A day to wait in la ciudad de Los Ángeles.

Last night, after the train arrived, Paul and Edith and I said good-bye to Vergie. She has planned an extra day into her schedule here, a day to tour the movie sites and beaches and stores, so she’ll be one day behind us on the rails now. We said good-bye to Dan and Jimmy and Josh. Strangers two days ago, I thought. I will likely never see them again. But we part as friends.

Paul and Edith and I looked at each other, grinning. See you tomorrow!

I watched them all walk away, then stood in the middle of Union Station wondering what to do.

In a courtyard, elegantly dressed men and women danced to live jazz under strings of light. A wedding reception. White tablecloths, attentive waiters, a warm and clear night.

I could crash this party, I thought. Or I could stash my bag and find some jazz club. Or a moonlit Venice Beach. Or just wander famous streets and peer in windows. If you don’t know any better, Los Angeles at night is filled with promise.

Or I could call Uber and go to my hotel.

Months ago, while planning this trip, an L.A friend recommended the Hotel Normandie, and I am glad she did. The staff was friendly. The room was spacious. Even if I wanted to roll out of king size bed, it would take me several turns to get there, which, after the bed in the sleeper car, was a bit unnerving. The shower did not throw me against the walls. I unpacked, did some laundry, and repacked. I rested.

However, every time I looked out the window, which was across the room and not against my shoulder, the view was the same.

In the morning, my plan had been to linger. I thought I would break the cadence of the last few days. A slow breakfast. I was going to reacquaint myself with the feeling of being stationary. The train does not depart until 10:00 p.m.

But once I woke up, I had to get going. I had to get to the station. I could not make the train leave any earlier, but my head and heart were in that world and the rest of me needed to catch up.

There is an ancient typewriter in the lobby of the Hotel Normandie, which guests are invited to use. Old-school mechanical magic. I checked out, typed a note of praise and thanks, and headed to the rails.

So, once again, I am standing in the middle of Union Station, wondering what to do.

I walk to a waiting area with deep leather seats, a perfect place to settle and watch travelers pass, but there is a guard who checks your tickets. He will not let me in. You cannot sit there until two hours before your train, he says.

Bag on my shoulder, I go exploring.

There is a public piano and players who are very good. There are shops. And, of course, there is a movie set. This is Los Angeles. A section of the station is closed off, velvet ropes strung to keep visitors out. It’s classic art deco—think maybe Bonnie & Clyde, maybe retro-sci-fi-futuristic. The floor is more polished than in the regular station. The windows are taller. The wooden drawers behind the ticket counters look smooth. My notes tell me the Los Angeles police station scenes of Blade Runner were filmed in this room. Portions of The Dark Knight Rises and The Hustler were filmed here, too. The list is long.

I have a sudden wish. I want to take a picture from inside this room. I want to frame the windows and the counters and the floor. I realize this could all be a façade. It could crumple or topple in an instant.

So, I wait until I see someone who works there and ask if I can dash in, just for a moment. Run in. Run out.

She says no. I tell her I am working on a book and show her a magic letter I carry from Amtrak that gives me permission to interview people and visit rooms. She says, “Wait here,” and walks away.

When she comes back, she’s with some guy in a pork pie hat who has a New Jersey accent. He looks at me and my letter.

“No,” he says. “No way. No way.”

I think about making a run for it. I think about leaping over the ropes, dashing in to get a shot, dashing back out. I imagine myself doing one of those slow motion, long-distance, one knee on the ground slides, my camera up to my eye, suddenly capable of 1000 frames per second. But I can see another lady peeking around a corner, keeping an eye on me.

Even if I don’t get a decent picture, I think, the chase would be fun.

I pull a chair up to the ropes and sit down. Some other official walks up and asks me what I am doing. I point at the large room, the big windows, and explain I am going to wait for the shafts of light to change, to get a better picture.

He doesn’t trust me at all and I smile at him.

Every story needs a chase scene, I tell him.

I am enjoying this way too much.

“Vergie!”

“Hello!” she says, smiling big. We stand in the middle of the station, greeting each other loudly, like good friends who have not seen each other for years. “I got to my hotel last night and went through my papers and I had the date wrong,” she says. “I’m touring today, but I’m on the train tonight!”

“Wonderful!”

