Aging.

It’s a word that most of us don’t like to think about. For some, the idea of growing older is a scary thought, and for others it exists only in the back of the mind until the future arrives. Bottom line is, aging often gets a bad rap. And here’s a shocker – just like you, your brain ages, and once it hits its own point of “retirement,” the natural cognitive decline associated with aging is, unfortunately, irreversible.

End of story? No! You probably didn’t come to this article to hear about all the bad stuff that comes with this natural, inevitable process, so what’s the deal? Well if you haven’t guessed yet, there is one aspect of getting older that many of us look forward to. Yup, that’s retirement. We might dream about our future selves living carefree lifestyles – never-ending days of no work, lounging around at home, or worldwide traveling without a care in the world. But in order to achieve this lifestyle, there is (like in everything else) a monetary factor. You might be familiar with the concept of retirement funds and how important they are for making the future as comfortable as can be. As for your brain, fortunately, recent research suggests that there are numerous activities that can enrich your thinker and significantly lessen the impacts, or at least slow the effects of, cognitive decline and even neurodegenerative pathologies. As it turns out, being exposed to more of these things early on builds into a special “reserve” (almost like a retirement fund!) that the brain can draw from to function more ‘comfortably,’ if you will, even as it enters its own stage of retirement. So let’s get to it!

The Brain’s Reserve – What is it?

Your brain’s reserve can be divided into two categories – cognitive reserve and brain reserve. Though they are quite similar and both beneficial in the long run, the differences between the two should still be noted.

- Brain Reserve – The available “hardware” (neurons, brain cells, mass, matter, connections, overall volume, etc) your brain has. Like most things, more is usually better. Harvard Medical School gives this useful analogy: “Just like a powerful car that enables you to engage another gear and suddenly accelerate to avoid an obstacle, your brain can change the way it operates and thus make added resources available to cope with challenges.”

- Cognitive Reserve – Your brain’s ability to use existing “hardware” in the brain reserve to cope with or adapt to changes, such as those seen in neurodegenerative diseases or age-related decline. Below are some examples of cognitive reserve functions that can be boosted by enriching the brain’s neuroplasticity (capability to change)

- Adult neurogenesis – Formation and differentiation of new neurons, even into adulthood (previously believed to be possible only in children).

- Gliogenesis – Proliferation of supporting, non-neuron brain cells (glial cells) that can help with cleaning up waste, adding structural support, and protection.

- Angiogenesis – Generation of new blood vessels that can increase blood supply and thus oxygen to the brain.

- Synaptogenesis – A form of neuroplasticity where existing neuronal ‘connections’ (synapses) are modified, or more synapses are formed. This is what you think of when you hear more brain connections.

To learn more about cognitive and brain reserve, visit this article here.

The link between the two is quite clear – available brain reserve can allow for more cognitive reserve functions to take place, and increased cognitive reserve can help build on to brain reserve. It makes sense, really. If brain matter and neuronal synapses are lost with cognitive decline, then having more “stuff” for the brain to work with will mean less information lost when things start falling apart, and an increased capability to use what’s left to make up for the loss. In neuroscience terms, the building a brain reserve is “neuroprotective” (quite literally ‘protects the brain’) against the effects of such degeneration.

Just like a powerful car that enables you to engage another gear and suddenly accelerate to avoid an obstacle, your brain can change the way it operates and thus make added resources available to cope with challenges.

Building the Reserve

Great, so now you’re probably wondering – how can I ‘add funds’ to my brain’s reserve, so I can save for those rainy days? Luckily, there are many different forms of enrichment that can help the brain add hardware and increase its adaptability. Although a part of brain reserve is genetic (how much brain capacity and matter you’re born with), research on animal models increasingly points towards the importance of an enriched environment. Continuously doing these activities throughout one’s life can help enhance the reserve:

- Physical exercise – voluntary exercise has been found to increase cell proliferation and survival rates in the brain by enhancing the production of brain growth factors, called neurotrophins. Works best when paired with a good diet.

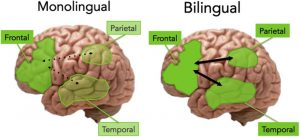

- Bilingualism – learning a new language is no easy feat, but that’s why it’s so good for your brain! Lifelong bilingualism has been found to decrease the effects of Alzheimer’s and general cognitive decline. In fact, in some studies, bilingual individuals with severe atrophy in the brain were found to out perform monolinguals with less atrophy in cognitive tasks!

- Education and Cognitive Training – This one’s pretty obvious. The more you use your brain, the stronger it gets. Being a lifelong learner constantly stimulates your brain to make new synapses and utilize its hardware for storing information and memories. Though not 100% proven, other mentally stimulating activities such as reading and doing puzzles has been associated with building the reserve. Learning is associated with better cognitive, memory, and language capacity into old age.

- Social engagement – Meaningful social engagement that allows for self-expression is shown to be a crucial part of an enriched environment. This can mean anything from engaging with friends, being part of a group or team, or participating in consistent volunteer or charity work. In some studies, those who were divorced, widowed, or single were found to have a higher likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s or dementia.

- Music and learning an instrument – They say music is like another language, and that holds true for the cognitive reserve as well. Learning an instrument is a mentally stimulating task that can help build your reserve.

And that’s definitely not all. For more about building the cognitive reserve and its neuroprotective effects, you can visit this handy article here.

The Reserve at Work

The bottom line is, keep the brain busy, and it will grow. But how does all this magic happen? The mechanisms and proposed pathways that occur in building the reserve are numerous and depends on the type of enrichment, but most of them have been linked to boosting levels of neurotrophins, which are crucial in growth and development of the brain, and to some extent regulating the neurotransmitters (communicating substances of neurons). For example, physical activity requires high energy metabolism, which places demands on the liver. Mitochondria (yes, the powerhouse of the cell!) in liver cells work hard to metabolize energy, and in doing so create a substance called DBHB (a type of ketone). This is not only used as an energy source of the brain, but has also been found to promote gene transcription of BDNF (a type of neurotrophin) by blocking an enzyme that would normally down regulate the process (if you’d like to learn more about the DBHB hypothesis, refer to the link above, in ‘Physical exercise’)!

With that said, it’s no surprise various studies show that those who invested into building their cognitive reserve displayed less cognitive decline, even in patients with Alzheimer’s, dementia, and even Parkinson’s and other usually fatal pathologies. We are quick to consider all the inevitable negatives that come with such disorders and diseases, but the cognitive reserve gives us hope that something out there exists to combat the outcomes.

But whether a dementia patient or a college-age student, everyone can benefit from enriching their mind. At the end of they day, the body operates on a very much “use it or lose it” basis, and unfortunately, that holds true for the brain as well. But by stimulating and giving the brain more resources to work with, even well into its own days of retirement, we can have some peace of mind in knowing that not all is lost with the passage of time.