My posting frequency has been a bit uneven lately—with a gap of several days prior to many posts in a row.

Well, we were on vacation! And now that we’re back, I want to share a bit about what we ate in Montreal.

Since we knew I’d be cooking all summer from one cookbook representing one region, we headed to Montreal because it’s known as one of the most amazing food cities in the world. We were ready to eat French food, and we did. We really did.

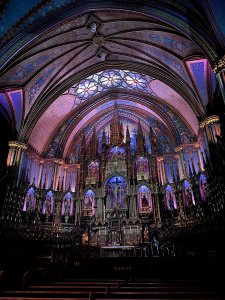

I mean, we did other things too, like kayaking on the Lachine Canal down to Old Port, attending the Aura Experience (an illuminated light and music show–it’s phenomenal) at the Notre Dame Basilica of Montreal (https://www.aurabasiliquemontreal.com/en/experience), twice riding La Grand Roue (their “observation” wheel)—midday and after dark—and visiting the botanical garden, art museums and galleries, and the children’s science and technology museum for a wonderful almost-five-hour extravaganza of fun: https://www.montrealsciencecentre.com/exhibitions. What a quintessentially Canadian experience—the featured exhibition is on the science of hockey, the first thing you see is a Zamboni, and the sponsor is Tim Hortons! We also headed into the Laurentians and Outaouais to experience the mountains and countryside (Parc Omega! Wineries! Lavender fields! Gondolas and luges in Mont Tremblant! Amazing fun!).

But exploratory eating was a priority, as was not doing dishes.

Here are some of our favorites:

Tommy Café:

On our first morning, we headed straight to Tommy Café, Claire’s dream breakfast since watching a YouTube video about the best things to do and eat in Montreal. It was as magical as she imagined! Luke and I had some of the gorgeous avocado toast options, and Claire had “Ton Smores,” the most sugary, chocolatey, gooey way to deliver French toast—yes, that is topped with graham crackers, marshmallows, and Nutella! She clearly did not finish it.

The only word to describe their coffee is “velvety.” We tried cappuccinos, café au laits, Americanos, and hot chocolates during our many visits.

We went back every morning we were in Montreal—sometimes just for pastries, sometimes for toast, sometimes just for coffee. Also, I’m obsessed with their hanging plants.

Place Carmin

Eater lists Place Carmin as one of the thirty-eight essential restaurants in Montreal right now (https://www.eater.com/maps/best-restaurants-montreal-quebec-canada), and since it was near our apartment in the Old Town and looked elegant, we booked a reservation at this French brasserie for our first night in Montreal. It was superb in every way! Some of our favorite dishes were the beef tartare, the pork filet, sea bream (incredible!), as well as the strawberry shortcake and Paris Brest for dessert, from their award-winning pastry chef Léa Godin Beauchemin.

Amazing cocktails, mocktails, and Québécois wine too! We had a lovely evening on their terrace.

Snowdon Deli

Truly a treasure trove, the same Eater article offered a perfect option when Luke said, “I want to try the famous Montreal smoked meat, but I don’t want to stand in that long line with other tourists at Schwartz’s Deli.” Ever the researcher, I was prepared with a suggestion: Snowdon Deli. Eater describes its appeal perfectly:

Looking for famed Montreal smoked meat without having to endure the snaking queues? Family-owned Snowdon Deli is a circa-1942 deli that offers the city’s iconic smoked meat on mustard-smothered rye in addition to matzo ball soup, chopped liver, latkes, knishes, and blintzes — minus the wait time. Inside, expect a no-frills atmosphere where regulars squeeze into booths, chatter flows from behind the deli counter, and veteran employees ensure everything goes off without a hitch.

This was one of the highlights of our trip, and certainly of our day, sandwiched between the Montreal Museum of Art and the Botanical Gardens (our afternoon at the gardens was hotter than we realized it would be—maybe we shouldn’t travel in summer and sit in the pool instead? Food for thought…). We ordered a bunch of things to share, and wow, our meal did not disappoint: karnatzel, pate with onions, meatballs in a rich tomato sauce, table fries, and smoked meat sandwiches with mustard. Luke commemorated his excellent meal and euphoria with an amazing t-shirt.

