“Stressful events evoke a long-lasting impact on behavior”

In our society today, it is no secret that mental illness is a major topic of discussion. Mental illness disorders affect ourselves, our friends, family members, colleagues, and more. Specifically, anxiety disorders are the most prevalent mental illness in the US. 18.1 percent of adults suffer from this illness. 70 percent of adults in the US have experienced a traumatic event at some point in their lifetime. An estimated 8 percent of adults have PTSD in the US at any given time. These statistics show that there are some underlying factors with these illnesses. Is it all environmental, genetic, only in our brain, or a mix of everything? Below, we will explore parts of the brain that are in overdrive when dealing with illnesses such as PTSD and anxiety.

When a person is under stress, research has found that learning and memory processs can often get messed up. The area of the brain that have shown this happening is the limbic system, which is made up of the thalamus, hypothalamus, hippocampus, amygdala, and the fornix. The area to focus on with anxiety but especially with PTSD is the amygdala. The amygdala is responsible for the preception of, response to, and memory formation of emotions, especially fear. This means that when a person experiences a negative emotion that is associated with a traumatic event, their amygdala will be sure to remember it. Psychologists often call this idea emotional learning. For example, if a child gets bit or attacked by a dog, that is clearly a traumtic childhood event. The amygdala will take the negative stimulus of getting bit by a dog and store that traumatic memory fairly quickly. The negative emotions that were felt during this event are then associated with the dog biting event, which includes dog barks, dog parks, and even simply seeing a dog in public. The amygdala is a major reason for why getting bit by a dog as a child can cause someone to have a phobia of dogs for the rest of their life.

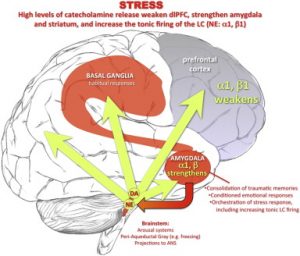

With PTSD and the amygdala, these two words go hand in hand. Several studies have shown that in patients with PTSD, there was hyperactivity, or a large increase in activity, in the amygdala when stimuli were shown that were connected with their traumatic experience. This stimuli can range from pictures from an event, talking through the specific details of the event, noises, etc. This hyperactivity occurs directly after the traumatic event as well as during sessions where triggering stimuli is shown. This all is basically general knowledge. What is not is that in stressful or traumatic events, many parts of the brain are inhibited or weakened, such as the prefrontal cortext. The amygdala is opposite. Because this part of the brain consolidates so many of these traumatic memories, when the memories are triggered, the amygdala springs in to action.

weakened, such as the prefrontal cortext. The amygdala is opposite. Because this part of the brain consolidates so many of these traumatic memories, when the memories are triggered, the amygdala springs in to action.

A more recent finding with these PTSD brains and the amygdala is that the same hyperactivity that was found when the patient was shown associated stimuli was also found when shown material unrelated to their event. This included pictures of random people with fearful expressions or event doing oddball, continuous tasks. This finding may suggest that brains with an overactive amygdala may be over-resoinding to inputs that are not deemed dangerous or traumatic to a brain that does not have PTSD. My question is this: In PTSD brains, can there be such a thing as a happy medium of your amygdala detecting what is truly dangerous and what is not? PTSD is a horrible illness that effects far more than those traumatic memories that are stored away.

It is already known there are many factors that contribute to PTSD and anxiety disorders. Traumatic events, memory consolidation, and the amygdala are only a few of them. Sometimes, diving into one part of the big problem makes it seem less daunting. If a researcher can figure out how to keep the amygdala to a normal activity rate, who knows what else could be solved?

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352289514000101

https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/d3e0/f4c57b4cd63ec0ee1d2a447bef25d960b65c.pdf