Understanding PTSD Through a Molecular Lens

10-20% of the population develops a stress disorder after exposed to traumatic, life-threatening events.[1] PTSD is a big problem in America, and it affects roughly 3.5% of U.S. adults yearly. It’s estimated that one in eleven people will be diagnosed with PTSD at some point in their life.[2] Many people know someone who is affected by PTSD. Luckily, Dr. Reul wrote a wonderful review paper on the subject. I will try and distill some of the most salient parts of his research and explain the cellular mechanism of PTSD and the role exercise has in PTSD treatment.

Cellular Cause of PTSD

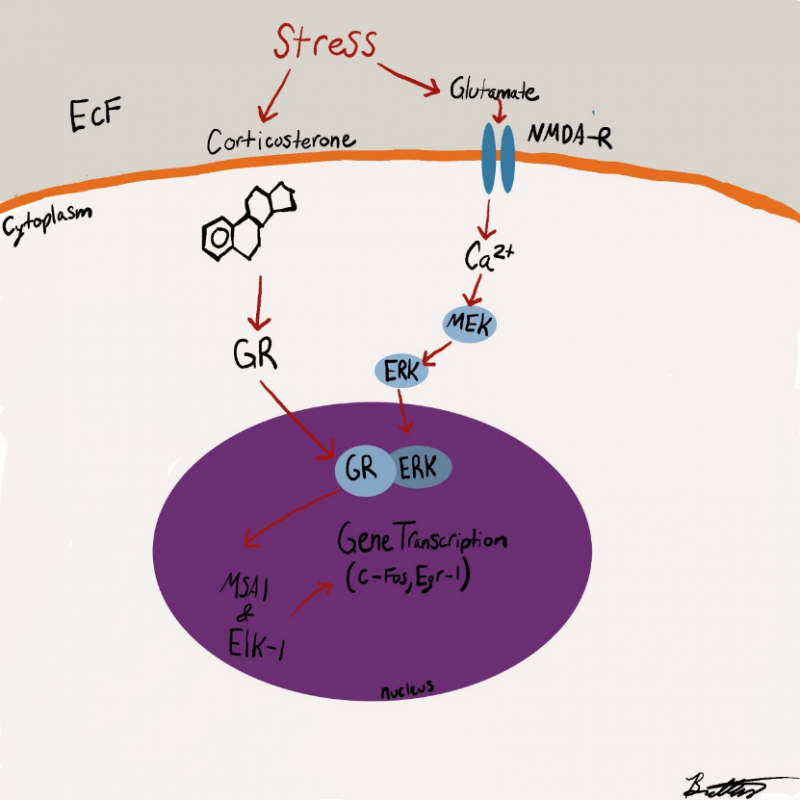

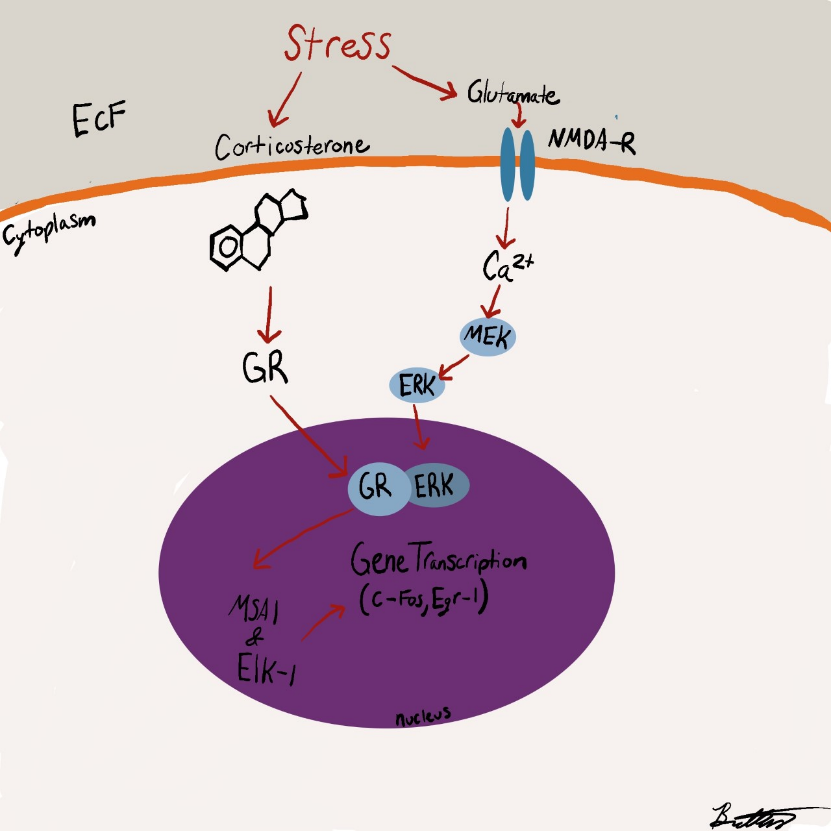

The following description of the neurochemistry of PTSD can be confusing, so be sure to follow along with figure 1 below.

