ALS, often known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a debilitating and horrific disease. It is defined as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and is a neurodegenerative disease that affects nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord. In short, ALS targets motor neurons in the brain and spinal cord which causes them to deteriorate and eventually die, leading to loss of control of voluntary muscle movement. This is the main reason why ALS is so debilitating is because people with this disease eventually lose their ability to eat, breathe, move, and speak independently.

What I found most peculiar about this disease is the varying amount of knowledge that common people in our society have. It’s different than cancer or other more common diseases that seem to be a typical topic of conversation surrounding disease. With ALS, it seems to be that if you have a family  member or person in your life who has been affected by ALS, then you know a lot about the disease and the difficult effects it has on a family. But, if that is not the case, it seems as thought people do not know too much about the specifics of the disease. This is an odd observation because ALS has been brought into the spotlight through the great Stephen Hawking, through movies, and social media, like “Tuesdays with Morrie”,

member or person in your life who has been affected by ALS, then you know a lot about the disease and the difficult effects it has on a family. But, if that is not the case, it seems as thought people do not know too much about the specifics of the disease. This is an odd observation because ALS has been brought into the spotlight through the great Stephen Hawking, through movies, and social media, like “Tuesdays with Morrie”,  and the Ice Bucket Challenge video phenomenon. When it is an encouraging sign that ALS is at least being talked about, the part that no one wants to talk about if almost always overlooked: the end.

and the Ice Bucket Challenge video phenomenon. When it is an encouraging sign that ALS is at least being talked about, the part that no one wants to talk about if almost always overlooked: the end.

End of life care with ALS is difficult for a few reasons. First, there is no set structure or correct drug to use to help. This is because the progression of ALS can vary from being quickly deteriorating or drawn out over many months. The ALS Association as well as many palliative care sites suggest the discussion of end of life care beginning as soon as they feel comfortable after the loved one has been diagnosed. In addition, they suggest to start hospice when the person has six months or less to live if the disease progresses as it has been. This conversation is not an easy one to have, but is highly encouraged to have earlier on in the disease so that the loved one can have a say in treatment, care, etc.

An interesting study was done a few years back where they had 50 caregivers complete a survey about ALS patients’ last month of life. Some of the study’s findings are listed below:

- Most common symptoms: difficulty communicating (62%), dyspnea (difficulty breathing) (56%), insomnia (42%), and discomfort other than pain (48%).

- They reported an advance directive (medical treatment, living will, etc) was completed by 88% of patients

- 2/3 of patients were enrolled in hospice

- Compared to nonhospice patients, hospice patients were significantly more likely to

- 1) die in their preferred location

- 2) die outside the hospital

- 3) receive morphine

This study is not the only of its kind. Many scientists, psychologists, and sociologists alike are looking into analyses and reviews like this one to collaborate on how to better the end of life care for people with hospice. The study did conclude with saying that “many patients with ALS still experience distressing physical symptoms in the last month of life, despite enrollment in hospice.” It is gravely difficult to create a comforting setting for someone in their last month of living with ALS. However, hospice is a great option to get as close to comfort as they can.

So, what’s next? I think that the topic of ALS can be brought up more in science classes in secondary education and in conversations about societal diseases. Getting into the details of what the disease actually is is an important way to begin discussion of how to help those suffering and those caring for their loved ones who suffer.

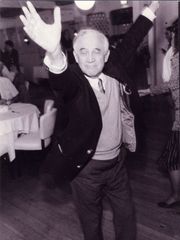

As put beautifully by Morrie Schwartz about his life…

“The truth is, once you learn how to die, you learn how to live.”

For more information:

http://www.alsa.org/about-als/facts-you-should-know.html