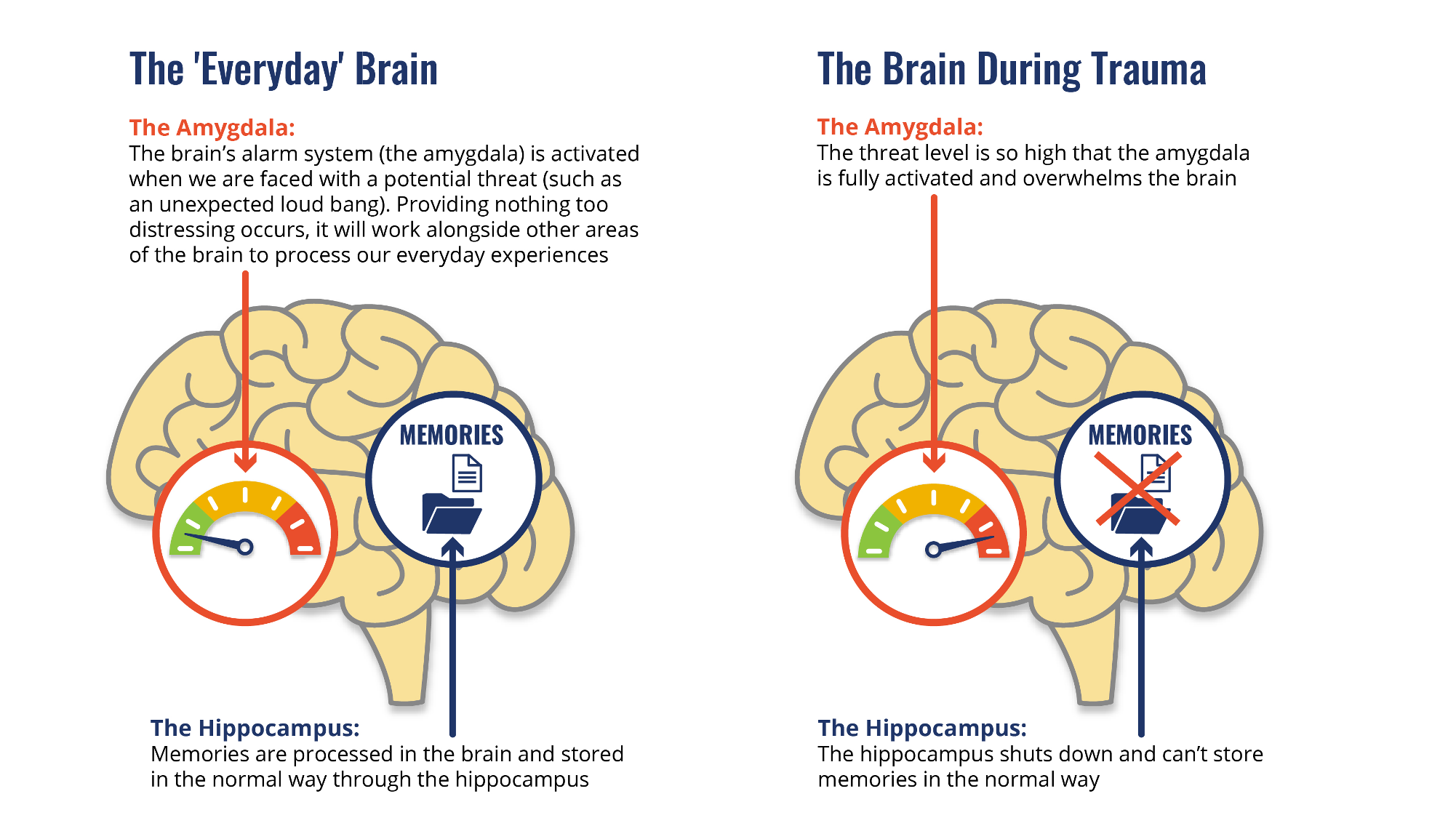

Review of “Making memories of stressful events: a journey along epigenetic, gene transcription, and signaling pathways” by Johannes M. H. M. ReulThe article by Reul explains how the brain forms and stores memories of stressful events. It takes a deeper look into the molecular parts of this process. He outlines how exposure to stress activates signaling pathways (particularly through glucocorticoid hormones and noradrenaline) that lead to epigenetic modifications and gene transcription changes in neurons, especially within the hippocampus and amygdala. These biological shifts affect how memories are formed, consolidated, and retained, which then often leaves lasting marks on an individual’s mental health. Reul has an important point in his paper that stress memory formation is not simply a switch that turns on or off, but a complex process that varies depending on the intensity and duration of the stressor, as well as individual genetic and environmental factors [1].