PTSD begins when a psychological stress is noticed. This causes markers of stress in the brain (like corticosterone and glutamate) to increase in concentration. These two signaling molecules act on different parts of a cell due to the nature of their atomic makeup. Because corticosterone is non-polar, it is able to go through the cell membrane and bind to a glucocorticoid receptor (GR). Conversely, glutamate is polar and can’t cross through the cell membrane.

Figure 1. PTSD Pathway

Luckily for glutamate, it’s receptor (NMDAR) is located on the outside of the membrane so it can bind without any issue. Once glutamate binds to NMDAR, NMDAR goes through a change in shape that allows for Calcium ions to travel into the cell. This causes a signaling cascade resulting in the activation of an enzyme called ERK. ERK is then able to bind to the activated GR. This ERK-GR complex then moves into the nucleus (where DNA is stored) and activates two final enzymes MSK1 and Elk-1. These final enzymes cause gene transcription that results in consolidation of memories associated with the stressful trigger.

Application of the cellular mechanism to the real world

Whew! Now that we have the basics understood, we can begin to understand why PTSD occurs. The current hypothesis is that the previously described pathway is sent into overdrive by the stressful event. In short, there is too much activation of GR and NMDAR leading to consolidated memories that are too salient. This explains why something as innocuous as an alarm clock can trigger someone’s symptoms of PTSD.

For example, pretend someone has witnessed a horrible, loud car crash. This causes immense psychological stress, and their brain is bathed in a neurochemical slurry of corticosterone and glutamate. This is going to lead to extreme memory consolidation of the car crash. One of the theories on how memories are stored is called the hierarchical model. You can learn more about it here. Basically, the theory posits that thinking of one attribute of something will prime the memory of it (e.g., thinking of wings, flight, and feathers makes one think of a bird).[3] Say one of the things you associate with the car crash is loud noise. Now when you are primed to think of a loud noise by your alarm clock, this triggers the memory of the car crash causing you to re-live that painful moment.[4]

That makes sense! How about treatment? Is there anything we can do to prevent or treat PTSD?

There are a few things one can do to prevent PTSD. The review paper found that rats who voluntarily exercised had increased neurogenesis and had part of the intracellular cascade of PTSD inhibited.1 Several other studies found that increased cytokines (a marker of stress) in the blood of soldiers before they went off to war led to an increased risk of their developing PTSD.[5] This suggests that finding ways to destress and lower cytokines in the body may be neuroprotective for PTSD.

Closing Remarks

PTSD is a widespread issue, but it’s not an insurmountable problem to overcome. As more people learn the underlying cellular mechanism, the more innovative treatments and preventative measures will be discovered. Until then, exercise and reducing stress in our lives seems to be the best way to prevent PTSD.

Sources

[1] Johannes, M. H. M. eR. (2014). Making memories of stressful events: a journey along epigenetic, gene transcription and signaling pathways. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00005

[2] “What Is Posttraumatic Stress Disorder?” What Is PTSD?, American Psychiatrics Association, 2020, https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/ptsd/what-is-ptsd#:~:text=PTSD%20affects%20approximately%203.5%20percent,as%20men%20to%20have%20PTSD.

[3] “Top 3 Models of Semantic Memory: Models: Memory: Psychology.” Psychology Discussion – Discuss Anything About Psychology, 11 Mar. 2017, https://www.psychologydiscussion.net/memory/models/top-3-models-of-semantic-memory-models-memory-psychology/3095#:~:text=Hierarchical%20Network%20Model%20of%20Semantic%20Memory%3A&text=are%20organised%20into%20a%20hierarchy,logically%20related%20and%20hierarchically%20organised.

[4] https://www.google.com/url?sa=i&url=https%3A%2F%2Fcommons.wikimedia.org%2Fwiki%2FFile%3AHierarchical_Model_Mental_Lexicon.png&psig=AOvVaw1CxCYu7sAQA30ZG_rZG3lJ&ust=1634767608200000&source=images&cd=vfe&ved=0CAsQjRxqFwoTCNCYrKi-1_MCFQAAAAAdAAAAABAD

[5] Neylan, T and O’donovan, A (2019). Inflammation and PTSD. PTSD Research Quarterly. 29(4).