I am impatient with Seattle.

When the Empire Builder arrives, we disembark. Linda talks with everyone from her car, our car, wishes us all a happy whatever comes next, and we agree we are going to miss her.

Paul and Edith head off, calling “See you tomorrow!”

No one seems to be in any hurry.

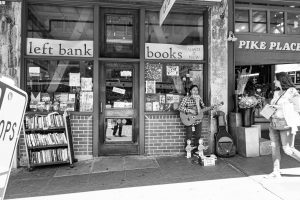

My aunt and cousin and her husband live in this city and I’ll be spending the night at their house. But I’m several hours ahead of the time we said we’d get in touch, so I check my bag at the station and go wandering. I have enough time to walk around, but not enough time to go deep, so I decide to be a tourist and head toward Pike Place Market, stop in shops along the way, listen to a little street music. In a few hours I’ll take a ferry the short distance across Elliott Bay and settle into good food and family talk, all the stories of remembered youth.

I like Seattle. Though, in truth, I already want to be back on the train.

The next morning, I arrive at King Street Station at 8:30 for a 9:45 departure. The lobby is nearly empty and filled with light. Bright chandeliers hang from an ornate ceiling. Long wooden benches rest on the terrazzo floor.

It feels—grand.

It feels—big.

The weather is cool, overcast. Fifty-nine degrees on the way to 70. The woman working the counter smiles as every one of us asks the same question in turn.

“Gate 3,” she says. “Gate 3.”

“Gate 3,” we reply, turning to find the doorway.

At 9:15 we are allowed to board. I find my way down the platform to my car, step up into the hallway and smile when I see the coffee is ready. I put my bag on one seat and slide into the other to reach for my camera. It will be a while for everyone to get onboard, but I am ready for the stirring of the engine and the rock of the cabin. I’m ready for the landscape at speed.

This is a train of recent legend. Last winter, heading south through the mountains, the train ran into a snowstorm and then a downed tree near Oakridge, Oregon. Avalanches covered the tracks in front of them. Then avalanches and more trees covered the tracks behind them too. One hundred and eighty-three passengers. Able-bodied men and women. Infants in diapers. The infirm and the anxious. Thirty-six hours stuck. The snow was too deep to attempt a march out. There was no power in Oakridge but the train had fuel, thus heat and light. Food was limited. Diapers ran out quickly. Even when the track was cleared and the train was returning to King Street Station, there was a delay when a fire erupted on a trestle over the Columbia River and crews in fireboats had to put it out from below.

Just like the spot of the Wild Bunch’s last robbery and the slope where the train rolled into the Tye River, I want to see the earth of the story.

In sleeper cars, if you leave your door open and the curtains pulled back, you are being social, willing to receive guests. This is how I see a man in a plaid shirt and wearing an Amtrak employee nametag settle into a room near my own. He leaves his door open, too.

“Good Morning,” I say.

“Good Morning!”

“You’re working this trip?” I ask, pointing at his badge.

“Yep.”

“What do you do?”

“Food,” he says, smiling.

I like him immediately.

Josh Lynn, I learn, is an Amtrak Public Health Inspector for the west region. He covers the routes from Los Angeles to Vancouver, Canada, the inspector for all the food cars, commissaries, vendors and the yard.

“I was a chef before coming to Public Health,” he tells me. “Almost ten years. I was working at a country club in southern California. It was all banquets and I was looking for something different. Amtrak called me out of the blue and asked if I would like to join. I didn’t want to just sell snacks, but I came in and looked at the equipment and said yeah. Back then we were doing 300, 350 for breakfast every day.”

“And now you’re the food cop,” I say.

“Not the only one,” he says. “Amtrak has five food inspectors who ride the rails every day.”

We get to talking about the cook on the Empire builder, the steaks and burgers and omelets. I tell him I visited the kitchen and the cook was turning 150 meals for dinner.

“That’s busy,” he says.

He tells me about visiting kitchens, checking procedures, gloves and hairnets and ways of handling food. But then we talk about food, production kitchens, recipes sent to vendors all over the country, the steaks made to order.

We talk about last night’s cake, chocolate cake with caramel inside and nuts, just as Paul and Edith walk by on the way to their room.