At 11:00 a.m. I am on a mission. My notes tell me there is a restaurant nearby, Philippe, which claims to have invented the French Dip sandwich. It’s only a few blocks away. I love a French Dip sandwich and I have in my head this image of a small table for one, a glass of wine, that wonderful moment when something familiar gets remade anew.

I cross the street and turn right, wander down to the corner of Ord Street. Then my heart falls. There is a line out the door. Hour and a half, I’m told, from the back of the line to the counter.

“Counter?”

“Yeah, there’s a counter where you order. Then long high-top tables you share.”

The day is already very hot. I turn around and wander back toward the station.

I walk up Olvera Street, the birthplace of Los Angeles, an open-air Mexican market with street vendors, painted stalls, noise, the press of a great many people, and music. Every café table is filled with loud and laughing groups. No place for just one, I think.

At the far end of the street, nearly back at the station, at El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument, there is dancing. There is dancing by an indigenous group and there is simply dancing, people in the park enjoying the music.

There is a certain joy that comes from watching happy people, I think. For some time I sit on a small wall and smile.

I have lunch at Café Crepe, an outdoor patio, round tables and birdsong, the part of the station where the wedding reception was held. A beef and cheese filled crepe and a glass of chardonnay. Very nice. Quiet.

When I am done, I walk back into the station.

“Scott!”

“Paul! Edith!”

“We just had lunch at Philippe,” Paul says, beaming.

“It was great,” Edith says.

“We’re going back there for dinner,” Paul says.

They do not understand my frown.

The sounds of a jazz concert come from another courtyard, maybe a hundred people sitting on folding chairs listening to classics. There is cold ice-cream from an inside shop. Eventually I find my way upstairs, to the sleeper car waiting room lounge, where I meet Doug Busler, a locomotive engineer for Amtrak.

The room is full of people—impatient adults and impatient kids—but Doug is telling train stories and the space around him is quiet. I have no idea why he’s here, but here he is, telling stories like a wise grandpa.

“Currently 28 years of service,” he says. “Well, for thirteen years I worked for the Burlington Northern railroad as a brakeman, switchman, conductor. And then had an opportunity to go to work for Amtrak at the end of 1991. I began my training in San Diego in 1992. That training led me to an assistant conductor position in Pendleton, Oregon, on one of the trains that doesn’t exist anymore. Number 25 and number 26, the Pioneer. That one had a route from Seattle through Portland, eastern Oregon, into Boise, and then southern Wyoming, to just outside of Cheyenne. And then down into Denver. Doubled together with two other trains that had doubled together in Salt Lake City. A trilogy of trains leaving the west coast that became one in Denver and then continued on into Chicago.”

These are trains that don’t run anymore, I think. Trains that join in the middle of the night and head east across the prairie toward Chicago. There should be music.

“We had some downsizing in the 90’s that finally did away with that train,” he says. “But with my limited seniority I went to Seattle. Split a first year working between Seattle and Portland as an assistant conductor and then conductor and ended up staying in Seattle throughout the 2000’s. Working trains 7 and 8, the Empire Builder. I was involved with re-inauguration of service between Seattle and Vancouver, British Columbia in the early 90s. In 2000 I came down to San Diego and was there for a year. Los Angeles for two years. Went back to Denver for family reasons for a couple of years. Then back to San Diego. Currently working out of Los Angeles crew base.”

“What made you switch from freight to passenger?” I ask.

“I had given twelve plus years to the freight industry,” he continues, “most of my 20s, and that’s kind of an unforgiving lifestyle. I was living in a fairly, you know, by city kid standards, a fairly remote part of the United States. In Wyoming, and western Nebraska, and eastern Colorado. Working in the coal division for Burlington Northern. I was looking at doing some other things because they were going to start reducing the train crew size. I was looking for an opportunity to maybe leave the industry. But some friends in Denver encouraged me to look at the Amtrak possibility and to look at Denver because they were a little short-handed. I did and one thing led to another. And now I’m sitting here talking to you.”

Doug has an easy smile.

“Is it much different, between freight and passenger?” I ask.

“There is a significant difference between the operating characteristics of a passenger train as opposed to a freight train. The operating rules are basically written for freight trains and modified for passenger trains. The rules themselves are fundamentally the same on any railroad that you run. In some cases, though, the speeds are dramatically different. In some cases, only subtly different. You don’t want the couple in the lounge car to have their coffee slide across the table and then some acrobatic maneuver to catch it.”

