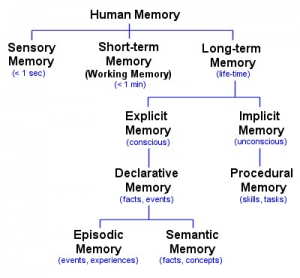

Memories make up who we are as individuals. When memories are interrupted, degraded, or inhibited, we see cases of dementia such as Alzheimer’s Disease–what we discussed last week. There are many different types of memory that people may form (Fig. 1). Explicit memory refers to memories that individuals can consciously discuss whereas implicit memories cannot be distinctly defined or stated. A type of implicit memory is procedural memory. This type of memory exists for skills and actions–like remembering how to ride a bike or play a sport. Procedural memories may also be referred to as “muscle memory” in popular language. Episodic memory is a type of explicit memory that refers to memories regarding autobiographical events–the who, what, when, where, and why. Semantic memories tend to involve facts and concepts.

This week in class, we discussed traumatic memory in regards to PTSD, Anxiety, Depression, and other psychiatric illnesses. Traumatic memory, also called somatic memory, are strong, resilient memories formed following traumatic, psychologically damaging events. In order for an individual to form a traumatic memory, that same individual has to personally experience the trauma. If a societally traumatic event happens around an individual, a memory formed for that event would be considered a flashbulb memory. As defined in 1977 by Brown and Kulik, flashbulb memories refer to emotionally charged memories formed upon learning about a public emotionally charged or traumatic event. These memories are not autobiographical in nature–they did not occur to the person, but around the person. The name, “flashbulb memories,” stems from their nature of allowing the individual to visualize themselves as they were when the event happened, as if they had taken a picture of themselves during that moment.

Although the nature of the memories may differ, flashbulb memories may be similar to trauma or stress induced memories. Originally, Brown and Kulik, 1977, hypothesized that due to their emotional strength, flashbulb memories might be formed using a unique pathway. The researchers also believed that flashbulb memories were not subject to change–that they were stronger than normal memories and not susceptible to the inevitable forgetting and reforming that other memories experience. More recent research has shown the opposite of Brown and Kulik’s claim regarding the resilience of flashbulb memories. A study by Talarico and Rubin, 2003, used a test-retest methodology to find substantial inconsistencies in flashbulb memory recall–from the initial to the latter recall of the memory.

When it comes to traumatic memories, the study of flashbulb memories has helped researchers understand memories that stem from psychological stress. Specifically, one study looked at the memories made by individuals who were not directly impacted, but lived in New York City during the events occurred on September 11th, 2001. The study assumes that the individuals created flashbulb memories of 9/11 and found, using brain imaging, that their amygdalae still showed increased activity levels three years following the events. These individuals were not at Ground Zero, but lived or worked near the epicenter of the attacks. This finding is important for the distinction between flashbulb memories and traumatic memories. Due to their similar nature, it remains unclear if molecular differences exist between the two types of memory.

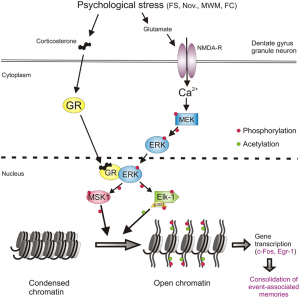

When discussing these two types of memory, their similarities seem to outweigh their differences. The major difference between the two seems to be whether the individual themselves experienced the traumatic event or if the individual witnessed the traumatic event as an outside observer. Regardless of this characteristic difference between traumatic memories and flashbulb memories, they likely utilize the same formation pathway (Fig 2). Research understands that once formed, both types of memory may lead to the onset of PTSD, Anxiety, Depression, or other psychiatric illnesses if not properly treated soon after the traumatic event. Although different treatment options exist such as pharmaceuticals like SSRIs, atypical antipsychotics, or mood stabilizers, treatment that utilizes psychotherapy tends to be more successful. Common psychotherapy treatment options include Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT), Prolonged Exposure (PE), and Eye-Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR). Each therapy aims to address and process the negative thoughts one possesses due to the traumatic event. Regardless of the treatment process, it remains important to address negative thoughts–as a result of the trauma–as soon as they appear. The earlier the intervention, the less likely an individual is to develop psychiatric illness following a traumatic event.