Rates of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) are rising in the U.S., and as a result, scientists are scrambling to figure out what is behind this increase and what we should do about it. A neurological disorder that varies widely in presentation and severity, Autism is broadly defined by the CDC as a disability “that can cause significant social, communication and behavioral challenges.” Since the 1990’s, autism prevalence has shifted from 1 in 150 children to 1 in 69. This may be caused by changes in diagnostic practices, such as the inclusion of Asperger’s into the Autism spectrum and looser diagnostic criteria, but a variety of other factors have been proposed as well.

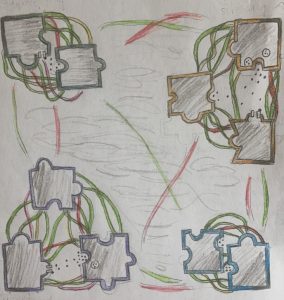

Neurochemically, there are many proposed mechanisms that lead to the development of ASD. One of the most prominent hypotheses of pathophysiology involves abnormal neuroconnectivity, where neurons are overconnected within local circuits but underconnected across brain regions further apart, possibly due to an initial misplacement and impaired removal of unneccesary neurons during development. An imbalance of glutamate and GABA may also be involved, resulting in a net overexcitation of certain brain areas that would help explain the repetitive behaviors, seizures, sensory processing difficulties and social impairments commonly seen in Autism. Genetics, environmental factors and neuroinflammation, along with components, are additional aspects of autism development that have been demonstrated through research.

People with Autism often experience life differently from neurotypical individuals, but to what degree does this warrant treatment or interventions? A fairly convincing argument has even been made by some that the occurrence of ASD within a population provides evolutionary benefits, with common autistic qualities such as enhanced memory and heightened perception contributing to the specialization of roles that further society. However, I have worked with several dozen teens and adults with Autism at a therapeutic recreation program, many of whom on the more severe end of the spectrum are unable to independently care for themselves or communicate verbally. Especially without the right type of support system, challenges like these can make it difficult to connect with others.

I am by no means an expert on ASD treatment, but my view is this: we should help individuals with ASD foster skills that will directly improve their quality of life, such as communicating their needs and thoughts they want to express to others. However, we should spend just as much energy toward creating an environment where they feel free to be authentically themselves. This is both by helping those around them learn how to best support their needs, but also by teaching society to accept and integrate individuals with ASD into their community.

When it comes down to actual treatment decisions, things can get tricky. Do therapies such as Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) help children with Autism “overcome” their symptoms? Or are there aspects of ABA that force children with Autism to assimilate to societal expectations in ways they may not need to? Different medications/therapies may pose similar ethical dilemmas. Given the wide range of symptom presentation and severity, it may be best to have a variety of treatment routes and options as well. I don’t have the answers to questions like these, but I hope that someday we will. In the meantime, we each play a part in creating a world where anyone can thrive.