“Good Morning!”

“Good Morning!”

It’s like a family reunion.

“That cake was great!” Paul says.

“Oh,” Josh says, “It’s my favorite. It’s made by a place called Sweet Street bakery somewhere in Illinois, south of Chicago.”

Paul and Edith get settled in their room, just one away from my own, and we bring each other up to speed. They wandered a bit, spent the night in an Airbnb, were anxious to get back to the train. Josh listens politely.

And then there is that deep thrumming again. We are leaving!

~~~

The scenery leaving Seattle, heading south, is industrial: warehouses, parking lots, storage areas. I am hoping the clouds break. I’m hoping to see some mountains. I put the camera down to wait.

The train passes King County International Airport, better known as Boeing Field, far sooner than I expect and I am completely unprepared. I see an old tri-tale Constellation, painted in the bright red and white Trans-Canada colors, on the ramp. Tall and slender and sleek, four big propellers, this was one of the last big designs before commercial aircraft went to jet engines. This is the airplane version of the steam locomotive.

I leap and fumble, but it goes by too fast to get a picture.

Still, I think, the look of that airplane! The moment is real. Old-school airline elegance, seen from a sleeping compartment on the Coast Starlight. The whole idea may be just a myth. But so be it. The act of travel is its own destination. Let there be beauty and romance here, too.

A bit later, Josh and I meet in the hallway, each going a different direction, when another man, in a blue shirt and tie, epaulets on his shoulders with an Amtrak logo, grabs Josh’s shoulders from behind.

“Sir, is this man bothering you?” he asks me, shaking Josh.

Josh rolls his eyes. Everyone smiles.

Dan Hensley, we learn, is our car attendant for this trip.

“Whenever you have a moment,” I say. “I’d love to talk.”

“How about right now?” he asks.

I motion to the empty chair in my room.

~~~

“I’ve been with Amtrak 30 years and 3 months,” he says. “I got out of the Army, messed around for a year. Went totally for a whole different job. At the unemployment office I wanted to be a driver for some talk show host in D.C. The lady at the unemployment office said Amtrak is hiring, do you want to put in an application? I said sure. Amtrak was the first company to call me to work and I’ve never left. Started on the east coast in 89. Left there in 92. Transferred out to L.A. after my wife got out of the Army.”

“What did you do in the Army?” I ask.

“First 30 years I was in air defense. Last five I was a medic.”

“Tell me an Amtrak story?” I ask.

“There’s so many,” he says.

“What’s the most memorable?”

“Meeting Emilio Esteves,” he says. “He’s a pretty good guy. He was in a sleeper because he didn’t want to fly. He just wanted to be off the grid for a little while. Got on at Oxnard and went to Seattle. He’s very down to earth and wonderful. At the end of the trip he asked me and another person working the lounge to go out with him.”

The intercom comes to life behind us.

“Good Morning Ladies and Gentlemen, we’ve just been told by the dispatcher that we’re going to hold because there’s a fire ahead. It is not on the tracks. Or near the tracks. But we need to let the emergency vehicles get by.”

“There’s a fire coming?” I ask Dan.

“That’s what they say.” He does not seem concerned at all.

We both look out the window at Puget Sound.

“Did you go out with Esteves,” I ask?

“No,” he says. “I made an adult decision.”

“Do you wish you would have gone?” I ask.

“I wish I would have gone,” he says. “I went home and told my wife and daughter and they’re like ‘you’re dumb.’”

“Oh, we do get jerks,” Dan continues, pointing across the hall toward Josh. Everyone laughs.

“There was this one lady,” he says, “she was like Satan’s sister. She was horrible. She was rude. She was nasty. But I just let those people go. I just leave them alone. If they need me, they can come and get me, but I’m not going to interact like anywhere else. I’ve been here a long time so I know who I can mess with and who I can’t.”

“If you had a three-year-old at home, wouldn’t this be a terrible job?” I ask.

“When I started my daughter was three,” he says. “It was fine. She enjoyed me coming home. She actually rode with me when she was like three years old. She knew the job. We were on the 10 and 6 sleepers, just the lower level where there are 10 economy rooms and six deluxe rooms. She stood right at the door of where my crew room was and she knew the routine. She’s like ‘Oh, my daddy will be with you in just a minute.’ She’d follow me when I’d explain the room. She’s like, ‘you forgot to tell them this.’ She knew the whole routine before she was five years old. But now she’s 32 years old so…”

“Tell me one more story,” I say.

