Tater Tot Hotdish

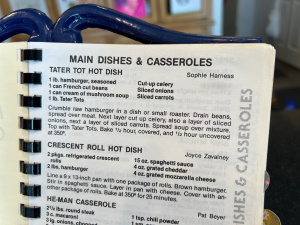

Because of the lukewarm reaction to the previous hotdish, I went looking for another one to make on Thursday for Gay’s family. Since we were out for our anniversary dinner on Wednesday evening, I didn’t have time to test another recipe. So I selected the first one listed in “Main Dishes & Casseroles,” the much-loved Midwestern favorite, “Tater Tot Hot Dish,” contributed by Sophie Harness.

This proved a mistake.

I should have known when the first instruction was to “crumble raw hamburger in a dish or small roaster.” It felt weird not to brown the beef, as I had in every single other tater-tot hotdish I’ve made in the past twenty-five years of my life. But I tried to trust the instructions, since that is one of the covenants between recipe writer and cook. As Kate Lebo explains in her reflections on the genre of the recipe, “ In any book of food, the details must be right. The authority must be deserved. . . . When the recipe writer fails, that failure becomes the reader’s failure, too.” Is a recipe a guarantee? Does the recipe writer or contributor owe something to the reader? If so, what? What must the reader/cook bring to the endeavor? Here, I brought my experience and knowledge, which contradicted the recipe facing me on the page.

So…what to do? In this case, I followed the instructions, as I was interested in whether this technique was something I didn’t but should know about. I decided to trust the authority of the book of food, because that earnestness, that trust, is what the form requires. When I’ve deviated with past recipes, it’s because I knew that I should deviate. Here, I did not know if there was something I didn’t know—since I’d never thought to not brown the ground beef before.

The recipe also indicated the “hamburger” should be seasoned, which confused me slightly—whether I should season it in the package, or after it was placed in the dish, as well as what seasoning entailed. Eventually, I spread out the ground beef in the pan and sprinkled it with kosher salt and pepper.

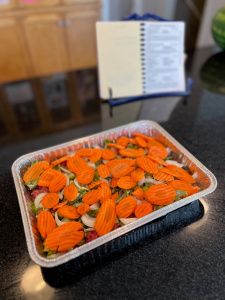

All seemed fine past that point, as I built layers of vegetables over the hamburger, first the green beans (frozen, not a can), celery, sliced onions, and sliced carrots. No measurements were indicated for any of the fresh veggies. I googled tater tot hotdish recipes with celery and onion; a recipe at Taste of Home’s website specified a half cup of onion and a third of a cup of celery; I placed sliced carrots on top (purchased the carrot chips to avoid extra work and because of the fun texture) until they appeared plentiful.

Next, I used a spatula to spread cream of mushroom soup over the layers of vegetables and began placing tater tots on top. While Sophie indicated a pound of tots, I ended up using approximately one and a half pounds to cover the dish I was using. While some recipes show these in neat rows, I like to see the tater tots in different positions, and so I pressed them into the soup to be touching, but not uniform.

The instructions indicated an hour of baking at 350 degrees, the first half covered, the second uncovered. At the hour mark, the casserole’s edges were just starting to bubble, and the internal temperature of the center was in the 150s. It baked for another 40 minutes before being warm enough to eat. I dropped it off with Gay, accompanied by a salad and loaf of French peasant bread.

While this pan baked, I decided to make a second casserole so that I could try it too. I followed the same steps, except that I decided to use cream of celery soup because I like the slight change that offers in flavor, as well as the yellow color.

We had an activity that night, and so I put it in the fridge to wait until the next night, when Claire had dance. Since it was cold from the fridge and the other pan needed significantly more time, I knew it would be fine to have it cook for a while. When we returned home from dance, I checked the temperature, and the centered showed 175-190 degrees, in various spots. The edges showed over 200 degrees. I made a quick salad, Luke made a new, delicious cocktail called a Champs-Élysées, and we sat down at our patio table on a calm evening.