Wilensky’s Light Lunch

This charming restaurant has been open since 1932 for a “light lunch” at the counter or in your hand as you walk onward. It has a wonderfully curated menu: http://www.top2000.ca/wilenskys/ENG_TABLE_Menu.htm. We tried Wilensky’s specials with cheese, a side of pickles, and egg crème sodas all around! Claire had chocolate; Luke, orange; Karla, pineapple.

Claire enjoyed this so much we headed back two days later. She had a hot dog this time, I had a chopped egg sandwich, and Luke polished off two Wilensky’s specials, one with cheddar, one with swiss. Luke stuck with the glorious orange egg cream soda; Claire, a chocolate milkshake (made with milk, not ice cream); and Karla, a lemon-lime old fashioned soda.

And we met the woman pictured on the website. This place is a gem, and we think of it fondly whenever Luke wears his new Wilensky’s hat.

The Great Bagel Debate: Fairmount or St. Viateur?

Montrealers take their bagels seriously. And they are serious about which of the two institutions has the best bagel in Montreal. We tried both, but I’m not sure we have a favorite; both were delicious. As we ate some fresh and some the next morning, it wouldn’t be a fair competition anyway. But really, they were both amazing, as are their signage and logos. We tried a plain, sesame seed, poppy seed, and onion at Fairmount, eating them on a bench on a sidewalk and dipping into a container of cream cheese. So fresh, light, and delicious! Since St. Viateur is a few blocks away, we picked up a pumpernickel, sesame seed, and plain bagel for breakfast, as well as an amazing t-shirt and tote bag.

Dobe and Andy Restaurant

After Claire’s marathon session at the Science Center, we headed to Chinatown for an amazing lunch at Dobe and Andy Restaurant. Since it describes itself as a Hong Kong-style barbeque, we had roasted meat—pork loin, pork belly, and duck, with rice, noodles, and some amazing wontons to start. Three bites into her meal, Claire said, “I think this is the best meal we’ve had in Montreal.” And we’d already been to all the places I’ve mentioned. That’s pretty high praise, given her love for Wilensky’s.

After we finished, we walked around to find pastries, a perennial favorite Chinatown treat for me and Luke—we’ve had them in New York, Chicago, San Francisco, and now Montreal. And on Claire’s first visit to a Chinatown, she found them delightful too! This time we got pineapple buns with and without cream and a coffee bun, to go with our coffee and milk tea. Yum…these are always such a treat.

And the inimitable Joe Beef…

If you like food and are a carnivore (or at least an omnivore), you can’t go to Montreal and not dine at Joe Beef. In fact, meat-eaters might not have really visited Montreal if they haven’t. This is one of the most famous French restaurants in Montreal, always visited by food writers and food travel shows, and we remember watching Anthony Bourdain visit here years ago. We had to do it ourselves. I placed the reservation back in April, and Saturday night in late July was already full. But we were able to book a table for the next night they were open, Tuesday—our last night in Montreal.

And it was splendid. Stunning. And just damn fun.

Claire wasn’t sure at first what she would eat and was a bit sad, but as they brought out some starters, sashimi and a fois gras cake with her mocktail, an “Orange Cooler,” she fell in love.

And more continued to appear and enchant her—a hanger steak and the world’s best fries, with truffle oil and garlic snapes; one of the night’s specials—a New York strip au poivre, and a guinea fowl. Luke and I had cocktails—his was called a “Monkey Gland”—and an incredible Québécois red wine.

And after that sharable feast, dessert. The most decadent eclair and the perfect Canadian spin on beignets—drizzled with maple syrup and flakes of gouda. It was heaven.

We had a blast talking with our servers, who were delighted by what interested Claire’s palate, and with our neighbors—we recognized one table from our kayaking adventure that morning—and we met the folks at another table—an Australian barbeque master named Brad and his family, who all traveled to Montreal for their comedy festival after a three-week barbeque trip to Texas (twenty-one barbeque meals in twenty-one days). He showed us pictures of him with Tootsie Tomanetz, the first chef featured in “Episode One” of Chef’s Table: BBQ, and with Aaron Franklin, of Franklin Barbeque in Austin (I’m indebted to him for the excellent steak grilled at my house).