“Anything?” he asks.

“Go for it.”

“It doesn’t matter if it’s graphic?”

“Not to me.”

There is a fire ahead of us. Not on the tracks, but close.

The conductor comes on the intercom but does not have any more detail than this is a concern. Not a threat, he says, but a concern because we are filled with diesel fuel.

This is not a comforting thought.

He does not say which side of the train the fire is on. Or how close.

A few minutes later he tells us we are getting close to the area of concern. There are people up ahead checking it out. It does not appear to be a large fire but close enough to the tracks to be an area of concern. We stop.

There is no announcement when we get rolling again. Josh looks out his side of the train. Paul and Edith and I look out our side. Not one of us sees any evidence of fire.

We pass the Tacoma Narrows, the site of Galloping Gertie.

An area of concern.

Suddenly, the ride has a voice-over narration. Some man is telling us what we can see out our windows, giving a history to the hills and roads and rails. A voice on the intercom tells us we might see orcas and eagles. If the day were clear, we would see mountains.

I go looking for the voice and discover a National Park Service ranger in full uniform with stiff-brim hat in the observation car. He’s a volunteer for the Trails and Rails program. He is also enthusiastic.

“The next little bit of Puget Sound,” he says, “some consider the most beautiful train ride in America!”

We roll into Olympia-Lacey. Olympia is the capital of Washington, so I expect a station of size. Instead, I see a small building set back from the tracks. Quaint, I think.

My notes tell me this station is run by volunteers who make it a point to meet every train. My notes also tell me there is a mystery here. The current station opened in 1993. It’s built on the footprint of the original station, built in 1891. But no one knows when the original station disappeared, or how, or why. No one knows if it was torn down, burned, taken for a museum on Mars. It’s not in the records. Just one day gone. A local archeology professor has students working the site.

At the stop I watch a tour group of white-haired men and women roll their baggage to the coach car.

Gene Kelly and Cyd Charisse, I think. Brigadoon.

Paul and Edith have a problem. The ceiling vent in their room cannot be repositioned and the cold air stream is strong. However, Paul travels with duct tape.

“You pack duct tape?” I ask.

“You have no idea how often I use it,” he says.

Then inspiration strikes. Dan and Paul duct tape Josh’s door, seal it shut.

“He’s not in there, is he?” I ask.

Both men pause.

A short while later, in the hall, approaching Centralia, Washington, I have a conversation with Dan. I’m on the lookout for something and I don’t want to miss it. But for some reason we sound like characters in a Samuel Beckett play or a Donald Barthelme story.

—There is an egg.

—An egg.

—The world’s largest.

—Records are important.

—It’s supposed to be something.

—To establish worth.

—I’d like to see it.

—We’d all like to see something.

—I’ve made promises, you see, to see it.

—To make note.

—To confirm the work of others.

—To hope.

My notes say the egg is visible after the station. We never see it.

“My notes say it’s after the station,” I say.

Dan looks at me. “Going which way?

Dan tells the story of a mom and dad in a room on one side of the hall, their young twin boys on the opposite side of the hallway.

“I would walk up and from outside the rooms, in the hallway, I would press the attendant call button. The kids would say, ‘What was that?’ I would say ‘Every time that goes off it tells me you’re doing something wrong.’ The kids would say ‘We aren’t doing anything!’ I would go away and then come back a little later and ring the bell. ‘Well, you’re doing something wrong,’ I’d say. Eventually they started pointing at each other. ‘He did it! He did it!’”

“Mom and Dad loved every moment,” Dan says.

Somewhere north of Portland, the train crosses a river. And as we cross, I see a motorboat cruising toward the bridge. There are two women in the bow, covered in blankets. Two men stand behind the windshield. Even though they are some distance away, even though we are moving quickly and they are moving quickly, the men raise their arms and wave, energetically, toward the train.

Why do people wave at trains?

We do not wave at airplanes, unless we are saying goodbye or hello to someone we know. We do not wave at Greyhound busses. We do not wave at minivans.

