Scalloped Corn: Holiday Side-Dish Extraordinaire!

It’s not a Thanksgiving meal without scalloped corn or some sort of corn casserole, in my humble opinion. I’ve tried variations of this dish over the years, some with cheese, some with cornmeal or corn muffin mix, some with sour cream, some with whole-kernel corn rather than creamed corn. But I return again and again to the tried-and-true combination of crushed saltines, creamed corn, butter, and eggs, and I am rarely disappointed.

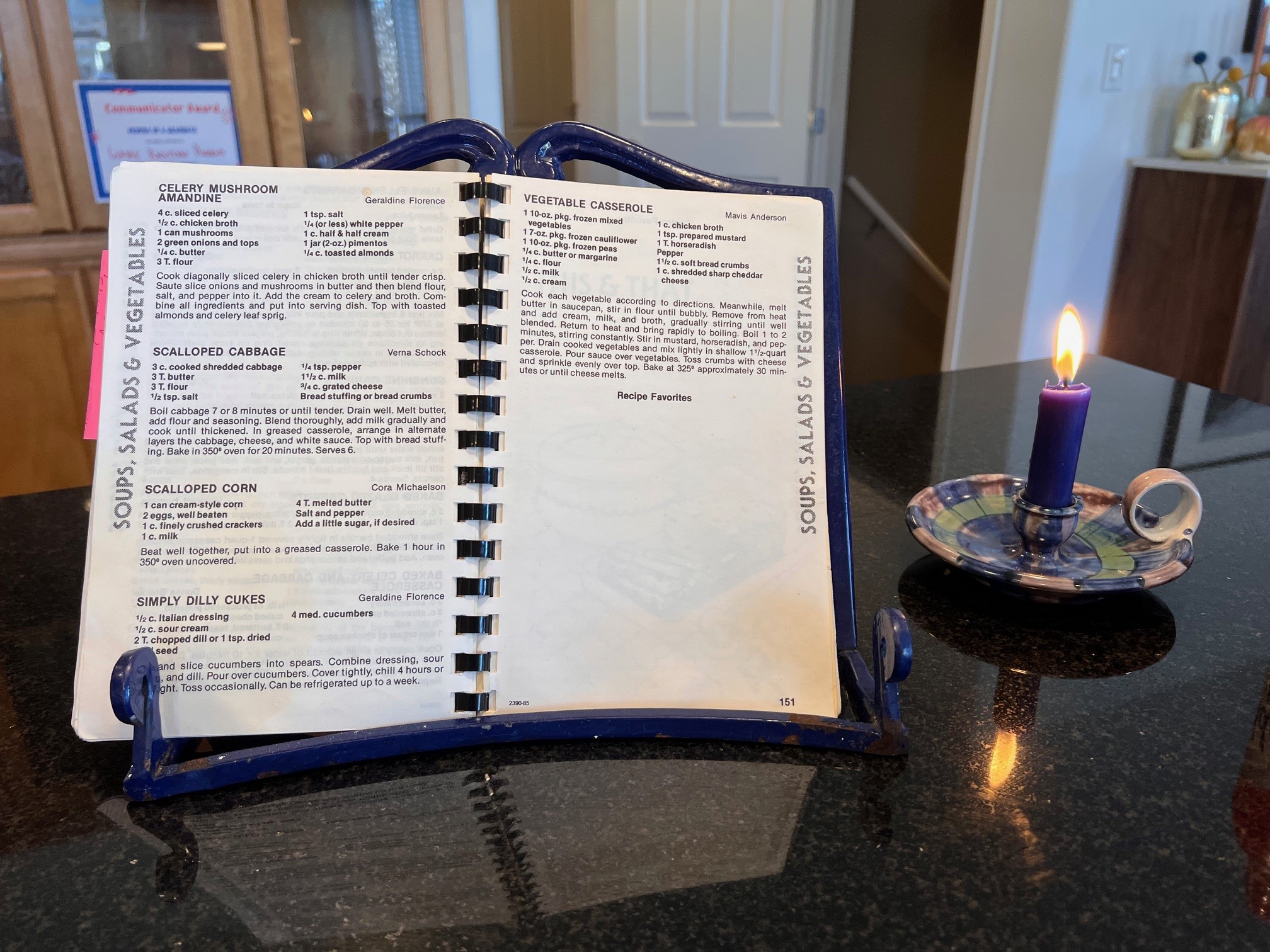

This year, I made Cora Michaelson’s “Scalloped Corn” recipe for both Thanksgiving and Christmas, and it was delightful.

