Just three weeks ago, I purchased A Brief History of Time, by Stephen Hawking, and less than two weeks ago, I finished the book. From what I hear, Stephen Hawking’s persona is equally linked to ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) as it is to black holes, quantum mechanics, and general relativity. The “pop culture” idea of the man is as the wheelchair-bound genius. Thus, I found it remarkably coincidental that the following Monday I was required to read a recent journal review of ALS for my neurochemistry course.

The review highlighted recent research regarding RNA dysregulation and oxidative stress as main culprits for the debilitating disease. It insisted that the two were inexplicably linked through the processes of two nuclear (i.e. pertaining to the nucleus of the cell) proteins, FUS and TDP43. The overarching theory was that oxidative stress would cause these proteins to leave the nucleus, and find their way to other parts of the cell where they would cause problems with RNA (think of it as the link between DNA and proteins). Basically, oxidative stress was destroying the cell’s ability to properly make proteins. This would in turn lead to more oxidative stress which would just start the cycle over again, eventually the cell (a motor neuron, the body’s way of telling muscles to move) would die, and thus we have ALS.

This is truly a remarkable theory, and certainly there is evidence to support it, but there is a competing theory: excitotoxicity of motor neurons. Excitotoxicity is a big word. It means that the cell is getting too much stimulation, and thus eventually dies. (Too much of anything is bad it may seem.) Indeed, the best pharmaceutical drug prescribed to ALS, riluzole, is a glutamatergic inhibitor (prevents excitotoxicity). However, even this drug is thought to extend the average life expectancy of a patient, which is only 2-3 years usually, by only a few extra months.

If the drug works at all, it must be targeting something that is causing the disease, so we can readily assume that excitotoxicity is a culprit. But the drug certainly does not cure ALS, so it cannot be giving us the full story. Perhaps the review I mentioned gives the other half of the story, though that is highly doubtful. In the end, we must agree that there is no single answer to solving this problem.

I then look back at Hawking, and his book, A Brief History of Time, and again notice a coincidence. Hawking argues that our knowledge of the universe is likewise incomplete, as there may indeed be no singular answer to the problem. He argues for more collaboration, and ultimately more research. If this is to be the case, however, I wonder if perhaps our research into the workings of the universe would be misplaced.

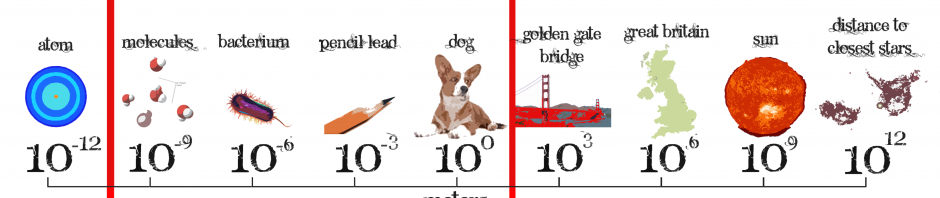

Let us imagine, for a second, what kind of world we would live in if instead of wasting hours on end mathematically modeling the trajectories of black holes spiraling into one another, we put our efforts into saving lives medically. We spend enormous amounts of time on understanding the maddeningly large, and the unthinkably small, that we forget about the in-between where lives may be saved. How is it that we can say how much slower time may progress for a relativistic traveler, but we cannot discover the causes of ALS? Could Hawking himself have, if not cured, perhaps contributed to his own disease’s salvation? Educated human beings place so much effort into things that will likely never save lives. And I constantly wonder if my own pursuit of mathematics will do “harm” to the world in the sense that I am not doing as much “good” as I could in chemistry.

Without a doubt, we (as a species) could have saved millions of lives from countless diseases if we had put our efforts into medical technology, instead of other pursuits. And yet we continue to do otherwise. Why? Indeed, there can only be one answer. Human lives cannot be quantified as “better” by the amount of time they exist. What I mean to say is, saving a life is not saving a life if one has instead thrown away one’s own life in the process. We are only here for a fleeting moment, and as such it is important for each of us to make the most of the fleeting moment. That may indeed consist of saving lives medically, but it may also consist of “saving lives” in other ways. Perhaps an article written by a journalist prompts a young boy to enter politics, wherein he pushes to allocate more money to NASA, who in turn create a nano-scale polymer to shed heat on rockets reentering the atmosphere, but indeed that nano-scale science is published and gives medical researchers the ability to create cancer-targeting drugs, wherein countless lives are saved. The journalist, perhaps dead for twenty years, has just saved lives, by doing what she loved best. A scenario like this, can be represented by the butterfly effect, which states that the smallest change in initial conditions can have unforeseeable consequences for the future.

In the end, then, we can at least agree that our actions, however we decide to make them, will certainly change, and possibly even save, lives. Stephen Hawking may likely still be bringing about his disease’s salvation, just in an obscure way. But at the same time, he is following his own path and immensely impacting the world for the better. It is not only our right, but our duty to pursue our own passions, even at the extent of others’ deaths.

Where Do We Draw the Line on Research?