Reflections

It looked beautiful, and I appreciated the layers of vegetables in different colors. However, Luke and Claire both had the same first note: too many vegetables! I didn’t pay any attention to them; those two are just wrong about the balance of vegetables in all meals. It’s a refrain in our house. But I was just starting to think that it could use some salt and pepper, particularly on the ground beef, when I turned over a chunk of beef and realized that it was fairly pink. I started stirring mine around and saw more pink, and Luke and Claire did the same, with the same result.

We’re not squeamish about food—we eat sushi (actual sushi, not just California rolls—Claire’s favorite is salmon nigiri), raw oysters fresh from the ocean on the beach in Mexico, beef carpaccio, no steak cooked past medium rare…all the good things! Luke and I have enjoyed many juicy, medium-rare hamburgers from nice restaurants where they grind their own ground beef, making it safe to be cooked to a lower temperature. But not in a tater tot hotdish. This was a surprise that changed the course of the meal. We picked at our salads and our tater tots and headed inside, still hungry.

After Claire was in bed, Luke stopped by my writing desk and said, “I think I need a Whopper or something, but I also think I might be off hamburger for tonight.” I said, “I feel a bit sick.”

So that was a fun evening.

I was mortified that I had made this and delivered it to Gay and her family. Luckily, she said that hers was completely done; I had already advised her to put it in the oven to reheat. Whew! Her young daughter’s notes were “It’s actually quite good!” Crisis averted, it seems.

However, my family’s good-will has been squandered. They are refusing to eat any casseroles for a while, and I don’t really blame them. I was frustrated about the way this hotdish turned out; it felt like a waste of time, money, and food. I wonder if the pan I sent to Gay’s house, which was a thinner disposable roaster so that she wouldn’t have to worry about returning anything to me, made a difference; I started with a cold Corningware casserole dish from the fridge. So maybe it’s my fault.

To be sure that my oven was hitting the right temperature, I checked it with a Thermapen probe set to a low of 330 degrees and a high of 380 degrees. It stayed right between 350 and 380 during the entire time I cooked a rhubarb crunch in an attempt to regain their interest. The Thermapen is the most wonderful product—we have a few different types, and I use the Thermapen One probe every single day. It’s also fun for travel; in Iceland, I took many photos of Luke checking the temperature of hot springs, rivers, and just steaming earth. It’s an amazing instrument.

It remains troubling to me that the beef wasn’t browned first, and I think that is the culprit. In a quick, not exhaustive search for tater tot hotdish recipes online, I could find only one other recipe that did not brown the beef first. And “8 Tips for Making the Perfect Casserole” on Martha Stewart’s website reminds us in a wonderfully imperative style to “Always Cook Meat Before Adding. Don’t add raw meat to a casserole” (Ormont Blumberg),for exactly the two reasons I was concerned about: 1) safety, if the meat does not reach its required minimum temperature; and 2) grease, if it was in need of draining: https://www.marthastewart.com/8196775/how-make-casserole-tips. If ever there was an appropriate use of the imperative, this is it! Don’t use raw ground beef in your tater tot hotdish!

Hotdish vs. Casserole

“Hotdish” and “casserole” often are used interchangeably; however, as Howard Mohr explains in How to Talk Minnesotan: A Visitor’s Guide, “hotdish is cooked and served hot in a single baking dish and commonly appears at family reunions and church suppers. Hotdish is constructed on a base of canned cream of mushroom soup and canned vegetables. The other ingredients are as varied as the Minnesota landscape” (13). Its importance is underscored by its location in this book, as the first topic covered in the third chapter, “Eating In in Minnesota.” Mohr’s recipe for a generic hotdish lists the three key ingredients as “two cans cream of mushroom soup, 1 pound cooked pulverized meat, 2 cans of vegetables” (14). Note—the meat is cooked before it is mixed together and baked. The same instruction can be found elsewhere: Nicole Hvidsten, the taste editor for the Star Tribune, describes the first step in the “blueprint” for tater tot hotdish as browning ground beef: https://www.columbian.com/news/2022/aug/17/tater-tot-hot-dish-isnt-just-for-minnesotans/.