Process

This recipe is simple and fast, which is a blessing on a holiday and to people like me, who always underestimate how much time it will take to do anything. On Thanksgiving morning, I made my other side dishes first, and began mixing this as our families arrived, an hour or so before Luke anticipated his turkey would be ready to eat.

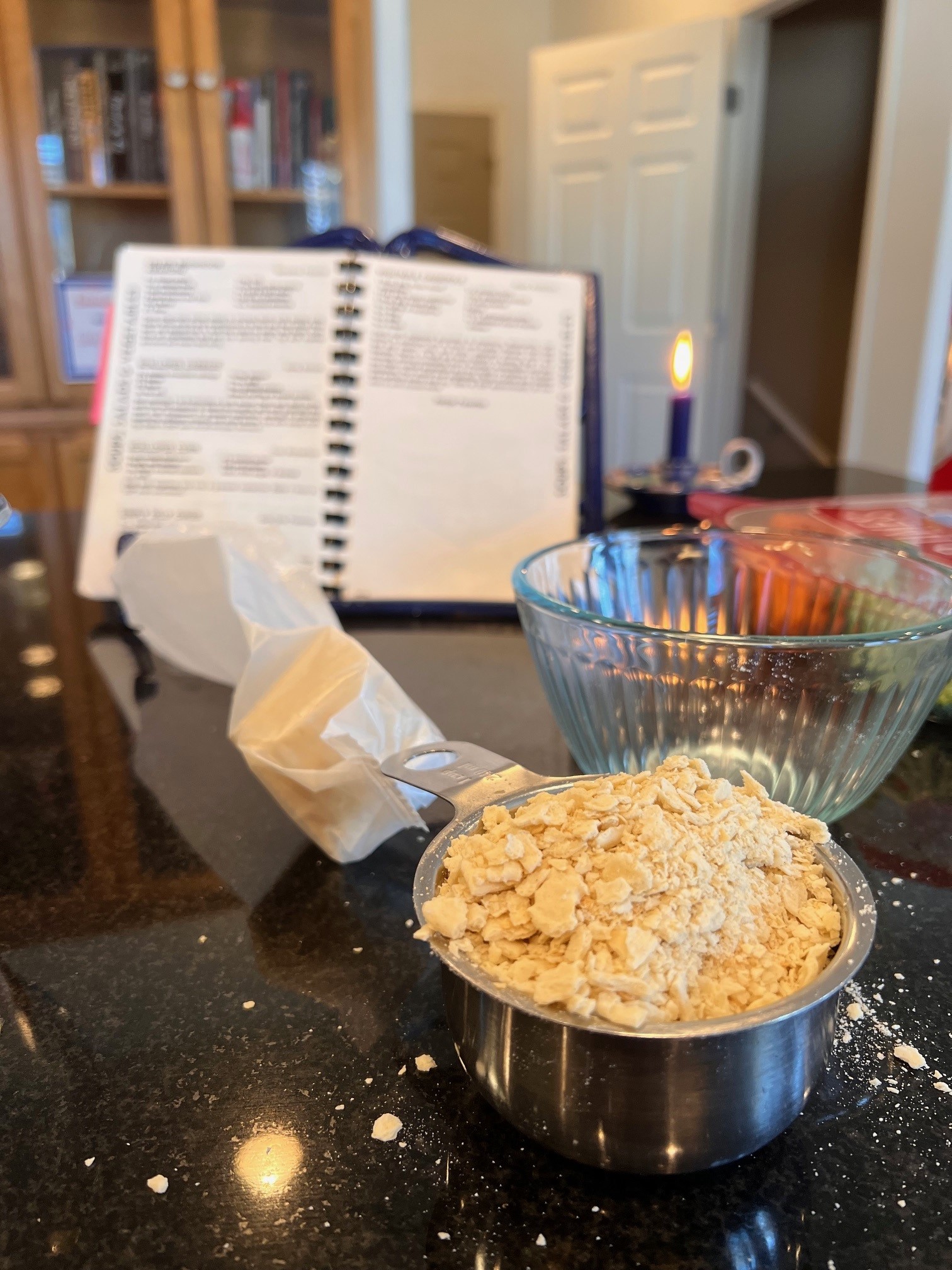

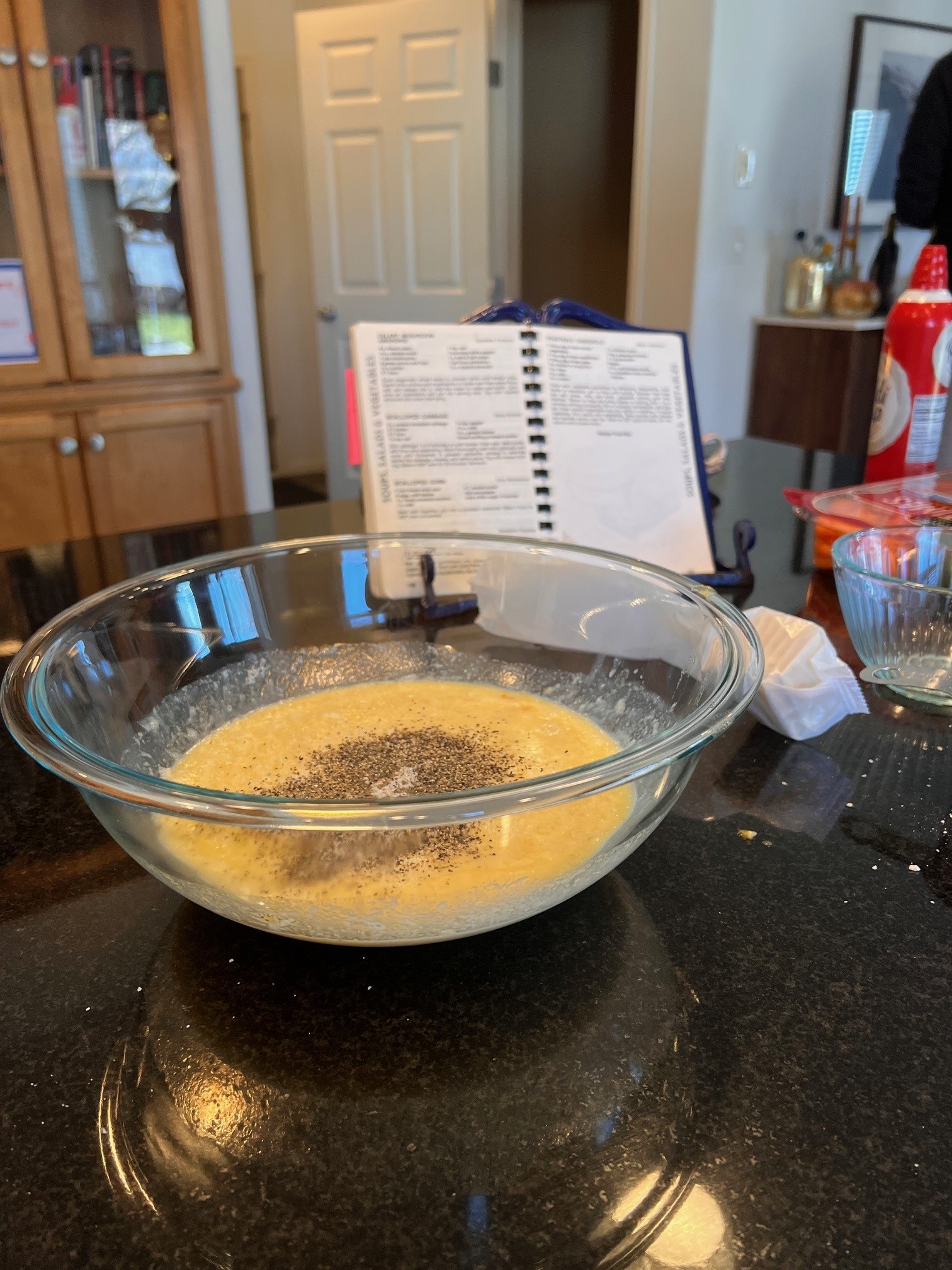

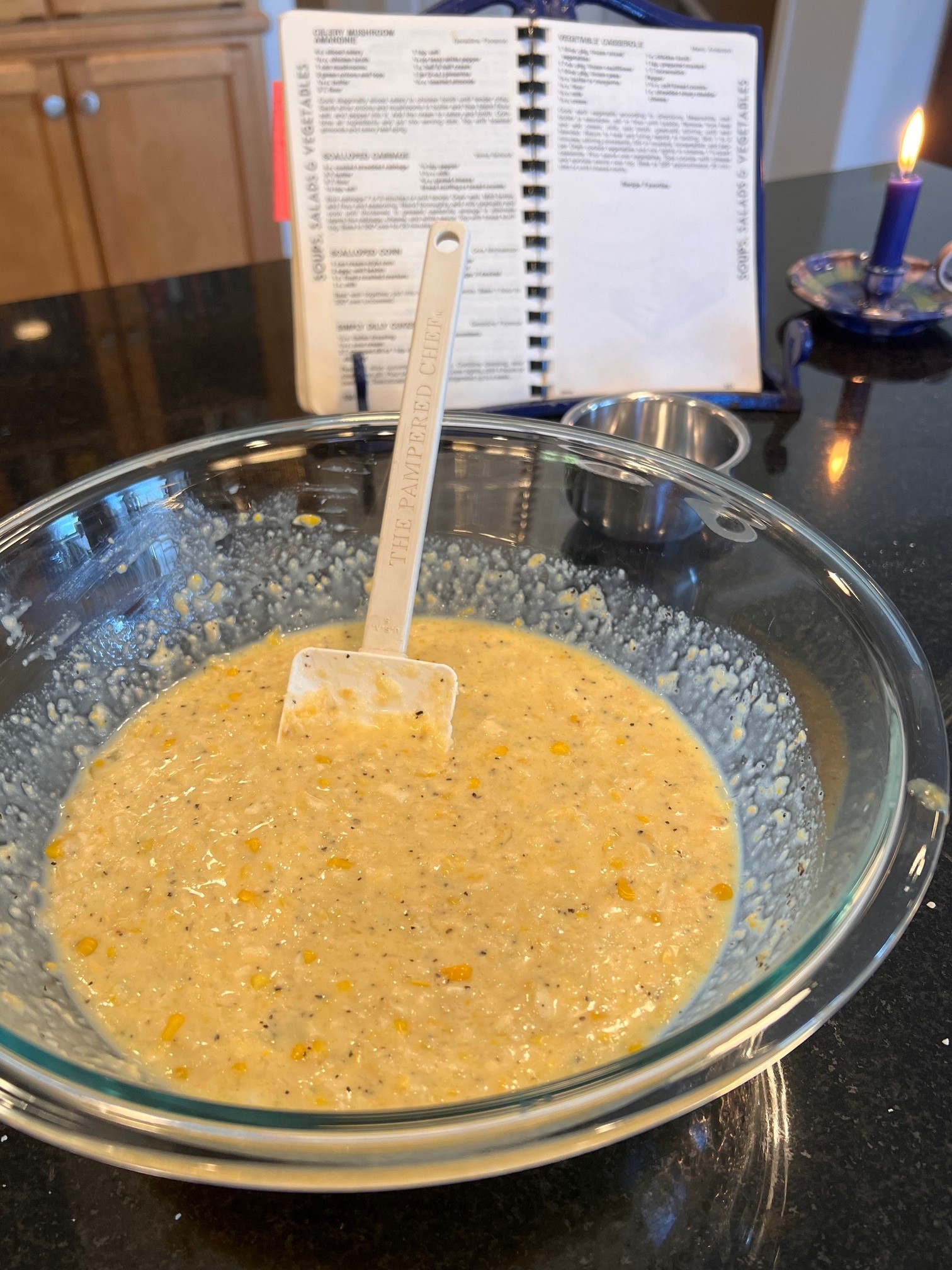

Though the corn and eggs were listed first, I read through the entire recipe to make a plan and began by melting the butter so that it would cool slightly and not scramble the eggs when mixed together. Meanwhile, I crushed the crackers with the handle of a wooden mixing spoon in the bottle of the mixing bowl until they were fine (read: until I got sick of crushing them), before I added the can of corn.

While Cora did not prescribe the variety of crackers to use, my prior experience involved saltines, and so I used those again. After pouring the cup of whole milk into the mixture, I beat the two eggs in the Pyrex measuring cup and mixed them into the large mixture prior to adding the cooled melted butter.

The amount of salt, pepper, and optional sugar was left to the cook’s discretion, and so I added a half a teaspoon of each.

I sprayed my largest Corningware oval casserole dish with cooking spray, poured the mixture in, and popped it into the oven at 350 degrees for the next hour.

I sprayed my largest Corningware oval casserole dish with cooking spray, poured the mixture in, and popped it into the oven at 350 degrees for the next hour.