It was an amazing night. No Tommy Café the next morning—we were still too full.

Au Moulin Du Temps

And in the countryside, I have to mention the fun of Au Moulin Du Temps, a small roadside restaurant with some killer pizza. And yes, that is a pitcher of Budweiser. While we like to drink, eat, and shop local when traveling, this was the only beer on tap. Lager was light, cool, and refreshing with our pizza and Greek salad after a warm and dusty day exploring Parc Omega. It was perfect.

Reflections On Eating and Drinking, In and Out

When we were in the Québécois countryside, we did more cooking, which was fun because it’s always fascinating to go to the grocery store in a different country and see what is available. But that meant we did more cleaning up, which is the absolute worst. And one of the things I value most in a vacation is a break from cleaning up and doing dishes. I’m intentionally paying for the privilege of not cooking and cleaning up (it’s one of the reasons that all-inclusive vacations skyrocketed in popularity after the pandemic—people were so sick of preparing, cooking, and cleaning up meals. It’s also why the food at many all-inclusive resorts is increasing in quality: see, among others, https://thepointsguy.com/guide/all-inclusives-on-the-rise/ and https://www.cbsnews.com/news/all-inclusive-leisure-travel-hotels-resorts/).

But here I was again, doing dishes.

It made me reflect on my summer of increased cooking and consequently, increased cleaning up. I knew this would be the case, but when you’re flipping through a cookbook, getting excited about possibilities, you don’t necessarily think of the accompanying clean up. You’re in the midst of imagining flavors and colors and smells! But I’m tired of doing dishes. And I was tired of doing dishes long before this summer—it’s just that there are more dishes to do now, since I’m making appetizers, fun beverages, breads, sweets, and treats. It’s been more work. More work of the particular type that I particularly detest. I hate doing dishes more than any other household chore.

Cooking and doing dishes while ostensibly on a break from doing dishes (that’s the problem with an apartment or house rental–you can save money by shopping and cooking and you get more space, but you create more work for yourself) also led me to reflect on the invisibility and visibility of these different, yet related forms of domestic labor. And it reminded me of a brunch Luke arranged a few years ago on a Saturday morning.

This particular Saturday was the first Saturday of a new semester, which is not a great time for a professor. While academics are very busy throughout the entire academic year, the two periods that most resemble an accountant’s tax season are the beginning and the end of the semester. So I wasn’t super thrilled to host anyone on that Saturday morning because at the start of a semester, I will neglect other household tasks, like straightening clutter, doing dishes, vacuuming, laundering clothes, and so on, until there is a bit of breathing room.

But given that this had been arranged and there was no getting out of it, it seemed, we managed to get some things straightened up on Friday night and then we decided I would continue cleaning Saturday morning, while Luke focused on cooking, a task he prefers and enjoys. Other than cooking, I did everything else involved in hosting, including washing the dishes Luke used while cooking and setting the table.

When we finished eating, our two guests turned to Luke, exclaimed over how good his cooking tasted, and addressed him by name to thank him for brunch.

Then there was silence. Their eyes looked down, up, around—anywhere other than at me. Nothing I had done to make their visit possible was visible to them. Nor was the inconvenient timing of their visit acknowledged.

In some ways, that makes sense, right? If you only go to someone’s home when it’s clean, when it’s an occasion, then you might assume it always looks like that. But does anyone’s home always look like that? Other than my Grandma Martha’s?

Cooking is visible labor—there is a product at the end of the process, one that others can experience: they see, taste, feel, touch, smell, and evaluate what has been cooked. Depending on where the cooking and eating take place, cooking becomes less visible and more easily ignored, of course. That’s why people may not tip when they aren’t faced with the person who did the work—it’s easier to pretend that no work has been done when they didn’t see it (and also why tipping is in the news right now—there are so many fascinating articles recently about the pressure to tip in situations that didn’t used to require tipping, because of the way that Square and other payment programs are set up to prompt tips (see, for example, https://www.npr.org/2023/07/05/1185160295/tipping-coffee-consumer-spending-inflation-tips and https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2023/01/technology-pandemic-economy-gratuity-tipping-etiquette-square/672658/). That’s also what is so interesting about a restaurant with an open kitchen—we see chefs at work—the physical structure reminds us that cooking is labor but also an art. It is something to interpret and commend. That’s what has been so fun about this project—the cooking is productive and creative and extends beyond my kitchen and my dining room and patio tables.