We do wave at people who drive the same car we do. Motorcycle riders will give a low salute to each other. On remote gravel roads, it’s a prairie fact that drivers will raise one finger off the steering wheel when passing someone else, just to greet some other person in the wilderness.

So, if waving is an expression of community, why do people wave at trains?

I watch the men and women in the boat. For just this moment perhaps, I believe the wave is a wave of desire. There is a train heading somewhere! The wave is a wish to somehow join the rush and adventure, to light out for the territory, to proceed onward, to boldly go. All aboard.

I have lunch with Edith and Paul and a woman named Verge. She has just retired from managing law firms and is making a long trip by herself. She was one day ahead of us on the Empire Builder and took a day to explore Seattle.

“We’re going from Jacksonville to DC to Chicago to Seattle to LA, then allll the way through Texas to New Orleans, then to DC again and back to Jacksonville,” Edith tells her.

“Why?” Verge asks.

“Because the train is fun,” Edith says. “The train is fun,” Paul repeats. “The train is fun.”

“We don’t like to fly,” she says. “It’s not fear of flying. Just the hassle and you don’t see anything. We once went to see our son in LA. For some reason the southern route wasn’t available and we were routed up through Chicago. They said it will add a day to our trip but it won’t cost us anymore. We said, Sure!”

“The geography has been super,” Paul says. “Especially from Montana on, it’s been really fun. We’d kinda seen the Midwest before, so that wasn’t unusual. It’s really flat.”

He smiles at me.

“But it was unusual starting in Montana and then into Washington and then here. This route is knock your socks off. It just gets better and better.”

“Scenery is the primary draw for us,” he says. “And we get to hang out together. We’re on vacation. We don’t have the normal things that we feel responsible for doing. No responsibility. And the people are fun.”

In Portland we have a break. Everyone gets off the train, wanders into the station, stretches arms and legs and lungs. When it comes time to board, Dan tells a lady getting on with a box of Voodoo donuts that as of January first, the railway no longer allows people to get on with donuts.

He is, of course, joking.

But then he is interrupted by someone else and the lady believes him. She walks back into the station and tries to give them away. Fortunately, she tries to give them to Josh.

“No, no, no,” he laughs, explaining the joke. She goes back to the train and discovers two people have taken her seats, just because they like her seats more than the ones they were assigned. She asks what seats they were given and they refuse to answer. I tell Dan.

“Something else to straighten out,” he says, heading that way.

“You realize this is that crew,” Dan tells me later.

We are talking about the storm last year, the avalanche and fallen trees, the 36 hours.

“Excuse me?”

“The crew that’s on board right now. We were the ones on that trip.”

I look at him dumbfounded and astonished.

“Go talk to Jimmy Lake. He’s in the snack bar.”

I head that way, shoulders bouncing off both walls, and discover James Lake, Lead Service Attendant, downstairs in the observation car. This is where the snack bar is, where the bar is too. Even though both are closed at the moment, he agrees to talk.

“Ok, well you’re going to laugh,” he says. “Actually, I had been gone for four months. So, that was my first trip back. And it was quite amazing. I mean, things are going to happen. They always do on a railway. But you never expect a long delay like that. And I’m usually pretty well prepared. But after being gone for four months and coming back I wasn’t that prepared. My mind was still working, so the creativity part was still there.”

“What was your first indication of a problem?” I ask.

“Well, everyone felt the tree hit the train,” he says. “And there were actually two. One lodged between the engine and the baggage car. And then the second one landed back, I think it was on the 12 car if I remember correctly. Stalled us right there.”

“Did you feel a weird motion, or what?” I ask.

“When you’ve been working on the rail for a long time, like most of us have, you know the difference when something’s off. And it’s like ‘okay, here we go!’ You hear the emergency brake and boom, we’re stopped.”

“How many years do you have?”

“I think fifteen.”

“That’s a couple rides.”

“We were there for quite some time. And, of course, that was my busiest point, so I really don’t’ remember much. Once we stopped everyone was like ‘Oh, they’re going to run out of stuff.’ So, it just got really busy.”

“How many days of stuff is on the train just normally?” I ask.