“What’s it like up front?” I ask. “You have the tragedy of hitting someone, but you also get to see some of the most beautiful scenery in the country.”

“Well,” he says, “somebody asked me just the other day if I miss seeing the vast amount of wildlife that I had seen earlier in my career? Working in Wyoming on the freight railroad, working up in the Pacific Northwest, you saw it all. I had slumbering brown bears in the sunshine of the Pacific Northwest snoozin’ on the tracks. Then here I come along and they make a mad dash for cover. But yeah, I mean, everything.”

“Tell me a story?”

Doug leans forward and I watch the posture of a dozen people change as they lean in to listen.

“There are some people who don’t believe my story about how I may be the only guy who ever hit a salmon.”

“A salmon.”

“Yes.”

“The fish.”

“Yes.

I wait for him to continue.

“Leaving Vancouver, Washington, on an early morning, what became known as the Talgo project, we had a very light-weight train and we had what are now the older locomotives, the F40, built by EMD. Three thousand horsepower passenger locomotive, but a very light-weight train. I was accelerating out of town and it was just kind of a natural acceleration down by the Columbia slough. As I was approaching the maximum authorized speed on the land side of a two main track territory, out of the corner of my eye I saw a bald eagle coming up out of the slough with a pretty good-sized salmon. And all of a sudden the bald eagle realizes he’s not going to make it. He’s flying inland and he’s not going to make it with his payload. So, he drops the payload and the salmon hits the windshield of the locomotive right in front of me.”

The people listening around us, adults as well as children, are all wide-eyed.

“Everything happens on the rails that you can imagine happens,” he says. “That’s one I don’t think too many people have experienced.”

“Is there a regret from sitting up front?” I ask.

“I’m not a person who has much of that.”

“What about tragedy?” I ask. “What about people who shouldn’t have been there?”

“Too many,” he says. “One is too many.”

“How did you handle the first one?” I ask.

“Well, everybody does it a bit differently,” he says. “My first one was not easy. Your perspective changes because you’re seeing the scenario unfold in front of you. You see it happen. Unfortunately, that will always be with you.”

“Compliance,” he says, “is paramount for me to sleep at night, knowing that I did everything that I was supposed to be doing. And I don’t’ have much control over the outcome when somebody decides to do not what they are supposed to do.”

“What route are you doing tonight?” I ask.

“My same route,” he says. “The one I work regularly on Monday Wednesday and Friday nights, which is up to Goleta, California, which is ten miles north of Santa Barbara.”

He pauses and smiles at me.

“You caught me on my day off. They were a little short, so I came in.”

I do go back and have an extraordinary French Dip sandwich. Then I drink too much coffee in the departure lounge. Waiting.

Finally, on time, the Sunset Limited departs Los Angeles. I love the sound of an engine coming up to speed. Paul and Edith are in the room next to mine. Not across, but next to. I have no idea where Vergie is and hope she’s made it back.

