Hello everyone! Today I’d like to talk a little bit about some factors that influence the development of Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD), specifically how maternal infection/stress can increase the risk of ASD.

ASD is a spectrum of neurodevelopmental disorders that affects 1/58 children in the United States. The key symptoms of ASD, which can range widely in severity, are impaired social interactions, problems with language/communication, and repetitive behaviors.

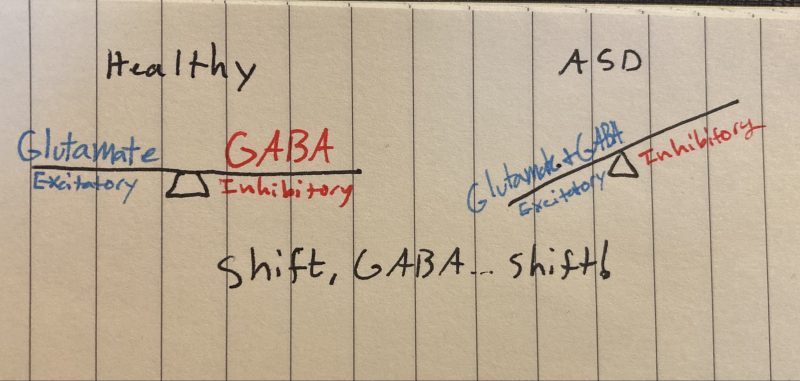

A lifelong condition, the cause of ASD is not yet known, although strides are being made to identify risk factors and molecular mechanisms that cause ASD. Changes in the typical balance between neurons that stimulate other neurons (excitatory: Glutamate) and those that inhibitory other neurons (GABA) represent a key process that may explain ASD.

GLUTAMATE & GABA:

Picture two different neurons—If you’d like you can even color-code them in your head, one green one red. The green neuron produces and uses a neurotransmitter called glutamate to communicate with the other neurons it talks to, while the red neuron uses GABA.

When the green neuron is activated, glutamate is released into the synapse. Glutamate then binds to its receptor on the post-synaptic membrane and ultimately opens up a sodium channel. Positively charged sodium (highly concentrated outside the cell) rushes inside the post-synaptic neuron and makes that neuron more likely to fire, hence glutamate is excitatory. Cool!

Conversely, the red neuron does all the same steps, just swap out glutamate for GABA and chloride for sodium. Just like sodium, chloride is highly concentrated outside the cell and rushes inside once the chloride channel is opened. However, because chloride is negatively charged, increasing intracellular chloride decreases the likelihood of post-synaptic neuronal activation—making GABA inhibitory. The interactions between glutamate and GABA maintain balance in the brain.

At this point, you might be wondering how exactly this relates to ASD etiology. This is the part of the post where I admit that some of what I just told you was wrong. You see, every first-year neuroscience student learns about glutamate and GABA as I just described it, it’s a foundational “ying-and-yang” pillar of neurotransmission. And while it’s true that GABA works like that “most” of the time, GABA works the exact opposite way during brain development.

