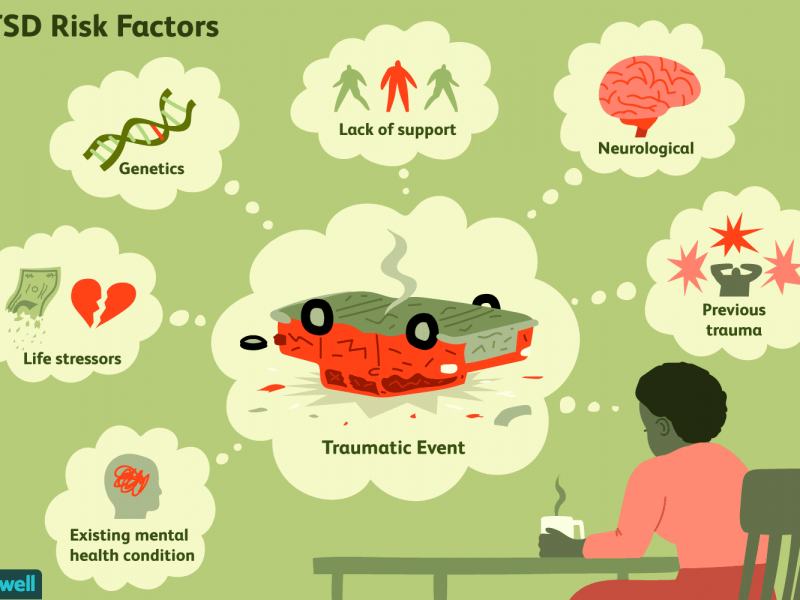

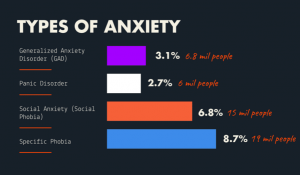

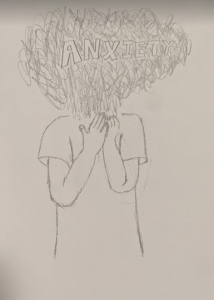

Adaptive behavior is described to be a behavior that allows an individual to cope with PTSD within their environment. It is also used to help with phobias, depression, and anxiety.

Adaptive behavior helps individuals reflect on their ability to meet the demands of everyday life such as:

- relationships

- safety

- eating and drinking

- working

- financial management

- cleaning self and environment

(5)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/ptsd-treatment-2797659_FINAL-5c12be374cedfd00010f866a.png) (4)

(4)

There are many forms of treatments and therapies for PTSD. I have listed some methods of treatment along with short descriptions. These are categorized by treatments that are supported and proved to be effective and treatments that are still being studied for their effectiveness, benefits, and safety

Supported Treatments & Therapies:

Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT): a type of psychotherapy that is effective for both long and short-term results. It focuses on identifying, understanding, and changing thinking and behavioral patterns. The individual has to actively engage inside and outside the appointments. Methods used include:

- exposure therapy

- cognitive restructuring

Presented Centered Therapy (PCT): this is a non-trauma-focused treatment that delves into the current issues of the individual rather than processing the trauma. The counselor discusses psycho-education about the impact of trauma on the individual’s life and teaches problem-solving strategies to deal with current life stressors. (1)

Trauma-Sensitive Yoga: yoga that has gentle movements and less hands-on adjustment. There is an emphasis on choices and freedom to perform the actions and feel their emotions. I can see this being helpful for individuals who have experienced any type of abuse as they did not have control of that element in their life.

Acupuncture: This has been practiced for hundreds of years. Individuals who have experienced acupuncture report feeling less stress and anxiety afterward.

Virtual Reality Exposure: helps the individuals approach the trauma with less fear. They work to become desensitized to the impact of the trauma. The individual will feel a sense of disconnect with the trauma to do the event being played on screens and unable to harm them compared to in person. This allows gradual exposure to the traumatic situation. A patient who was not identified within the article stated: “You go over the story over and over again. I got so bored with my own story that it no longer elicited a reaction.”

Aromatherapy: lavender, chamomile, basil, frankincense for anxiety and PTSD

Nature Exposure: Individuals who sit in nature report feelings of calm, happiness, hope, and aliveness. It has been observed that this experience reduces blood pressure, heart rate, muscle tension, and the production of stress hormones

Music therapy: actively listening to or performing music

Emotional Support Animals

Hypnosis

(4)

Treatments & Therapies being Studied:

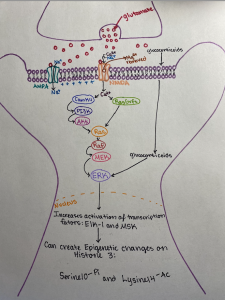

Ketamine infusion: Eskatamine is administered with very low doses to decrease side effects. One infusion treatment for approximately 40 mins can lead to a decrease in PTSD symptoms quickly. The individual will undergo multiple sessions over a few weeks. Esketamine is an NMDA receptor antagonist used to treat adults with treatment-resistant depression. It comes as a nasal spray and can help reduce suicidal and depressive symptoms (2)

MDMA-assisted therapy: The individual will consume ecstasy and work to alter the traumatic memories to become less traumatic as they process the event.

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR): a type of psychotherapy that involves processing trauma-related memories, thoughts, and feelings. The individual will pay attention to either a sound or a back-and-forth movement while thinking about the trauma memory. There are mixed research results to whether the repeated exposure to the trauma or distraction of the sounds and/or eye movements help.

(3) (4)

Resources:

- https://www.ptsd.va.gov/publications/rq_docs/V29N4.pdf

- https://www.webmd.com/anxiety-panic/guide/anxiety-disorders

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2966959/#S1

- https://www.verywellmind.com/ptsd-treatment-2797659

- https://dictionary.apa.org/adaptive-behavior

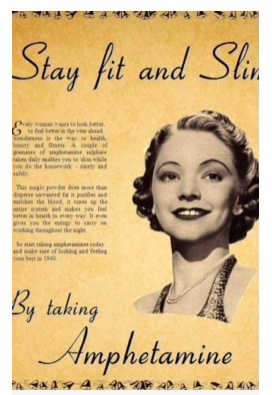

The perfect women would still get all the work done around the house, take care of about 4-6 children, cook food for the whole family (with a dessert – daily), great their husbands nicely dressed and with a smile at the end of the day, then have a long night of sleep. All this, in the midst of the Cold War. Anything seems off? Well, it should, as explained by the perfect recipe of a ‘50s housewife: daily amphetamines and barbiturates.

The perfect women would still get all the work done around the house, take care of about 4-6 children, cook food for the whole family (with a dessert – daily), great their husbands nicely dressed and with a smile at the end of the day, then have a long night of sleep. All this, in the midst of the Cold War. Anything seems off? Well, it should, as explained by the perfect recipe of a ‘50s housewife: daily amphetamines and barbiturates.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/ptsd-treatment-2797659_FINAL-5c12be374cedfd00010f866a.png) (4)

(4)