In fact, it ended up begin a bit over an hour, as I got busy with talking with our families, pouring drinks, putting out snacks, and tasting turkey samples. Okay, really, I mainly was tasting turkey samples because turkey smoked on the Traeger is a thing of beauty.

Reflections

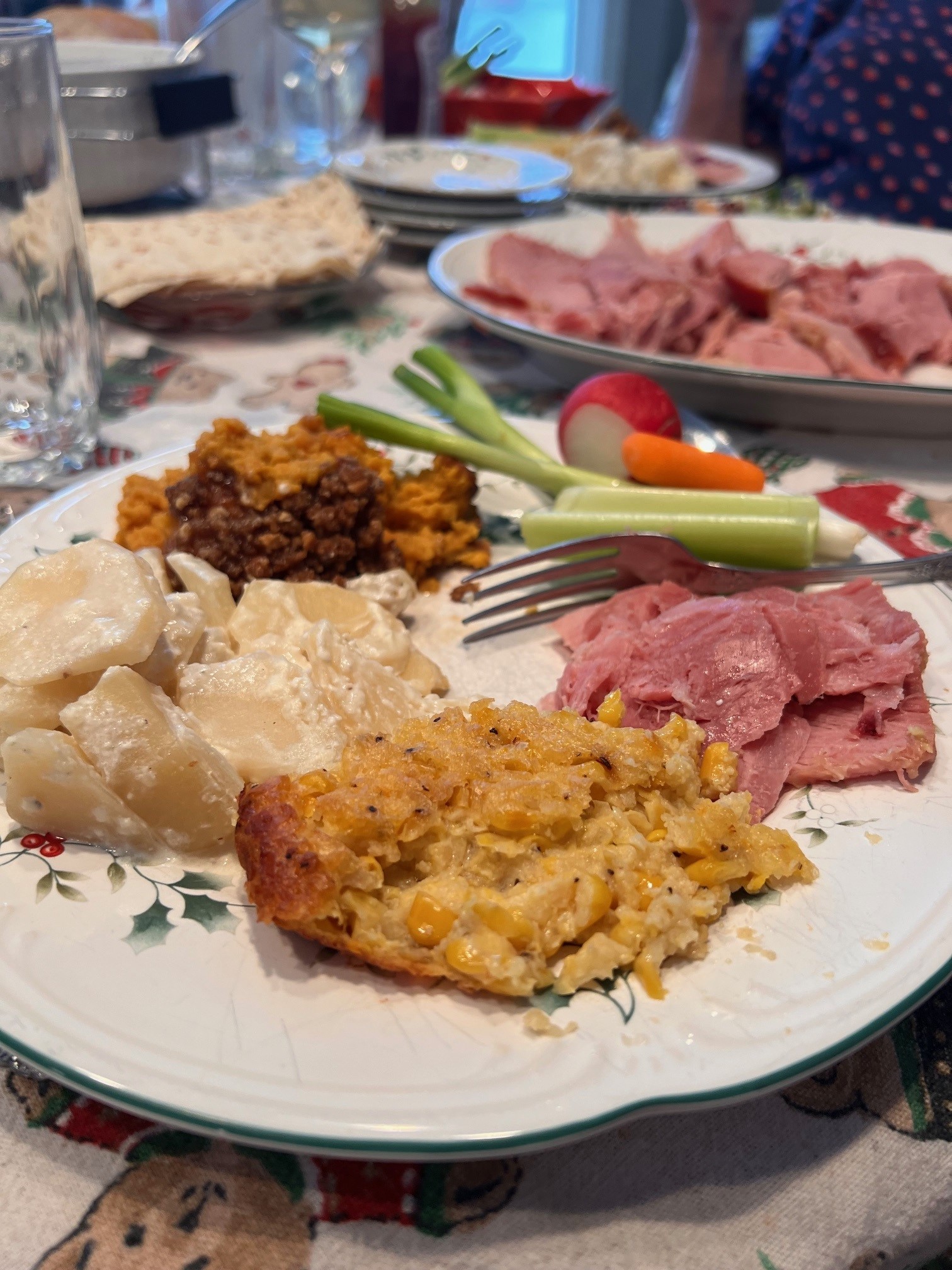

And so my casserole came out about 10 minutes late. But no matter. It was still amazing—golden brown, thick, yet soft, with a consistency similar to cubed bread in a dressing. Other corn casseroles I’ve made become gooey, particularly the ones with creamy ingredients like sour cream, cheese, and cornbread mix, but this recipe offered a softer center with a lovely crust on the top and bottom. The eggs, butter, milk, and cream-portion of the “cream-style corn” appear to melt into the crackers, creating a binding for the kernels of corn, which become more visually prominent yellow flecks.