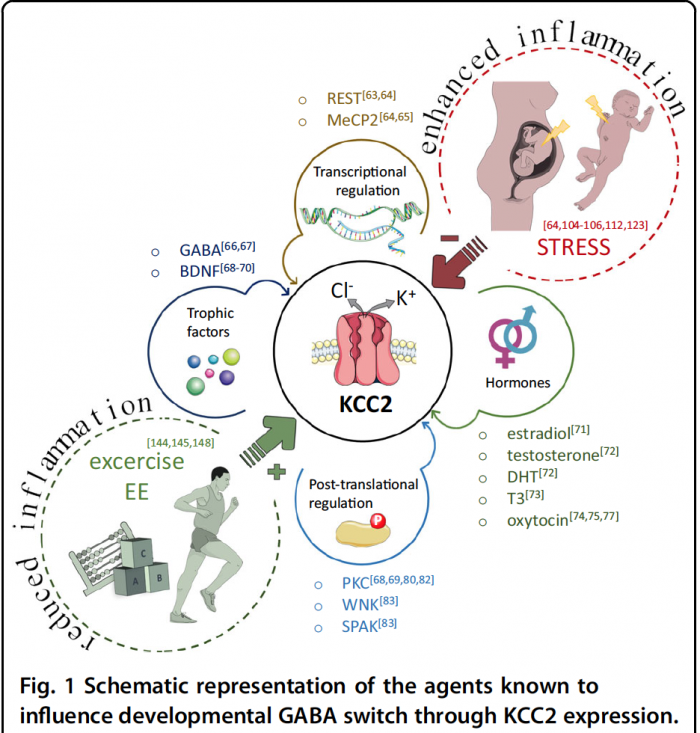

During development, GABA is excitatory—as crazy as that might sound! The brain achieves this by implementing two different chloride ion pumps at different stages of development; an importer and an exporter. During fetal development, the chloride importer (NCKK1) is active and establishes a high intracellular chloride concentration. Once GABA binds and opens its receptor negatively-charged chloride rushes out, causing a net positive effect which makes the neuron more likely to fire—essentially excitatory. This mechanism is critically important during early development, but as fetal development draws to a close an excitatory-inhibitory GABA shift happens. NCKK1 is deactivated and the chloride exporter pump (KCC2) is activated, establishing the typical inhibitory functions of GABA.

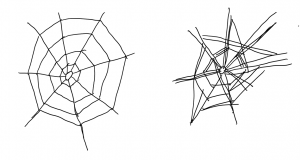

This GABA shift is hypothesized to malfunction/be delayed in the context of ASD. This can cause the brains of individuals with ASD to have too many connections, sensory overload, enlarged cerebrums, and other symptoms of ASD. This begs the question, what dysregulates the chloride ion pumps and causes the malfunctional GABA shift in the first place?

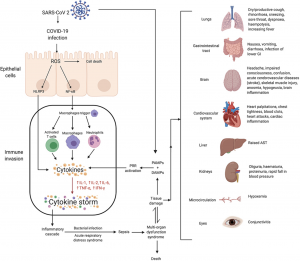

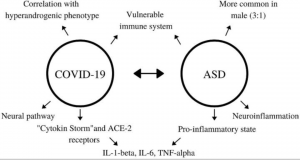

Interestingly, these changes are impacted by changes in the maternal environment during pregnancy. Specific factors (especially prenatal infection and stress) can elevate pro-inflammatory cytokines, one of which (IL-1b) may directly impair the excitatory-inhibitory GABA switch! A rat model of ASD demonstrated that the administration of an NKCC1-blocking drug one day before birth restores many brain functions, especially in the hippocampus, compared to controls. This shows that birth is a critical period for the GABA shift and by proxy ASD development. This same drug decreases ASD symptom severity in humans with few side effects and is a promising avenue of treatment.

The take-home message is that maternal inflammation can cause prenatal neuroinflammation and impair the inhibitory-excitatory GABA shift, which can cause excitatory-inhibitory imbalances throughout postnatal development, increasing the risk of ASD. Understanding how these ion pumps initially go “out of whack” can help researchers design better drugs that more effectively repair the GABA switch with the fewest side effects!

to the infection reaches the fetuses blood circulation supply. Some responses, such as certain antibodies, can be helpful to building the fetus’s immune system, but others, like cytokines, can harm the fetus’s

to the infection reaches the fetuses blood circulation supply. Some responses, such as certain antibodies, can be helpful to building the fetus’s immune system, but others, like cytokines, can harm the fetus’s