But cleaning is invisible. It only becomes visible if it hasn’t been done, not done well, or is obvious at the end of a party. The same is true of the preparation to cook—the cleaning up and making space for the cooking is invisible—it occurs prior to the presentation of the product. And it is also true of the preparation to host that happens outside of the kitchen.

We don’t do this work only when we have company. Everyone prepares food, does dishes, and cleans up each time we eat at home or pack a meal to take somewhere else. This happens multiple times a day; it’s relentless. It’s one of the worst parts of adulting. The relentlessness of this work has consequences if one person in a multiple-person household becomes primarily responsible for it. Widely reported in the popular press, a study published in Socius in 2018 by Daniel Carlson, Amanda Jayne Miller, and Sharon Sassler pointed to dishwashing as the chore most likely to affect relationship quality: “The equal sharing of housework is more positively related to sexual intimacy and relationship satisfaction among more recent cohorts and more negatively related to marital discord. The division of dishwashing, among all tasks, is most consequential to relationship quality, especially for women” (https://journals-sagepub-com.cordproxy.mnpals.net/doi/epub/10.1177/2378023118765867).

In an interview with Tove Danovich at NPR, one of the study’s authors, Carlson, explains that household tasks vary “‘in qualities: how pleasurable or unpleasurable, how often it needs to be done, how gendered it is.’” And dishwashing is gendered female in the United States, is not pleasurable, and must occur frequently, as Danovich notes:

While other household cleaning can be broken up over time, people have to eat multiple times a day, every day. Preparing meals is time-consuming, yet it also comes with a certain household celebrity — it’s a skill that people are proud to do well [emphasis mine]. “Dishes are a thankless job,” says Carlson. “It’s one of those things people resent having to do.” Unlike vacuuming, which is a task that addresses the combined mess of all members of a household, dishes are often dirtied by one person — and it’s easy to see who is the culprit. The shirker will pile them in the sink or take just one glass from the dishwasher, leaving the rest of the unloading for someone else. (https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2018/05/18/611978514/why-the-cant-he-wash-the-dishes-the-chores-that-can-sink-a-relationship)

And historically, American women have been expected to do food preparation and cleaning in so many households (obviously this varies by household structure and size, by socioeconomic status, and by race and ethnicity). Overwhelmingly, women in the US still do this work—see the 2022 chart for “Average Hours Per Day Spent in Selected Household Activities” published by the US Bureau of Labor Statistics: https://www.bls.gov/charts/american-time-use/activity-by-hldh.htm. Part of the reaction of our brunch guests reflects their sense that I failed my duties as the woman in a heterosexual marriage. They’re wondering—why didn’t Karla cook? Why didn’t she do anything? Why was Luke the only one working?

The actual questions are different: why was I the one doing the invisible tasks?

And why couldn’t they see that work as a contribution?

I have some ideas. But that’s a future essay on mental load, gendered division of labor, entitlement to focus, cooking as creative leisure, and so on.

***

I also keep thinking about the women who contributed to The Joy of Sharing, about how rare it was to eat out in 1980s rural North Dakota, yet how often food needed to be served. I think about how much else needed to be done every single day, particularly for some of the older contributors who did much of their domestic labor on farms and without some of the efficiencies we have now—electricity and refrigeration, dishwashers, sprinkler systems, washers and dryers, vehicles, and easy access to take-out and pre-made foods in markets. These amenities have all made housework a bit easier.

I have enjoyed cooking so often this summer, but I have not enjoyed the extra labor cooking necessitates.

Whether at a restaurant or in a home, having food put in front of you is such a privilege.

Vacations put that privilege in front of me, in stark relief.

This post is part of an ongoing series in which I make and reflect on recipes and the people who contributed them to the 1985 Oak Valley Lutheran Church compiled cookbook, The Joy of Sharing.