The Biology Behind PTSD and C-PTSD: Stress Leaves a Mark

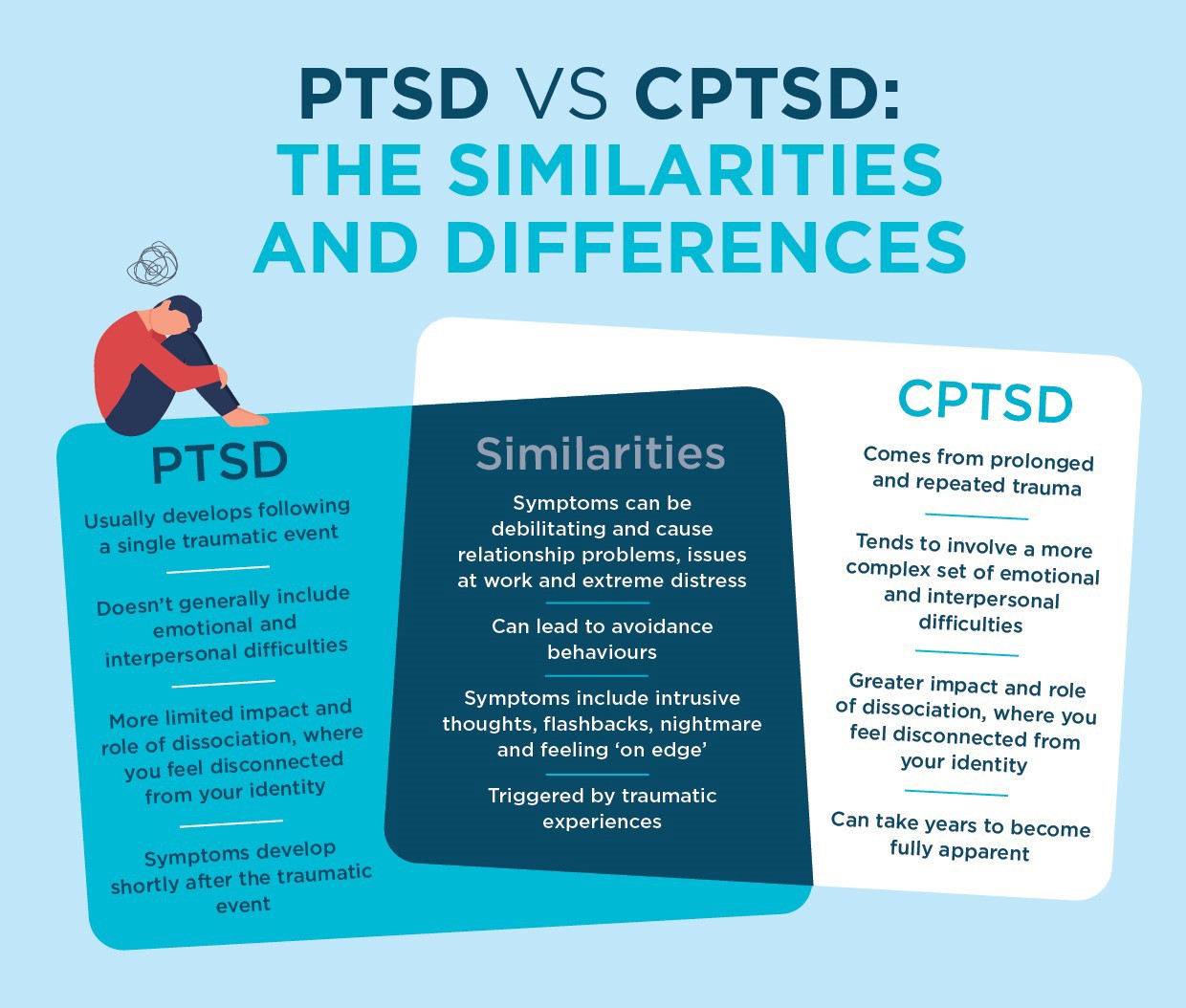

Stress is something we all know, to varying degrees. A traffic jam, a missed deadline, or a tense conversation are all moments that come and go. But what happens when stress doesn’t just pass? What happens when it affects the biology of our brains? This is the core of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and Complex PTSD (C-PTSD), where memories of trauma don’t fade, but persist. They are vivid, intrusive, and disruptive [2].

This matters because millions of people globally live with PTSD or C-PTSD, often silently [3]. Veterans, survivors of abuse, refugees, and even those exposed to chronic stress in childhood or adulthood carry the weight of painful memories that persist. These aren’t just psychological burdens. They are deeply biological and rooted in how our brains process and encode trauma at a molecular level.

Understanding this is crucial, because trauma isn’t a rare event. It’s a public health issue at this point in society. The science behind stress memory formation, like the work detailed by Johannes Reul, reveals not only the how behind trauma memory, but also the why (why some people recover while others remain stuck) [1].

This understanding is far from complete. PTSD and C-PTSD can be difficult to treat. Traditional talk therapy and medication can help, but not for everyone. The brain’s response to traumatic stress is very nuanced, involving cascades of molecular signals, epigenetic changes, and structural shifts in brain areas like the amygdala and hippocampus. For people with C-PTSD (often linked to prolonged, repeated trauma like childhood abuse rather than PTSD’s acute event), the challenge can be much more complex. Their brains don’t just react to a single traumatic event; they adapt to a world in which trauma is the norm [2].

Memory is Key

But the core issue lies in memory: why are these traumatic memories so persistent? Why do they resurface without warning? Why are they embedded so deeply in the fabric of who we are?

The insights from Reul’s research outline the journey from stress exposure to lasting memory through molecular biology. He reveals potential intervention points. For instance, if we can modulate how stress hormones affect gene transcription right after a traumatic event, could we prevent PTSD from developing? Could future therapies target epigenetic markers to “soften” traumatic memories without erasing them entirely [1]?

