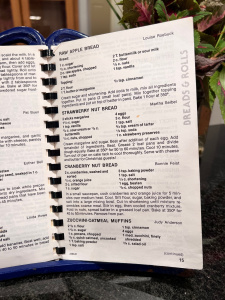

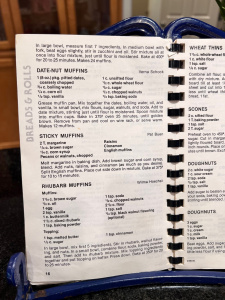

July in North Dakota means that zucchinis are starting to be left on doorsteps all across the state (soon corn will follow). And as a parent, I’m always looking for more ways to deliver as many vegetables as I can. So I made Judy Anderson’s “Zucchini-Oatmeal Muffins” from the “Breads & Rolls” category.

Preparation

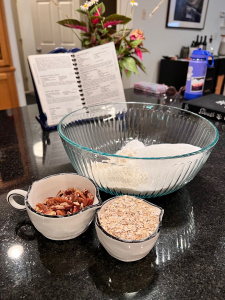

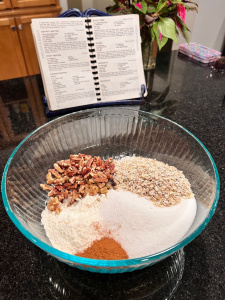

This was another easy-to-follow recipe, with no moments wondering what to do or what something was. Also, this uses “whole food” ingredients I want my child to eat—eggs, zucchini, nuts, oatmeal. As I started mixing it up, I realized that I only had about two-thirds of the required cup of pecans, but I improvised, substituting one third of a cup of walnuts.

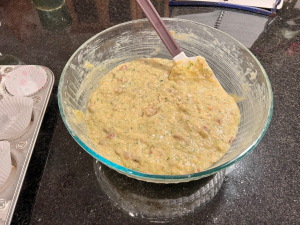

This made lots of attractive batter, with pretty, green whisps of grated zucchini.

It was clear that Judy Anderson knows something about baking—she warns the baker not to overstir the combined mixture of wet and dry ingredients, which is a hallmark of making quick breads and batter breads. In On Food and Cooking: The Science and Lore of the Kitchen, Harold McGee explains why this is the case: “Quickbreads are appropriately named in two ways: they are quick to prepare, being leavened with rapid-acting chemicals and mixed briefly to minimize gluten development; and they should be quickly eaten, because they stale rapidly” (549). And while Betty Crocker’s Cookbook aka The Big Red Cookbook classifies muffins, coffee cakes, popovers, biscuits, scones, pancakes, waffles, and French toast all as quickbreads, McGee further distinguishes amongst these types, placing biscuits, biscotti, and scones into the category of quickbreads and creating discrete categories for “thin batter foods,” like popovers, griddle cakes, and crêpes, and for “thick batter foods,” such as batter breads, muffins, and cakes (550-554). McGee clarifies the differences between thick batter foods and quickbreads:

Batter breads and muffins are moister, usually sweeter versions of quickbreads. They’re leavened with baking powder or soda, and often contain moderate amounts of egg and fat in addition to sugar. . . . Muffin batters generally contain less sugar, eggs, and fat than quickbreads. The ingredients are mixed together just enough [emphasis mine] to dampen the solids, and the mix baked in small portions rather than a large loaf. Well-made muffins have an even, open, tender interior. . . . Overmixing produces a less tender, finer interior with occasional coarse tunnels, which develop when the overly elastic batter traps the leavening gas in large pockets. (554)

However, this information isn’t exclusively available to those interested in food science or after the publication of McGee’s first edition in 1984. Betty Crocker offers this warning too, at least in my copy of the ninth edition, published in 2000 (and presumably in the previous eight editions as well as in the four published since then: “If you mix quick breads too much, they become tough” (45).

So, if you encounter a tough pancake, biscuit, or muffin, it’s likely that its creator is an over-zealous mixer.

When I began spooning the batter into the muffin pans, I filled each only slightly, and then added a few chocolate chips to most, but not all, of the muffins, before covering them with more batter and a few chocolate chips on the top. My goal was to entice my daughter to eat zucchini muffins, as well as to add a bit more gooeyness from a warm muffin with melted chocolate.

After twenty minutes at 400 degrees, they looked just about ready to be removed from the oven, but I thought a couple could be slightly more golden. I waited two more minutes to retrieve them. Depending on how full the cup is, some muffins and cupcakes do not rise fully; I was impressed to see that the ample batter led to multiple muffins with great height, a beautiful golden-brown color, and symmetrical round top.

