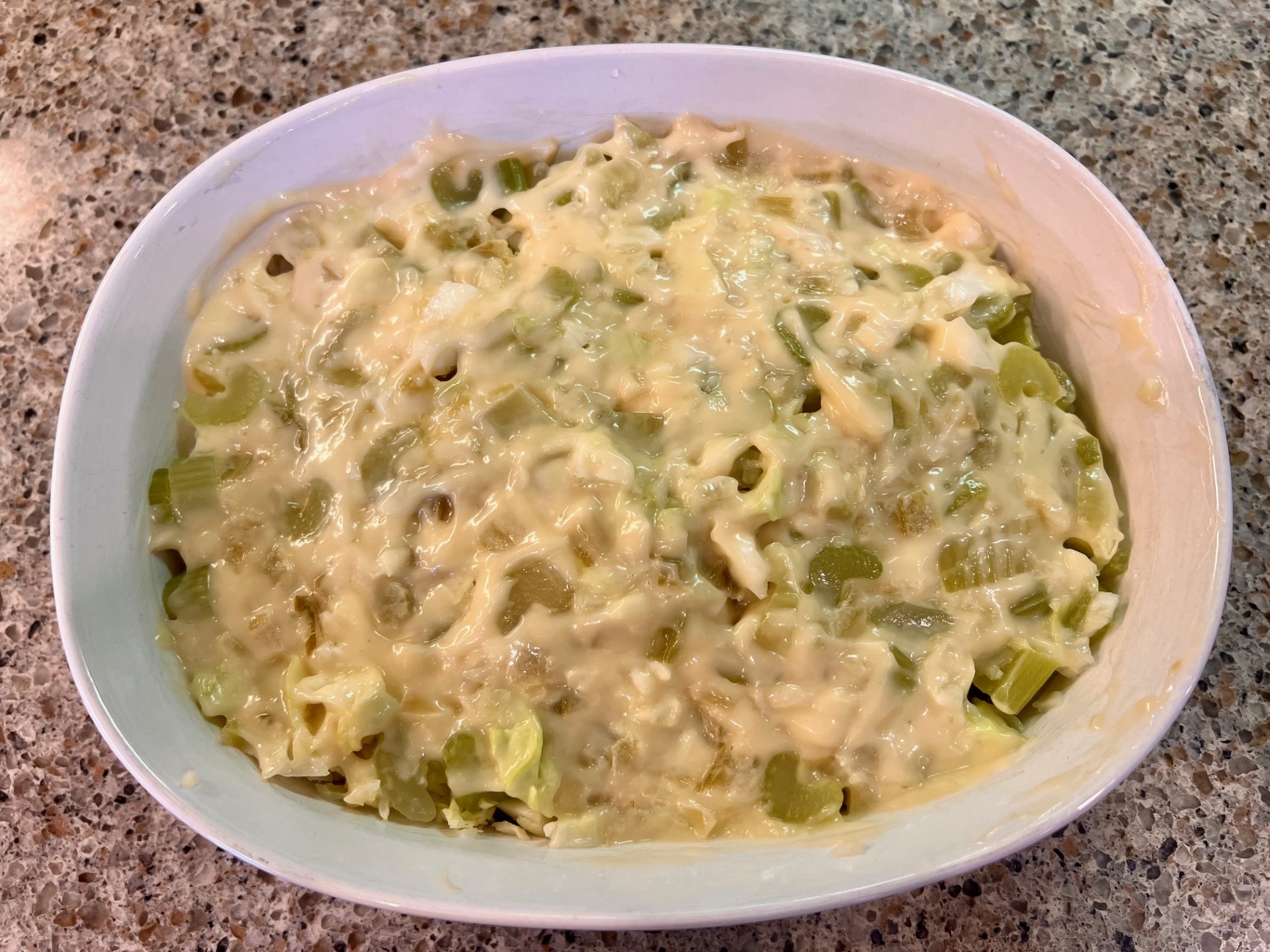

The first instructions are to “cook celery in small amount of water for 10 minutes. Drain, combine celery and cabbage.”