This research doesn’t just decode how trauma shapes memory. It also looks at a possible course toward healing. It tells us that trauma is not just stored in the psyche, but also in the synapses, genes, and proteins that shape our brain’s response to the world [4].

Societal and Future Impact

So what does this mean for us, for society, for the future? It means rethinking trauma care as not just a psychological issue, but a neurobiological one. It means investing in early intervention, especially for children and communities exposed to chronic stress. It raises powerful questions: Can we “edit” traumatic memories without compromising identity? What ethical challenges arise from altering memory? Would we one day vaccinate against PTSD?

And here’s the takeaway: Trauma is not just remembered- it is encoded. Understanding the biology behind PTSD and C-PTSD allows us to move beyond stigma and into a future where treatment is personalized and preventative. If the brain can change in response to trauma, it can also change in response to care.

Let’s keep asking questions. How do we turn understanding into healing? And let’s stay curious, because the science of memory isn’t just about the past, it’s about shaping the future.

[1] Reul, J. M. H. M. (2014). Making Memories of Stressful Events: A Journey Along Epigenetic, Gene Transcription, and Signaling Pathways. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00005

[2] Danfeng Li, Jiaxian Luo, Xingru Yan, & Yiming Liang. (2023). Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (CPTSD) as an Independent Diagnosis: Differences in Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-Being between CPTSD and PTSD. Healthcare, 11(1188), 1188. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11081188

[3] Guideline Development Panel for the Treatment of PTSD in Adults, American Psychological Association. (2019). Summary of the clinical practice guideline for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults. The American Psychologist, 74(5), 596–607. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000473

[4] Herman, J. (2012). CPTSD is a distinct entity: comment on Resick et al. (2012). Journal of Traumatic Stress, 25(3), 256–7; discussion on 260–3. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21697