So I made Cora’s scalloped corn a second time on Christmas Day to take to my parents’ house as a side for the ham my mom was serving. Once again, it was easy to throw together very quickly, could be ignored in the oven for an hour, and kept its warmth as it traveled ten minutes across town in an insulated carrier casserole. While my daughter declared she did not like a dish of this sort, it disappeared from everyone else’s plate quickly at both holiday meals. It was excellent, and I will make it again.

Scalloped

But there’s something about the word “scalloped” that remains unappealing to me. It’s a verbal, of course, a past participle, to be precise, a form derived from a verb but functioning adjectivally to modify the noun “corn,” describing what kind of corn it is. A verbal is a part of speech in which a verb is transformed into another part of speech; grammar gurus Blanche Ellsworth and John Higgins cheekily ask students “when is a verb not a verb? When it is a verbal.” Students find that joke extremely helpful in my upper-level grammar class, of course.

Since a past participle functions as an adjective, but is an adjective derived from a verb, it’s an adjective describing what has happened to the corn: it has been “scalloped.” This is similar to “whipped cream,” which has been…you guessed it…whipped. That’s why it’s not “whip cream,” a mistake I’ve seen in the wilderness occasionally, one which always reads to me like a command.

So what does it mean “to scallop”? The Oxford English Dictionary identifies the mid-1700s as the earliest instance of “scallop” used as both a verb and a verbal referring to cookery. “To scallop” means “To shape or cut (out) in the form of a scallop-shell; to ornament or trim with scallops” (Scallop, v. 1.a), which points to the prior existence of the noun “scallop,” which entered Middle English in the 1400s as a loan word from French, with the variation “escalope,” meaning “shell”; the French term is based on a Germanic word (what a fun etymology across language families! Germanic to Romance/Italic and back to Germanic). The OED provides three categories of related definitions for the noun “scallop”: a shellfish, the shell of the shellfish, and through the linguistic processes of semantic change called broadening or extension and figurative use, “scallop” also refers to objects resembling the shape of a scallop-shell, like scalloped edging of fabric.

Both past and present participle verbal forms of scallop appear in the second definition of “scallop” as a verb, which the OED indicates is related specifically to cookery and means “to bake (oysters, etc.) in a scallop-shell or similar-shaped pan or plate with breadcrumbs, cream, butter, and condiments (“Scallop,” v. 2). The earliest usage is from 1737, a reference to “Scollopt oysters” in James Colville’s Ochtertyre House booke of accomps, a multi-volume text published by the Scottish History Society discussing Scottish history and culture from the twelfth to the twentieth century (https://digital.nls.uk/scottish-history-society-publications/browse/archive/125651993#?c=0&m=0&s=0&cv=0&xywh=-1181%2C-1409%2C3926%2C4032).

Thus, “scalloped” as a cookery method may have originated from the use of the scallop-shell as a baking device. But its technique and ingredients appear to have become the defining feature of dishes given this label. Indeed, The Dictionary of Food: International Food and Cooking Terms from A to Z defines “to scallop” as “To cover with sauce and breadcrumbs and bake in a casserole,” and it also defines “scalloped” as “cooked in a scallop shell” (https://search.credoreference.com/articles/Qm9va0FydGljbGU6MTE5NTgyOA==). However, what is perhaps the most famous scalloped dish—scalloped potatoes—employs only some of these elements—cream or milk as a sauce and occasionally butter, but not the breadcrumbs, bread cubes, crackers, or flour or the cheese that is sometimes added. A potato-based dish incorporating those elements would be more properly described as potatoes au gratin (see https://www.thekitchn.com/scalloped-potatoes-au-gratin-difference-261486).