From this guidance, I inferred that only the celery should be cooked, and then combined with raw cabbage, and thus, I proceeded in this fashion. I wasn’t sure what a “small amount of water” meant to Ms. Brekke, nor whether it was to be boiling or merely warm. I decided to boil enough water to fill the bottom fourth of my wide saucepan, and then added the celery, draining it ten minutes later and mixing with the cabbage I chopped.

This casserole too was layered, but with all the vegetables on the bottom, with half a teaspoon of salt, and followed by two layers of the soup and cheese, and topped with “2 T. buttered, toasted bread crumbs” (a nice, not overwhelming amount). Though I didn’t have the recommended can of cream of chicken soup, I did have cream of celery (and now it remains a vegetarian dish).

But I was flummoxed by the cheese: “1/4 lb. of processed pimento cubed cheese.” What could this be? The adjective “cubed” implies firm cheese, rather than a mixture, like the beloved classic pimento cheese dip, or a cheese spread. Did Velveeta make a pimento cheese? They make one now with jalapeños. And I’ve seen other firm cheeses in the grocery store with olives, cranberries, and various peppers, but not pimentos. So I shredded four ounces of an extra sharp cheddar and added two heaping tablespoons of jarred pimentos.

Finally, I toasted the breadcrumbs on the stove, added butter, and sprinkled them on top of the cheese.

After 30 minutes in the oven at 350˚, the casserole reached 167-170˚, depending on where I checked it, and I again, turned on the broiler for about three minutes to deepen the golden color on top. When I set it on a trivet to cool, it had a beautiful bubbling cheese effect, reminiscent of baked pastas.

But when I cut into it to transfer it to a plate, it became clear that the bottom was full of liquid, released from the celery and cabbage as they cooked. And frankly, this dish tasted wet—a wet, unseasoned pile of boiled celery and cabbage. The cheese and soup layer at the bottom felt wet too—undoubtedly because of never having the opportunity to sink down and coat the vegetables. After draining the liquid and heating it to try to cook it further, I tried the casserole again, but it remained the same, pretty soggy.

I am eager to talk to Donna Brekke soon to learn more about the origin of this casserole and whether I have mis-stepped in my preparation at some point. Or perhaps this is like my mother’s contribution of microwaved liver slices—it’s certainly not a family favorite but rather an interesting recipe she came across at a moment when it was in vogue to use a new technology and thought others might be curious.

Boil Dem Cabbages Down!

This line from Too Busy Marco, a favorite picture book in our family, always made us laugh. The moment at which it is shared is homespun—Marco the parrot is playing a banjo and singing about cabbage.

And both of these hotdishes/casseroles are homespun, as all hotdishes are. Revised and updated by John Becker and Megan Scott, Irma S. Rombauer’s classic tome, Joy of Cooking notes that these dishes are perceived as outdated: “The popularity of casseroles—a diverse collection of mixtures named after the dish they are baked in—seems to have wanted in recent years. Despite being passe in some circles, casseroles are truly the foods of community and sharing” (531). Howard Mohr, the author of How to Talk Minnesotan: A Visitor’s Guide seconds this notion of sharing, as well as noting the classic casserole combination as main ingredient + cream sauce/soup, baked in one dish (13-14 and for more see “Hotdish vs. Casserole” in my previous post https://blog.cord.edu/karlaknutson/2023/07/04/hot-dish-horror-part-ii/).

So are these recipes mis-titled? Should they use “hotdish” in the title, given their location of origin? Is the first one scalloped? Or a cabbage casserole? Or a gratin? Maybe the answer depends on how you understand breadcrumbs to be involved in scalloping. While scalloped corn recipes (including the one just below it by Cora Michaelson) typically incorporate the crackers or bread crumbs into the mixture itself (undoubtedly the foundation of my slight surprise when I realized that I was to make a béchamel), the scalloped cabbage recipes I’ve discovered are all layered and topped with breadcrumbs, as well as cheese.