“Normally, you have enough for two days. And sometimes three days, just depending. I do like to back order quite a bit out of LA or even Oakridge. Especially during winter, you’ve got to be prepared. You never know what’s going to happen. Anyway, we were stuck. I really can’t remember how long we were there. Then they moved us farther toward Oakridge. That’s when we were informed that Oakridge, all the way 60 miles south, had no power anywhere. I was like, ‘We can call the grocery stores. We can get food.’ People were at the stores, but they could not leave the stores because there was no power. There was no service and of course it was a hazard to leave the train. So anyway, we were still fine. We were still serving meals.

“Hazard to leave the train?” I ask. “How deep was it?”

“By the time it finished it was fourteen, maybe sixteen inches. But it was a wet heavy snow. There was a point where people were like ‘those snowflakes are the size of houses!’ You really barely could see through it. It was really treacherous.”

“Did people try?”

“No, actually. Everybody stayed on board. We had power. We had food.”

“Do you have the authority to keep people on board?”

“If people want to leave, they can leave. But they can’t leave at points where there’s no exit that’s safe. We can’t let people off the train that way.”

“So you have the authority.”

“Yeah, it’s a hazard.”

“But the people who are claustrophobics or anxious?”

“We had a few people who had panic attacks. And down here what I did was open the window and monitor and have them sit and relax and breath air.”

“You’re all CPR trained. What about beyond that?” I ask.

“AED. And I’ve got a background in nursing and paramedic, but that’s a long time ago.”

“Nobody was injured. Nobody was hurt,” he says.

I tell him about the stories we were hearing in the Midwest on the evening news and Youtube and Facebook. The stories were everyone actually behaved well, I said.

“They did. There were 183 or 184 passengers. There were a couple of people, of course, who were upset. You can’t make everybody happy. But the time spent with one another—there were communities growing. I heard quite a bit from people when they would come in to get something. ‘You know, these people, I would never talk to them on the street. I wouldn’t even look their way. And I’m having the best time of my life.’ And because there was no cell service, except Verizon for some reason, which wasn’t many people on board, I just passed my phone around. I was like just call whoever you need to. Call your professor. Call home. There was a family trying to get back to Italy. They missed their first flight. They rescheduled. They missed their second flight. There were two people with pets. And so, the conductors were good and took them outside, because of course conductors and engineers can get off the train, so the dogs were taken care of. The dogs were fed as well.”

“What did you feed them?”

“They had water and then a rice and meat combo that I put together. Whatever I could get from here and there. And there were a lot of infants, so baby food. We did get some baby food the next day. But most parents had enough with them to get through.”

“When you say you got baby food the next day—helicopter drops?”

“No, when we were finally on the move and heading back, at Springfield I believe it was, an officer brought down a carload of water, pastries, baby food, diapers. Prior to that I was making diapers out of towels and safety pins. And I only had to make a couple, but it became a famous thing. ‘Oh My God, the guy downstairs is making diapers!’ Sorry, I got nieces and nephews, grand nieces and nephews, when you’re in a pinch you make what you can.”

“Any real jerks among the passengers?” I ask.

“There were a couple. They weren’t happy and they were people you can’t make happy. There were a few that were tweeting and texting and putting things on Youtube that just weren’t the truth. I only know of them because I had one employee that was just so angry. “Did you see what they just put on twitter?” But they were one percent of the crowd. Don’t worry about what they’re saying, I said. You know you’re doing your best.”

“The backing up bit confused me,” I said.

“There were two small avalanches ahead of us as well,” he says. “And once again there was no power in front of us, no crossings, so you really can’t move forward. All you can do is move back. Anyways, I think it was 50 hours by the time we got back to Seattle. To me it was an amazing trip. ‘Cause when you see people put their guard down, and know you can’t control a situation, it opens you up to joy. Two mornings we had kids time down here. That’s something we created. There was this lady, Megan, who was a schoolteacher. And she had her ukulele. So we just invited all the parents down with their children, and from something like 9 to 10 she would play ukulele, sing songs, tell stories. There were a couple hyper-active boys so I worked out with the boys. It was kids time.”

“What was it like,” I ask, “when you finally got to a station and people could get off?”