I settle into the room and then into sleep, the rocking of the train a comfort after stable ground.

~~~

I wake up to quiet in the middle of the night. There is no whistle at crossings. There is no sound of wheels clacking over the rails. I raise my head and look out the window. A single palm tree stands just outside my window in a field of freshly fallen snow.

“Pretty,” I think, resting my head on the pillow.

Then it occurs to me. Snow? I look again. The sand is pristine white.

“Even prettier,” I think.

I have no idea where we are. I have no idea why we have stopped. Oddly, sleeping in a train that is not moving feels vaguely like trespassing.

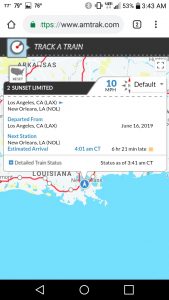

8:20 in the morning and we are already three hours behind schedule. We have passed through Pomona and Ontario and Palm Springs and Yuma, but we are still half an hour, or more, on the west side of Maricopa, Arizona. We should have been here at 5:00 a.m.

Beautiful hills. Desert. Clear sunny sky.

Last night at 3:00 a.m., there was a voice in the stairwell that just kept saying Hello?Hello? Is anybody up here? Hello? It was a quiet, woman’s voice. She needed help but didn’t want to disturb anyone.

The attendant got up, and I heard the woman explain that she thought somebody downstairs may have had a stroke. The person was having difficulty getting up.

The attendant and a conductor checked on him and the man had not had a stroke. He was just slow getting up. But we waited at Yuma, I believe, for some time. I don’t know if we were waiting for this.

Breakfast is lovely. I sit with an English teacher who teaches at a residential school for children who are wards of the state. His college degree was in psychology but he wound up teaching English. We talk about the usual things. Why are you on the train? Where are you going? The joy and pain of being delayed. And politics.

Now we’re chugging through the desert. No big adventures or stories to tell yet. Beautiful scenery. I’m told it’s going to be 110 degrees in this neighborhood today.

We pass the Pima air museum and the Tucson airplane boneyard off the left-hand side of the train. Too far away to get a picture.

I settle into my room with my camera. We are behind schedule and losing time.

Perfect, I think.

Wonderful and fine.

Adventure arrives. Or at least the risk of being left behind.

Blame it on my notes. Blame it on knowing something in advance.

What I know is that in Benson, Arizona, right at the train stop platform, there is an ice cream shop. It’s supposed to be very good. The Old Ice Cream Shop promises 50 varieties of soft serve ice cream. The list is on their web site.

I want to make this happen.

“What do you think?” I ask the conductor. “If I get off the train and make a run for it, what are the chances I’ll make it back to the train?”

“Oh,” he says, “you’ll make it back to the train. It just might not be this train.”

The stop will be very brief, one where the train pauses only long enough to let people on and off. The platform is only one train-car long. Three minutes, I’m told, at the most.

This could work, I think. This is going to work.

I call the ice cream shop and talk to a young woman named Vanessa. I explain the hope and the problem. She says she could make it just a little in advance, if I knew what I wanted, and put it in the freezer. All I need is to tell her was what I want and when I would be there.

I know what I want. I have no idea when we will be there. The conductor tells me a freight train in front of us has stopped and we are waiting for it to get moving again.

“When we get there,” he says, “the platform is only one car long. So the train stops for one car, off and on loads, then pulls forward to the next car, off and on loads, etc., until it’s done.” The conductor tells me I should be able to make it, but I might have to get on the train a few cars behind my own.

“Of course,” he says, “if there’s no one to get on or off in the cars behind us, then it’s a very fast stop.”

“What kind of soft serve do you want?” I ask. “My treat.”

The conductor wants pistachio. Insurance, I think. He’s the one who tells the engineer when it’s clear to go. Our car attendant wants cheesecake. I want peach. I call Vanessa again.

“You got it,” she says.

We meet by the door just before pulling up to the platform. Lots of guesses about whether or not I will make it to the ice cream store and then back to the rail car in time. Paul comes down and I hand him my camera to take pictures. I don’t think about what will happen if I don’t make it.

As we arrive, the conductor calls out distances on a radio to the engineer, how far away we are from the platform.

“Fifty feet Amtrak.”

“Ten feet Amtrak.”

“Five feet Amtrak.”

He does this to make sure the car is lined up with the passengers waiting to get on the train. It’s also a bit like a countdown. Ready. Set.

When we stop, the door opens and I take off at a dead run. Or at least what is a dead run for me. In the store, Vanessa has the three ice cream bowls waiting for me on the counter. I put down the cash, grab them, smile, say thank you, and take off to get back. I can’t tell if she looks more amused or alarmed.