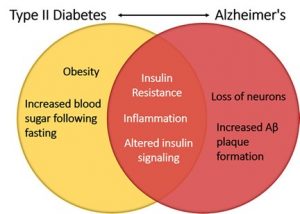

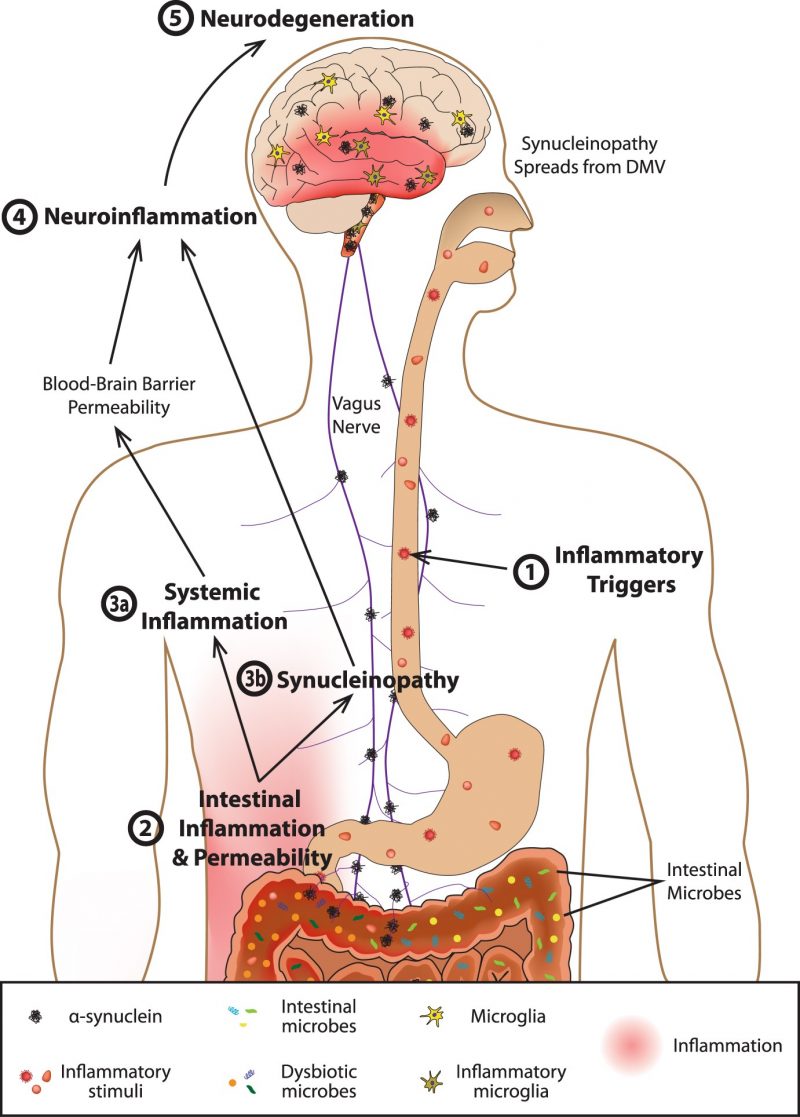

lead to chronic inflammation and ultimately neuron damage and death. The popular term “leaky gut” may play a role in how inflammation even develops within the brain. The gut-blood barrier is very important inside of the body, which prevents things such as undigested food, toxins, and pathogens from crossing over from the GI tract into blood vessels that can then be carried anywhere within the body via the circulatory system.

lead to chronic inflammation and ultimately neuron damage and death. The popular term “leaky gut” may play a role in how inflammation even develops within the brain. The gut-blood barrier is very important inside of the body, which prevents things such as undigested food, toxins, and pathogens from crossing over from the GI tract into blood vessels that can then be carried anywhere within the body via the circulatory system.

The mirror neuron system has a wide variety of functions when working normally. It develops in infants before they have reached 12 months of age and begins to let them understand others’ actions. As the famous Hebbian theory of neuroscience states, “cells that fire together, wire together”. This means that cells that are activated simultaneously form connections. This is also known as associative learning as it results in the brain forming an association between the two objects or concepts (for example, a glass of water and the feeling of thirst). Language development, which is in some ways a form of associative learning, also involved this system.

The mirror neuron system has a wide variety of functions when working normally. It develops in infants before they have reached 12 months of age and begins to let them understand others’ actions. As the famous Hebbian theory of neuroscience states, “cells that fire together, wire together”. This means that cells that are activated simultaneously form connections. This is also known as associative learning as it results in the brain forming an association between the two objects or concepts (for example, a glass of water and the feeling of thirst). Language development, which is in some ways a form of associative learning, also involved this system.

unfortunately still be somewhat difficult to diagnose from a very young age, and so if we as humans have issues diagnosing it within ourselves, it could be even more difficult to actually pin down when observing an animal.

unfortunately still be somewhat difficult to diagnose from a very young age, and so if we as humans have issues diagnosing it within ourselves, it could be even more difficult to actually pin down when observing an animal.  discover similarities in a breed of dog called Bull Terriers, which they found to display some of the (dog equivalent) behaviors that can be diagnosed as autism in humans. I say “dog equivalent” because some of the staple behaviors of ASD are very difficult to distinguish in animals that can’t talk, such as imparied social interaction and not being able to communicate properly, which in humans can manifest as an inability to formulate speech or something similar.

discover similarities in a breed of dog called Bull Terriers, which they found to display some of the (dog equivalent) behaviors that can be diagnosed as autism in humans. I say “dog equivalent” because some of the staple behaviors of ASD are very difficult to distinguish in animals that can’t talk, such as imparied social interaction and not being able to communicate properly, which in humans can manifest as an inability to formulate speech or something similar.  just the behavioral aspect of autism with animals, but also potentially the physiological side of things too.

just the behavioral aspect of autism with animals, but also potentially the physiological side of things too.