“It was amazing. When we got to Eugene it was nice. The red cross was there with coffee and food, water. But the whole crew was amazing. I’ve been with this crew for quite some time. We just do what we normally do.

Paul and Edith come back from playing a board game in the observation room and Dan appears shortly after, looking guilty. He says Josh is coming back, remembering they had duct taped his door shut.

Josh tries and tries, finally figures it out. Everybody starts laughing.

“He did it! He did it!” Dan says, pointing at Paul.

“It’s going to be a long night,” Josh says.

I go back to the snack bar and James and I get to talking about walking on a moving train, rolled ankles and such. He says you get used to it. I ask how often someone winds up unexpectedly in someone else’s lap. “Oh,” he says, “I call them flirting parties.”

After dinner, the train slowly climbs a steep grade. I have dinner with Verge and a young couple, early in their college careers. He works at a deli. She’s going into a nursing program. Pleasant conversation—a variation on the same topic at every meal and every table.

What do you do?

Why are you doing this?

Where are you from?

Where have you been?

We compare notes of the day. Did you see this? Did you see that?

We are all amazed.

Right now, though, I am sitting in my room. I have my feet up on the chair across from me. Outside it is approaching the golden hour of sunset/twilight. This is civilized, I think. That was the word we used at dinner. This is a tremendously civilized way to travel. I open the half bottle of wine I bought from James. A cabernet. Is it an extraordinary wine? No. Is it the perfect wine for a summer evening on a train climbing a hill in Oregon, watching the butterflies and the trees go by? Yes. Absolutely.

We head into deep forest, and I realize we are north of Oakridge. This steep incline is near where the accident happened. I can imagine the snow accumulating here. I can imagine where a tree would fall, lodging itself between cars, another tree falling at the same time farther back. The trees are close to the tracks. This makes perfect sense. Just a short while ago the landscape was open. Orchards. Bright sunshine. But now we are at elevation. We are in wilderness. There is a small path that occasionally meanders up near the tracks, but the tracks in the path are all tractor tracks. Not tires from some truck or car. This is a difficult landscape.

There are several tunnels, none of them extraordinarily long. But a couple of them—a mile, maybe? My sense of distance is off. I cannot tell how fast we are traveling.

At the top of a pass north of Chemult, Oregon (my notes say “very bare bones, central Oregon’s only station), another rail line merges from the east. There is a siding. Oddly, though, there are streetlamps on the side of the railway. Suburban style streetlamps, for places with names like Willow Lane and Orchard Avenue. I look for a picket fence and a small dog.

The tree-line approaches. Snowcapped peaks approach. A full moon is rising in the eastern sky. We’ve been without cell phone signal for what seems like hours. I think we start going downhill, but then we don’t. We are still climbing. We are moving very slowly. Creeping.

Crater Lake is somewhere just out of sight. Why are there streetlamps?

A trackside sign says Cascade summit. And suddenly a huge lake! A trailhead for the Pacific Crest Trail

A group of hikers waves at the train. Everybody waves at the train.

I’m laying on my back in my bed and the nearly full moon is rising in the east. I’m watching it out my window. From my point of view, of course, the room is stationary. But as we move to the right and move to the left, as the train banks around some curve, the moon moves in the sky. It arcs. It banks. It turns and comes back. It disappears. It’s a bit like the moon and the sun going through the sky in the Time Machine movies.

It’s really fun just to watch the moon. Right now it has disappeared past the edge of one of my windows. And now it comes back. Depending on our turn, it can come all the way from the far edge of one window to the near edge of another. Then it will freeze in the middle as the train goes down a long straight stretch of track.