I make it back to my own car. Everyone is impressed. The ice cream is very good.

After Benson and after the soft serve, I finally have a conversation with Adrian Hunter, our car attendant, about last night.

“The stroke,” he says.

“Yeah.”

“The panel light in my room woke me up. Then the woman calling hello. She wasn’t calling ‘help’. She was calling ‘hello’. So, I got up and went to see what she needed. He said he was fine. He just takes a while to get up. She kept saying ‘the person I’m traveling with’. Not husband or boyfriend or friend or even a name. ‘The person I’m traveling with’. It made me wonder if they were fare evaders.”

“Fare evaders?” I ask.

“Stowaways.”

“Amtrak has stowaways?”

“All the time,” he says.

I wait.

“Go on,” I say.

“Oh yeah, very interesting. We had a couple on this train. I think it could have been nipped in the bud earlier, like in Los Angeles, but there was miscommunication between me and the conductor. I’m out on the platform, Los Angeles Union Station, and I’m boarding passengers. Everybody’s pretty much onboard. And these two people come over. They seem like a couple, I guess. Kinda mid-thirties. They’re kinda,, how do you explain it, kinda rough around the edges. They look like drug addicts. And they ask me where the coach is. So I say yeah, the coach is down at the other end of the train. They’re like okay, and just head off. And I think that’s the end of it. Then all of a sudden they come back. They say, oh we’re sleeper passengers. I say oh, really? I thought you were coach. They stay quiet. They don’t say anything to that. I say ok, well, do you have a ticket?”

Adrian pauses.

“And I think they tried to change the subject. And they say oh, yeah, but we should be on there. You have the Johnson family on there? I look it up and I don’t see any Johnsons. That’s a good generic name, though. It’s quite possible it could have been there. And I say you know, it’s easier that I could just look for a room number because it’s hard to see with all these names on here. And they say oh, room 7. Alright Room 7? I’m like okay, room 7. Jack Little and Judy Little? That you? Or I say Little? Little family? And they’re like yeah, we’re Little. We’re Little. Alright, I say, and you’re Jack and you’re Judy? I stare at them for a bit. I stare at the paper. I don’t believe these people for one second. But I’m going to let the conductor handle it. I’m like, alright. Come upstairs. Go to the room.”

“And then guy gives me a big big smile,” he continues, “like yeah. He’s happy that he got through. Probably didn’t believe that it would work but it worked, I guess. But I told the conductor right away. I was like, check room 7. I don’t think they are who they say they are. Just scan their tickets, do something. Figure out where they’re supposed to be. Little did I know that the “Littles” probably never went to room 7. They probably found some other place to hide or something. But the conductor went to Room 7 and talked to the real people. The real Littles. I told him what my couple looked like, but he apparently talked to some elderly couple. This nice little couple. He said to me, I scanned them—they’re good. I didn’t know that he scanned some other people, so I’m like okay, they’re good. Alright. And I felt like that was the end of it. They had the curtains closed and it was nighttime. We were all going to bed. Alright. Worry about it in the morning, I suppose.”

“In the morning, the next day,” he says, “I have an empty room, room A, and I put some laundry or some linen in there that I didn’t have room for and I’m going to go retrieve it. I open the curtain and there they are, those two people that were downstairs telling me that they were the Little family. And they got some sheets, all cuddled up together, sleeping. Having a good time. And somehow, me, I thought they’re still the Little family. They thought they could go to a different room. So I said, “you guys should be in another room. I need this room, this empty room. Please get out please?” They go okay, all groggy.”

“Did they trash the room,” I ask. “Use the bathroom and everything?”

“No, at least they were nice enough not to do that. They must have pulled out a sheet I had in my linen bag. They used that and they used the pillows, but that’s when I just got curious again. Why are they sleeping in this room? Why didn’t they just stay in their room? So I go to check on that room. I knock on the door. Room 7. No one’s there. I ask the lady across from that room, have you seen the people that have been here? And she’s like yeah, it’s an elderly couple. And I was like, really? Alright, I call the conductor again. I go to the conductor downstairs, where he’s hanging out, and I was like, I told you, I told you they were wrong. Those people that I said were the Little family, that claimed they were the Little family, they’re still here and they’re hiding. They’re in room A and you gotta go check on them. He’s like, okay, let’s go get ‘em. We got fare evaders. We got ‘em.”

“Does that happen a lot”

“Yeah. Some people who are chronic fare evaders have their pictures up on the walls at Amtrak stations, in the offices and such.”

I laugh. “So, what happened?”