Tasting Reflections

In the morning, the Baby tried one and pronounced it “okay. It’s too chewy—you can taste the oatmeal.”

Okay.

But she liked them enough to bring two to her teacher at theater camp as a gift for the teacher’s birthday. So that’s a win.

I brought muffins to my campus office right after that, and my taste-testing friend/colleague said they were good. I thought they were not as moist as I hoped they be (maybe that last interval in the oven is the culprit?), but he said I was wrong.

So who knows?

That afternoon I decided to make some decaf (decaf is strange for me, but I craved warm coffee after writing outside all afternoon on a windy day), warm up a muffin, and do a warm taste test.

It turns out everyone was right. With fifteen seconds of heat and some Kerrygold butter, what I thought was a not-super-moist but nice-tasting muffin was now chewy and moist. I want to try these again, without the extra two minutes in the oven, and see how they fare.

Also, I was charmed by the chance to engage in a traditional regional ritual, the afternoon lunch.

Lunch

Lunch is apparently slightly different in Minnesota, according to Howard Mohr in How to Talk Minnesotan. Mohr mentions three lunches: the first is before breakfast, the second is at 10:00 am, before the noon meal—beware chastisement and derision if you dare to call this meal anything but “dinner,”—and the third is between 3:00 and 3:30 pm, prior to the evening meal (16), strictly known as “supper.” Mohr also defines “a little lunch,” noting that it is the designation for lunch “at other odd times of the day” (17). Regular lunch includes “a drink—coffee, punch, or Kool-Aid—and a large tray of meat sandwiches on snack buns, fresh-baked cinnamon rolls, and several varieties of the native dessert called bars” (16).

When I was growing up, lunch commenced at 4:00 pm every day but Sunday (though less regularly during the winter) at my great-aunts’ and great-uncles’ house, at their farm on the quarter west of my farm. Lunch comprised some sweets, maybe cake donuts if someone had been to town recently, store-bought and homemade cookies, and sometimes spray cheese on crackers, or fruit. But it always included coffee, and for my Great-Uncle Edwin, sugar cubes in that coffee. What a magical, shimmering square that sugar cube was to a child! I was obsessed with them, always asking for one of my own to hold, even if I didn’t have a warm beverage requiring their sweetness.

During the summer, lunch became a bigger meal for the farmers, with sandwiches and larger portions of all the other components, as well as additional dishes like chocolate cake, Coke, chips, and in more modern times, e.g. the 1990s, yogurt for those on a health kick. At this time of year, lunch might take place in the farmhouse or out in the field. Still triggered by the smell of orange peels, some of my happiest childhood memories are delivering lunches with my mom and sister out to “the Guys,” bumping down the prairie road to wherever the equipment was stopped for the break and goofing around with them until they had to start up again.

Contributor: Judy Anderson

Judy Anderson was born Judith Resler in 1943, to John and Pearle Resler of Upham, ND, a small town forty-five miles north and just slightly east of Velva. After high school in Upham and the North Dakota School of Forestry in Bottineau, she earned a degree in social work from UND in 1965. That same year, Judy married Donald Anderson, of Nome, ND, and later LaMoure, ND, born in 1936 to Theodore and Ellen Anderson. Judy’s work in Velva was as a social service consultant for the Souris Valley Care Center, and she was active in the Velva Women’s Club, as well as at Oak Valley in the A.L.C.W. and as assistant Sunday school superintendent. Don received a degree in industrial arts education from Ellendale State Teachers College in 1965, and taught and coached for fourteen years in various schools, including Sawyer, five miles from Velva. He then turned to a career in industry, as a welding inspector at the Coal Gasification Plant in Beulah and later as a civil engineering technician in Harvey and Bismarck before retiring in 2001. The couple has two children, Jodi and Brian and several grandchildren. Don passed in 2016, and Judy still lives in Minot, ND. When I asked her about Judy, my mother said that Judy and Don moved to Velva and become immediately and usefully involved in the community and church. She mentioned that their daughter Jodi was a wonderful singer, someone talented enough to sing at her own wedding—with great success, in fact, as my mother attended the wedding; Mom said the Andersons were such a pleasant family. Judy’s other recipes in The Joy of Sharing include “Sugar Cookies,” “Sweet & Sour Chicken,” and “Mint Dazzler.”

Who doesn’t want to be dazzled? That sounds like a winning recipe.

This post is part of an ongoing series in which I make and reflect on recipes and the people who contributed them to the 1985 Oak Valley Lutheran Church compiled cookbook, The Joy of Sharing.

So interesting to read about Judy and her family history. I have fond memories of Judy! It’s a nice addition to the recipe to know it’s creator.