It is—beautiful.

~~~

Saturday morning. Wake up, shower, have coffee in my room, breakfast in the dining car. Sit with a guy who does commercial deep-sea fishing while I have my omelet. Come back to the room.

My notes tell me that while I was sleeping, we passed Klamath Falls, where a few years ago a rider got off for a moment and thought about how much carbon a train produced versus an airplane, and coined the word flygskam, flight shame, to convey his feelings. We passed Dunsmuir, Redding, Chico, all in the path of the 2018 California wildfires. Chico borders the town of Paradise, which was completely lost.

I would not have seen anything in the dark, at speed, but I am sorry to have let these towns go by.

Coming in and then out of Sacramento, homeless shelters line both sides of the tracks. Cardboard boxes, blankets strung between trees and a fence line. I don’t see any people in them until I see one man sleeping, I hope, between a shelter and the tracks.

Dan tells me the train stopped in the middle of the night because the engineer thought he had hit somebody. Turned out to be just pants and a sweatshirt stuffed with other clothes and laying near the tracks. There’s a conductor, he tells me, who’s out with PTSD. Hitting people happens more frequently than we think, he says.

South of Davis, looking at agriculture, I am embarrassed by my ignorance. I have no idea what I’m looking at. Low fat bushes. Short skinny bushes. Trees. Certainly not wheat or corn or soybeans or sugar beets. Certainly not apple or orange or peach trees.

My face is nearly pressed to the glass trying to figure it out.

We move into wetlands and flocks of birds. There are mountains in the eastern distance. The sun rising.

Between Berkely and Oakland, we can see San Francisco off in the distance, although it’s very foggy and very gloomy. Not a good photo op.

Over the intercom, James tells us all that the bathrooms in business class have stopped working, and the compressor in the café went out. So while he has ice for sodas and such, not much. And if you need to go, you need to go to the café. Anyway! Heading toward the mountains again. Beautiful mid California scenery.

At lunch, I am joined by a lady from the JPL, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and her son. As we order, the train passes Elkhorn slough. Kayakers, paddleboarders, seals hauled out on rocks, still a gloomy and overcast day.

She is working on a satellite project with India. We laugh because there are national security requirements of not sharing strategic information with foreign countries, so there is all sort of stuff they can’t tell each other, even though they are working on the same satellite.

“We hint,” she says. “We talk around. We guess. But we’ll get it built.”

We talk about stellar navigation, how I’ve always wondered how a satellite knows where it is. Especially those satellites heading out instead of orbiting the earth.

“There is a library of star charts on board,” she says. “The sun will hit a spot on a solar panel and the computer will recognize where that bright spot or current is in the panel and that will tell the satellite where the sun is. The computer will know where the sun should be and make corrections. Other stars are dimmer and don’t generate as much current in the solar panel.”

Her son likes macaroni and cheese. He laughs about an open house at JPL where the public is invited.

“It’s more popular than bring your child to work,” he says.

From one universe to another. We come into a small valley and pass a lot of lettuce.

Men and women stand in the rows, bent over, picking by hand and then placing them on a conveyer belt while other men and women box them for shipping.

There are busses parked on the roads that border the field, I assume for transporting the workers from one field to another.

How many miles do they walk each day, I wonder, stooped and reaching?

The train follows the coastline and soon I see what I think is a NASA site. No. Space X! North of Santa Barbara by an hour or so, we pass a Space X complex. Way out here in the boonies. Beautiful coastline. Outer space! If the train stopped here I would likely not get back on. All I want is a ride.

Between Santa Barbara and Oxnard we pass a wedding on the beach. White chairs. A trellis draped with linen. A harp. All sorts of very well-dressed people, many of them barefoot. We pass a group of four people riding horses on the beach. We pass a small resort where all the staff members wave at the train. Everybody waves at the train. A pleasant evening on the beach. Misty in the distance.

Just south of Santa Barbara, there is a small island and a long pier to get out to it. Quarter mile, maybe. No one is walking it, though.

Muscle shoals!

Then a line of RVs parked along the side of the road, and it’s clear they’ve been there for some time, that they intend to stay even longer. Many of the RVs fly flags. State flags. University flags. Baseball and football team flags. Pirate flags. Smaller cars wedge between the larger campers. Just past them, picnic tables and football games on the sand. Faria Park.

Ventura Highway!

Pulling into Los Angeles, Dan gets on the intercom and thanks everyone, says it’s been a pleasure. He says this is what makes the job fun. The normal speech. He says every single one of us—except you Paul—has been a special treat. Paul, he says, your poster will be in every station across the country soon. A warning.

Laugher throughout the car.

“Take care, have fun,” we tell Verge. She’s spending a day exploring Los Angeles.

“See you tomorrow,” Paul and Edith and I say to each other.

There is no train better than the Coast Starlight, Dan says.