Figurative use may play a role in the label “scalloped potatoes,” as well, or at least in the folk etymology online speculators engage in as they try to identify the origin of the dish’s name. Many people note the metaphorical similarity between the round sliced potatoes layered in the dish and the round scallop shell or with scalloped designs. Other folk etymology enthusiasts point to an origin story based on the nature of the sliced potatoes and the word “collop,” a noun whose etymology the OED cannot trace with certainty and instead indicates is “of unknown origin…derivation obscure” (https://www.oed.com/dictionary/collop_n1?tab=etymology#8907066). While most definitions for “collop” are obsolete, they refer to slices of foods, typically meat and eggs, and figuratively, can be generalized to a slice or small bit of anything. Given the historical thoroughness of the linguists who created and maintain the OED, I’m less persuaded by the suggestions of various websites that “collop” is a verb meaning “to slice thinly” (see, among others, https://themodernproper.com/scalloped-potatoes).

But these certainly are not the retained meanings of the “scalloped” in other scalloped dishes. It seems most everything can be scalloped, regardless of shape. Perusing my cookbook collection, I discovered a wide variety of main ingredients cooked using this method; in The Joy of Sharing, Verna Shock instructs readers how to scallop cabbage and walleye fillets, and Leona Haga shares a recipe for scalloped salmon. The Church Supper Cookbook edited by David Joachim offers Spanish onions as the main ingredient to scallop. Perhaps most stunningly, Jaylen Newman recommends scalloping pineapple in the Velva School and Community Centennial Cookbook published in 2004 in honor of Velva’s centennial celebrations in 2005. Newman notes, “this is a very sweet and unique side dish” (39). Indeed.

Pointing to the continued use of “escalloped” as a variant spelling pointing to the Middle French’s origin point for the term’s transition into English, recipes for “Escalloped Corn” appear in the 1993 Velva School and Community Cookbook, submitted by Peggy Schmaltz, and in the 75th Anniversary Cook Book, 1905-1980 published by the A.L.C.W of the Montpelier Lutheran Church in Montpelier, North Dakota, shared by Ruth and Diana Dally, who mix things up with the addition frozen broccoli.

Scalloping is certainly very popular, and it’s no wonder why—a mixture of butter, cream or milk, egg, bread or cracker crumbs nestles the main ingredient in what is typically a creamy, warm bed. When we think of comfort food, most people think of soft texture and rich flavor—ooey-gooey, buttery goodness that warms us from the inside on a cool day. It’s also practical; as in other mixtures, the main ingredient can be stretched further.

Contributor: Cora Michaelson

Cora Michaelson is a bit of a mystery to me. The scant records I can find indicate that a Cora M. Michaelson was born on February 2, 1901, and passed on December 7th, 1996, at the age of 95, in Ward County. If this were the cookbook’s Cora Michaelson, it would make sense, as Ward is the neighboring county to McHenry and where Minot is located; many Velva-area people move to Minot when they retire or transition to a care facility. The McHenry County history book does not have a record for Cora herself, but a Cora Michaelson is mentioned in the entry for William Michaelson, her brother; the other Michaelson family histories in the book do not list anyone by that name. The entry focused on William, born in 1890, refers to two “remaining sisters,” including “Cora, who makes her home with him.” Cora and William’s parents were Andrew and Mattie (Reishus) Michaelson, who lived in Cottonwood and later, Porter, Minnesota. In 1916, William journeyed to Velva hoping to purchase a farm:

He found a farm that he liked located three miles north of Voltaire, so he made arrangements to purchase it from Thomas Oman. With the approval of his mother and the other family members, the sale was completed and the family moved from Minnesota to Lebanon Township in the fall of 1916.

Including these details regarding the shared decision to relocate of the family is fascinating to me—this was not a “young man ventures West to make his fortune” story, but rather a story of a 26-year old man finding a new place for his mother and siblings to live after his father passed in 1913, in addition to him securing a career and livelihood. William farmed until 1964 when he retired to Velva; another William—William Krumwiede—bought the Michaelson farm.

William passed on August 20, 1984, which must have been after the family history was submitted to the McHenry County history book, as it indicates that he and Cora lived together in Velva. I recognize this structure—of siblings staying together as a unit if they do not marry or move for work—as several of my great-aunts and great-uncles lived in the family home on the family farm for their entire lives. I hear of that less and less, and it’s hard to imagine it happening as often in contemporary society. But perhaps as social traditions continue to change, like children moving back in with their parents after college, we might see similar households return.

Cora’s other contributions include “Cucumber Relish” and “Banana Cream Pie (Graham Cracker Crust).”

This post is part of an ongoing series in which I make and reflect on recipes and the people who contributed them to the 1985 Oak Valley Lutheran Church compiled cookbook, The Joy of Sharing.