“So, I came with him,” he continues. “I escorted him back to room A. Actually, we had two conductors. Assistant conductor and conductor. I open the curtain and they talk to them. They say hey, you guys supposed to be here? Can we have a ticket please? And I wasn’t looking at them. I was just looking outside the door at the other conductor, while the first conductor was talking towards them. And they didn’t yell anything out. They just played dumb. Grabbing at pockets. Patting their pants. Where’s the ticket? Oh, do you have the ticket? No, you have the ticket. So the conductors were like yeah, you’re not the Littles. It’s obvious now. So you can either buy a ticket for this room, or you leave at the next stop.”

“Why not put them off into the custody of a sheriff,” I ask.

“Not to be delayed any more,” he says. “Waiting for authorities can take a while. The time it would take to wait for the police and explain what was going on. Sometimes they don’t even want to come.”

We watch a dust devil dance along the desert beside us.

“They were pretty calm about it,” he says. “I guess they were just tired. They were all groggy. Didn’t put up a fight or nothing. And off they went.”

I am talking with Sean Smith, a conductor based out of El Paso.

“Rule 1.1.1.1.1 is that whatever happens, it’s the conductor’s fault. The conductor is ultimately responsible for everything that happens on the train.”

Outside, desert stretches in every direction, and in every distance there are mountains.

“In spite of the late train today,” he says. “Today has been a typically uneventful day. It’s been an incredibly fantastic day. But it’s been a typically uneventful day.”

“On a typical day,” I say, “you scan tickets. You radio where to stop…”

“It starts with the crew briefing,” he says. “Everything starts with the crew briefing. Last night we got on the train at 10. We hold the operational briefing, review all the restrictions from the host railroads we travel on. For us so far it’s Metrolink, SCRRA (Southern California Regional Rail Authority), and Union Pacific. Out here it’s just Union Pacific. So we review our Union Pacific orders, and we all go over it together.”

“Standing orders,” I ask. “Or do they change?”

“They are different for every tour of duty” he says. “Some of the restrictions have been there for years. But things change.”

“Such as?” I ask.

“Well, you basically have three types. Form A’s, which are generally speed restrictions. Form B’s—they pound it into you in assistant conductor training that B stands for blood, because that’s where men are working. And if you’re not paying attention to your job you could kill someone. And then Form C for just general stuff, like at this milepost blow extra bells and whistles because they’re having a parade nearby. Something like that. It could be just that simple. Or it could be that a wayside detector is out of service.”

“Is it difficult, mechanically, just to keep the train together,” I ask?

“Are you a car guy?” he asks.

“A bit,” I say.

“Like antique cars? Or, not necessarily antique, but classic cars? Pre-computer cars?

“Yes.”

“Computers control just about everything these days,” he says. “But we’re talking about equipment that was built, originally, before computers ran vehicles. Now they’ve adapted, they’ve been upgraded, they have all new systems in place. The most popular one, the most well-known one these days is PTC, positive train control. But it’s still equipment that was built back then. There are millions of miles on this equipment. They were built really really well. I mean, stainless steel bodies. Diesel electric motors. They run for millions of miles. They are a marvel. A lot easier to take care of than steam locomotives. But they still need attention. Every trip there’s something different. Sometimes the bathrooms go out on a car. This has been a very uneventful trip. The only thing I’ve had to write up is this dining car we’re in right now, because that half of the dining car is warmer than this half. I’m no mechanic. But in my eleven years and one week of experience, I’ve learned that if half the car is hot and the other half is operating properly, then it’s probably a condenser that’s frozen up on one end of the train. And there’s really nothing we can do about it except try and bypass the air-conditioning system in between meal periods, which will give it an opportunity to defrost.”

“So you know the mechanics of this train, stem to stern, I say.

“No no no no no,” he says. “Operational rules for conductors pale in comparison to the mechanical aspect that the engineers know. They are much better trained in the mechanical end. We have the delicate balancing act of being in charge of the engineers, but also being in charge of the onboard service crew and being ultimately responsible to the passengers as the face of customer service.”

“Tell me a story, good or bad, that’s unusual in your experience,” I say. “You say this has been uneventful so far. But we’ve had stowaways, we’ve had a freight train in front of us hit someone, we’ve had a possible stroke and we’ve had siding-length issues I’ve been told. And now the air-conditioner.”