Previously, I did a deep dive into scalloping and its linguistic history (for more fun, see https://blog.cord.edu/karlaknutson/2024/01/19/scalloped-corn-holiday-side-dish-extraordinaire/). Based on that research, I can confidently say that according to the definition in The Dictionary of Food: International Food and Cooking Terms from A to Z, “to scallop” means “to cover with sauce and breadcrumbs and bake in a casserole.” So both of these cabbage dishes certainly could be called “scalloped cabbage.”

But it becomes more complicated, as we meander into the fine distinctions, which would address the presence of cheese and thus, more precisely label these dishes as gratins, a la the most famous version: potatoes au gratin. Joy of Cooking’s editors note that even this term, “with cheese,” is location-specific: “‘Au gratin’ is a term that, in America, is usually associated with cheese. But the term may refer to any topping of fine fresh or dry bread crumbs or even crushed cornflakes, cracker crumbs, or finely ground nuts on casseroles, creamed dishes, stuffed vegetables, or any dish where a browned, crispy upper crust is desire” (957).

And Joy of Cooking includes a “Cabbage Gratin” recipe, with a fascinating caveat: “While the words ‘decadent’ and ‘cabbage’ are not often found together, we make an exception for this dish” (225). Another delicious-sounding cabbage casserole recipe by Kay Rentschler is included in Amanda Hesser’s The Essential New York Times Cookbook: The Recipes of Record, called “Cabbage and Potato Gratin with Mustard Bread Crumbs.” Despite a lack of cheese, a similar version called “Baked Cabbage” appears in Fun Cookin’ Everyday, the North Dakota Association for Family & Community Education’s community cookbook published in 1996.

So are these gratins, but with boiled, rather than sautéed cabbages? They certainly stretch a an inexpensive piece of fresh produce into a large meal. And while cabbage has a long refrigerator shelf life, baking it may revive a head of cabbage that is close to having seen better days. And if meat is scarce, a vegetable casserole is a nice way to add heft to an otherwise light ingredient.

Contributor: Donna Brekke

There are three candidates for Donna Brekke from Velva, North Dakota, and none are mother and daughter. It’s not a “Berry,” “Berry Jr.” Berry Jr. Jr.” type of situation. Instead, one was born Donna Brekke but became Donna Caulkins upon marriage; another was born Donna Miller and became a Brekke upon marriage; and another was born Donna Burgess before becoming Donna Brekke upon marrying Daniel Brekke in 1968. As the latter Donna lived in Velva in 1985, she is the likely to be our contributor to The Joy of Sharing in 1985. And Donna Brekke Caulkins was her sister-in-law, the oldest child of Daniel and Clarice (Pfeilschiefter) Brekke.

The daughter of Paul and Evelyn (Mohagen) Burgess of Velva, Donna Burgess was born about 1948, one of three children. Her father bought the Iris Theater (1913 – circa 1950s) after returning from World War II, and later opened Burgess Chevrolet and Implement, retiring in 1976. Prior to retiring to Minot, Donna and Dan raised their children just outside of Velva, where Donna worked at Peoples State Bank, and Dan coached and taught health and physical education. He also taught most of Velva’s young people to drive, as our driver’s education instructor.

Donna’s other contributions to The Joy of Sharing include “Banana-Orange Frosty,” “A Favorite Recipe” (a poem offering spiritual guidance), “Brownies,” and “Strawberry Marshmallow Dessert.”

****A very deep and sincere thank you to Carolyn Olson and Cathy Knutson for their help in identifying the Donna Brekke involved in the cookbook!****

This post is part of an ongoing series in which I make and reflect on recipes and the people who contributed them to the 1985 Oak Valley Lutheran Church compiled cookbook, The Joy of Sharing.