The Northern Plains/Northern Midwest prefers the term “hotdish” over casserole. In an article on Eater, one of my favorite food websites, particularly for restaurant recommendations when traveling, Lina Tran points to MN and ND as the hotbed for hotdish: “Hotdish is an anything goes one-dish meal from the Upper Midwest, but it’s especially beloved in Minnesota and North Dakota” (https://www.eater.com/2016/5/15/11611558/what-is-hotdish). All of the sources I’ve cited here, as well as a documentary called Minnesota Hotdish: A Love Story (https://vimeo.com/65158243) and “How Tater Tot Hotdish Became a Minnesota Classic” (https://www.americastestkitchen.com/cookscountry/articles/7045-in-the-library-with-toni-tipton-martin-how-tater-tot-hot-dish-became-a-minnesota-classic) point to a 1930s cookbook, the Grace Lutheran Ladies Aid Cookbook from Mankato as including the first published recipe for hotdish, submitted by Mrs. C.W. Anderson; they also discuss how hotdish developed during the Great Depression as an economical dish that stretched a small amount of protein.

Hotdish has become central to the identity of Minnesota. Its congressional delegation has engaged in a hotdish competition since 2010; an overview of this competition actually is the featured culinary note describing Minnesota in Gastro Obscura: A Food Adventurer’s Guide, a fascinating book covering unique foodways in cultures across the world. And a tater tot hotdish in a pan shaped like Minnesota is what graces the cover of Patrice M. Johnson’s Land of 10,000 Plates: Stories and Recipes from Minnesota. I haven’t found anything about its centrality to the psyche of North Dakotans in popular culture yet, but there’s just much less written about and by North Dakotans. There aren’t as many of us. So I’m writing it, starting with this post. It’s always been my favorite hotdish.

It’s interesting that this is the only tater tot hotdish included in a community cookbook from the mid-1980s, a cookbook with many multiples: four krumkake recipes (Thelma Lysne, Eunice Ragazinskas, Gladys Kantrude, and Irene Grunseth), two hamburger pies (Martha Knutson—my paternal grandmother and Cindy Culbertson), two calico beans (Virginia Feist and Helga Haga), and eight versions of sugar cookies (Agnes Chilson, Diane Pfeilschiefter, Frieda Sandberg, Mrs. Floyd Anderson, Louise Roebuck, Phyllis Blohm, H. Hammer, Judy Anderson, and Myrtle Wright). Given its ubiquity in North Dakota and Minnesota, it makes sense that it takes pride of place as the first recipe listed in the “Main Dishes & Casseroles” section (similar to the larger category of “hotdish” being the first local food discussed in How to Talk Minnesotan). But it’s surprising that this recipe is the only submission—perhaps it is too well-known? It doesn’t need to be explicitly articulated because we could all make it in our sleep? This raw-ground beef version was enough of a variation to be included? I’m eager to ask about it.

Contributor

Sophie Ingeborg (Zachariason) Harness was born in 1903 in Minnesota. Her husband, Theodore R. Harness, or Ted, as he was known, was born in 1899 in Lake Park, Minnesota, a town east of Moorhead, MN. In 1902, he moved with his parents Otilda and Ole Harness to their homestead north of Velva. After meeting when Ted visited Minnesota in 1922, the couple married in 1923, and had two children, Marcella and Bonnie. After farming in Minnesota, they moved to Velva in 1937, and in 1947, they purchased the Sigman farm and part of E. Byerly place, farming until 1974, and then retiring to Velva. Sophie passed away at the age of 100, in 2003; Ted, in 1988. She contributed two other recipes to The Joy of Sharing: “Bread Pudding” and “Lemon Fruit Salad.”

This post is part of an ongoing series in which I make and reflect on recipes and the people who contributed them to the 1985 Oak Valley Lutheran Church compiled cookbook, The Joy of Sharing.