“One of the best stories I can tell you,” he says, “happened today. I was walking through the dining car and I said to one of the passengers, ‘Has anyone ever told you that you look remarkably like Robert Earl Keen?’ He turned around and said, ‘I am Robert Earl Keen.’ I said, ‘you’ve got to be kidding me.’ He’s one of my favorite artists. He’s one of just four channels I have on my phone. He’s right up there with Frank Sinatra, Jimmy Buffet, Robert Earl Keen. He’s traveling with his daughter. Turns out they have a ranch in Marfa, Texas, where the other half of the crew goes. Out of El Paso we go west to Maricopa or east to Alpine. For folks getting off to go to Marfa, Alpine is the stop.”

All I can do is shake my head in wonder.

“Any weddings?” I ask. “Any babies born? That kind of stuff?”

“No weddings on the train. But we have had to take people off the train in El Paso because they were going into labor. And if you don’t get off in El Paso, you don’t want to try and push it all the way to Alpine. Or all the way to Deming. We’ve had people that did not want to get off in El Paso because they didn’t’ want their babies born in Texas. For whatever reason.”

“Everything is a challenge on the railroad,” Sean says. “Because no two days of work are the same. We may travel the same territory every day, but the trips are different because the passengers are different. And that makes every day special.

“I’ve been working out here in the desert since December of 2011. And, you know, the desert can be kind of boring. Then sometimes you get a drugged-up kid who attacks your 70-something year old conductor and you have to jump on top of this kid and hold him down for twenty minutes until the police arrive.”

“What is the relationship between a train and local law enforcement,” I ask. “You are in their jurisdiction for what? Ten minutes?”

“Sometimes,” he says. “Sometimes less. Sometimes more. And it varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. I’ve worked with conductors who have tried to contact police and they don’t respond. We’ll sit there for an hour waiting for them to show up. I’ve gone through jurisdictions where you make one phone call and you’ve got four cars arriving.”

“But you can’t just stop the train right now and boot me off and say see ya?”

“I can’t,” he says. But the lead conductor can.”

“Really?”

“Only if you cross her,” he laughs.

“If I went in the back and started pounding on someone?”

“Yeah, we would probably stop the train at the nearest crossing, and the police would come and take you off.”

“But you’re not going to leave before the police show up. It’s not just boot you off and go away, leave me alone in the desert.”

“No.”

“You told me earlier that you’ve had six human accidents in your career,” I say.

“Two of them happened in one accident.”

“There’s part of me,” I say, “that thinks I could handle that. There’s a part of me that knows it would be difficult.”

“I’m insulated,” he says. “I’m in the body of the train. I don’t see the moment of impact the way engineers do. It’s far more traumatic for them. My first incident was working on the Coast Starlight. I was the assistant conductor. The conductor went to find the bodies because the engineer said oh my goodness, I think we got someone. We stopped the train. I walked around the train, starting here at the front end, all the way down to the end, circling around the engine. And that’s when I saw the point of impact. Brain matter and stuff. That was my first experience. It was not nearly as bad, nowhere nearly as bad, as what the engineers experience.”

“How often do you take out cows, or something like that?” I ask.

“Cows? Not that often. You’re going to be on this train all the way to New Orleans. Up near Marfa and Alpine there’s a canyon you go through. And there are herds of wild aoudad that roam there.”

“Aoudad?”

“Looks like a goat with big ram’s horns.”

“I was on a crew,” he continues, “where we were back here in the body, and all of a sudden we hear what sounded like tons of ballast, you know, the rocks and the gravel bed popping up underneath the train. No, it was the shattering horns of about 25 of those things. The herd just went across in front of the train. Nothing the engineer could do.”

As we are talking, tones and bells and conversation come over his radio. Waypoints are acknowledged.

“Who all are you connected to on your radio?” I ask.

“Well in this crew there’s the conductor, the assistant conductor, the engineer and the fireman. Dispatch is listening. Anyone could be out there listening. Signal maintainers, maintenance crews. Today we are traveling from Maricopa back to El Paso, but there was a train that went from El Paso to Maricopa on Sunday and it did not get to Maricopa in time for the crew that worked that train to be rested to work back, so they are actually dead-heading back with us. I know at least one of those guys is listening.”

“Because?”

“Because he does.”

“Not because he should.”

“No, because he can. He wanders around the train looking for trouble. He spotted a guy who snuck beers by the gate in Tucson, past the conductor. I went and confiscated the beers from the passenger, and it turns out he had brought a bottle of gin along also. Just a little pint of gin. But I had to confiscate all that stuff because you’re allowed to have your own alcohol if you’re in a sleeper car, just not in the public area, back in coach.”

