The brief second of stillness immediately before the first downbeat is my favorite part of an orchestra concert, both as a cellist and as an audience member. So much goes into creating this single moment, even discounting the months of preparation of the orchestra and years of training of each member. The anticipation that hangs in the hall thick enough to cut, every musician breathing together, the eyes of every player on the conductor, the feeling of resistance as my bow grips the strings of my cello, and the silence of the audience’s anticipation for great music create a beautiful, liminal transitory tension that is, quite frankly, nothing short of addicting, even if it only lasts for a moment. I’ve played cello for the past ten years and I have yet to tire of that feeling. Yet, as interesting as that moment is, what goes on in the brain once the music starts is even more complex.

What listening to music does to the brain

Music is really cool. I freely admit that, as a music lover and musician, I’m biased and unable to objectively assess my own claim, but I think that my assertion is true and that I can convince you of that.

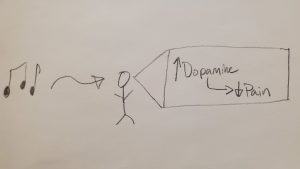

Did you know that music can reduce pain by activating the dopaminergic reward pathway (figure 1)? In fact, this reward pathway involves endogenous opiate signaling, which helps explain the pleasurable feeling you get from listening to your favorite Taylor Swift album on repeat and helps explain why we return to our musical favorites. While I doubt that this can fully explain why I’ve listened to the same Dear Evan Hansen song 59 times this year or why I spent over 27 hours listening to Vance Joy in 2019, I do think it’s clear that dopaminergic reward pathway signaling plays a role in bringing us back to our favorites.

Figure 1. Graphic showing that music causes increased dopamine release in the brain, leading to decreased pain sensation. (Strickland, Artstract #3).

Did you also know that music can help reduce stress and even help reduce the amount of anesthetic needed in surgery? This is probably the most interesting effect of listening to music that I’ve learned about to date. This impact is mediated by reducing stress hormones released along the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Research shows that listening to relaxing music helped lower cortisol levels more rapidly after exposure to stress and prevented stress-induced increases in blood pressure and heart rate.

Importantly, the experiences of listening to music and performing music are incredibly different in terms of their impacts on the brain. While listening to music has the effects discussed earlier, making that music is even more involved. As Barrett, Ashley, Strait & Kraus describe in their 2013 article Art and Science: How Musical Training Shapes the Brain, “To be a musician is to be a consummate multi-tasker. Music performance requires facility in sensory and cognitive domains, combining skills in auditory perception, kinesthetic control, visual perception, pattern recognition, and memory.”

So that begs the question: How does musical training change your brain?

Our brains are highly plastic. Not literally. What I mean by that is that our brains constantly change in response to our environment and choices and musical training, similar to how exercise builds muscle mass and endurance, creates a few very interesting functional and anatomical changes. Specifically, instrumental musicians have more gray matter in the somatosensory, premotor, superior parietal, and inferior temporal areas of the cortex that correlate with their level of skill. Additionally, musicians show increased corpus callosum volume. The corpus callosum functions as the bridge between the left and right hemispheres of the brain. This suggests that musicians may have increased connectivity between the left and right hemispheres. Interestingly these anatomical differences facilitate more advantages than mere musicality. Research has also demonstrated that musicians’ more efficient audio-motor learning ability enables them to more accurately pronounce foreign languages and improves their spatial tactile acuity.

So, what does this all mean?

First, taken together, these data indicate that music is incredibly powerful.

Second, because music can be learned and taught, it’s clear that the benefits of being a musician can be realized by all if people are given the opportunity to learn. This, of course, opens the much broader discussion of equity and access to music – especially at early ages in public education. I simply would not be the musician and human I am today without my music instructors.