Addiction today is such a common issue, and everyone seems to have a different take. People talk about whether it’s a disease or choice holding to their convictions as if letting go would send them to drown deep in the see. We see “addicts” as untrustworthy, lacking impulse control, and self-destructive, but when we look at the science it is undeniable that this thing we call addiction is so much more than just a consequence of choice or a disease with a straightforward treatment. Addiction is complex, so treatment must be as well.

Dopamine: Methamphetamine, Heroin, and Cocaine

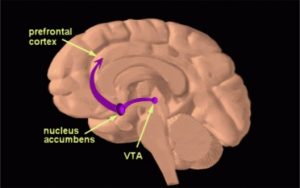

Let’s begin with what drugs do in the brain that makes them “addictive.” Specifically, methamphetamine, heroin, and cocaine all have similar consequences in the brain. Each drug acts by causing the brain to release excess dopamine. Dopamine is a neurotransmitter often thought of as a “happy” chemical in the brain. In reality, it’s a little more complex. Dopamine is largely responsible for motivation and reward which leads to the high that a drug provides. Drugs like cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine active the brain’s reward pathway in the VTA and nucleus accumbens. This means that the activity of using is reinforcing to the brain. After activating this pathway, people want to do it again and again because it is motivating and rewarding. Any addict will tell you that drugs became the most important thing in their lives. They chose is over everything else.

So, why are some drugs more addictive than others?

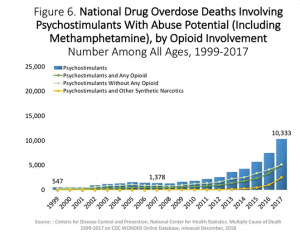

This is where complex neuroscience can be broken down into a few simple principles. Cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine all cause an increase of dopamine in the brain. The method of action, though, is quite different. Cocaine and heroin act on just one step in the path for dopamine to be released and absorbed in the brain. Methamphetamine, on the other hand acts on all these steps in addition to a few more. More dopamine leads to a stronger high and more motivation and reward feelings. Now, we can all agree that lots of happy feeling would be appealing, but we aren’t all addicted to these drugs. Even more important, not all who use these drugs become addicted to them. According to the CDC, approximately 0.6% of the population used methamphetamine while 0.4% had some kind of use disorder. Despite being one of the most addictive substance known about in modern day, not everyone became addicted.

Why do some people get addicted and others don’t?

This is where the answer gets rather complex. Addiction is caused by physical changes in the brain as a result of long-term use. Dopamine is what is referred to as an excitatory neurotransmitter. This means that release of dopamine in the brain causes a series of actions to occur rather than inhibiting action that is already occurring. When excess dopamine is released, parts of the brain are overstimulated. This overstimulation leads to structural changes in the brain. These structural changes are what “defines” addiction from a neuroscientific perspective.

What do we do?

There really is no perfect solution to a problem as complex as addiction. However, there are a few vital pillars in combatting the problem. The first is education. Programs in schools today attempt to scare people about the use of drugs. They don’t educated people on what drugs actually do and the scare tactic, quite frankly, doesn’t work. Instead, education needs to revolve around the problems discussed above. Predisposition and understanding of your personal risk are vital to preventing addiction. Another less common approach is decriminalization. Portugal first decriminalized drugs in 2001 after the devastation of the opioid epidemic. Prior to 2001, Portugal had similar policies to America; drug education was minimal and highly criminalized. When the law went into effect, 1% of the population was addicted to heroin. Drug deaths have decreased by more than 4 times and new instances of HIV/AIDS as a result of drug use has dropped 95%. It is important to acknowledge that decriminalization is not legalization. Instead, personal use of a drug requires an assessment to determine whether treatment or a fine is the best course of action. Selling of a drug and possession of large amounts with intent to distribute is still illegal in Portugal. Such a complex problem warrants a rather complex solution, likely requiring a substantial shift in social perception and desire to help rather than judge.