I ask about fare-evaders, the FBI style posters in the crew rooms in stations.

“There’s only been one fella I know of, he says. We call him the Russian. I call him A Number One because I like the movie Emperor of the North. He’s a fella that’s constantly hoboing around out here. He’ll be on freight trains. He’ll be on Amtrak trains. You’ll see posters that say he was last seen in Seattle. He was last seen in El Paso.”

“Is he that good?” I ask.

“You could be that guy,” he says.

“So, you’ve never actually seen him.”

“I’ve seen him. But the three times I’ve seen him, his appearance has changed every time.”

“You really don’t recognize me?” I ask, and we laugh.

“Does he do it just for grins?” I ask.

“I don’t know. Hoboing is a lost art in this country. Until the next great depression, which might be closer than anyone thinks.”

Passing through El Paso, passing by where we can see into Mexico, a lady in an ARMY t-shirt comes into the dining car with what I assume is her son.

The server has been greeting everyone as happily as can be. Everyone is Dear and Honey and Hon.

“Hi Hon!”

“What’cha need, Honey?”

“Dear, I love all the food here!”

The woman and son come in, sit down at the table across the aisle from me, and a moment later she points at a section of border wall with great pride. “Look at that! Isn’t that great?” And a moment after that she sees someone walking on the railroad tracks.

“Oh oh oh,” she exclaims. “An illegal immigrant!”

“How do you know?” I ask.

“He’s Mexican and he’s walking on the tracks.”

I point out that he is wearing a hard hat and an orange reflector safety vest, but she just looks out the window.

A moment later a helicopter flies by.

“Just watch,” she tells her son. “They’re going to get him.”

The server comes up to her table.

“What can I get for you?” she asks.

The missing Dear or Hon is huge.

The lady says she is going to take food to go, and the server politely tells her she will have to talk to her car attendant for that.

At the San Antonio fuel yard, where we get diesel and water, we discover somebody pressed an emergency stop earlier in the morning and they haven’t been able to get the mechanics all running again. So, after waiting there for about half an hour, we’re backing up to another fuel yard.

We are three and a half hours behind schedule.

When we get going again, in that space between meals, in the space between cities, everyone in the sleeper car has their sliding door open, their curtains pulled back. Everyone watches the scenery race.

Vergie walks by and says hello. Paul walks by. Edith walks by. Adrian and Sean walk by. Everyone nods or says hello or stops to talk.

Then, for whatever reason, the engineer dumps air, puts on the brakes, hard. Every sliding door in the car slams shut with the force and energy and sound and surprise of a door in a house that slams shut because of wind through an open window. Every heartbeat leaps.

“Well, that was a surprise,” Paul says when our doors are open again.

We all laugh, and then the engineer does it again.

A day goes by. I watch desert become suburbia become desert become city.

In Houston, on a 95-degree, sunny afternoon, a group of senior citizens, forty or more of them, wait in a small station house and then board the coach section of the train. Several of them struggle with walkers, canes, etc. All of them shuffle. First one from station door to train is a man with a walker.

In Beaumont Texas, which according to my notes is the town from the movie “Footloose,” where dancing is not allowed, the group of senior citizens gets off the train. I don’t know where they are going, but they all get on a Harris County Precinct Two bus. A police bus. A uniformed police officer helps them onto the steps. Criminals, I think! Desperados! Texas bandits!

“I’ve figured it out,” Paul says. “Adrian is the yin to Dan’s yang.”

My phone beeps a flood warning for Beaumont, Texas. The Neches River Salt Water Barrier.

Nothing is impossible.

We cross into Louisiana as the sun goes down, five hours behind schedule. The trees and wetlands get dark, but the clouds for a brief time are a brilliant orange. Music by George Winston comes from my phone. The train has picked up some speed after another delay. Now we are racing toward New Orleans. Lake Charles, Lafayette, New Iberia fly by. We are so late time has become irrelevant.

At 9:00 p.m. the train comes to a stop on a dark and remote siding. An announcement comes over the PA that the conductor has to get off to hand-align a switch. We are on this siding to allow a freight train to pass by. Looking at my watch, thinking about my hotel reservation in New Orleans, I am convinced I’ll be lucky to get there just in time to check out.

It’s way too dark for photographs, but I am struck hard by the beauty of a full moon rising over flatland and water, the sound of a train whistle in the distance, the orange moon as it rises over Louisiana.

Previous: Coast Starlight Next: The Crescent