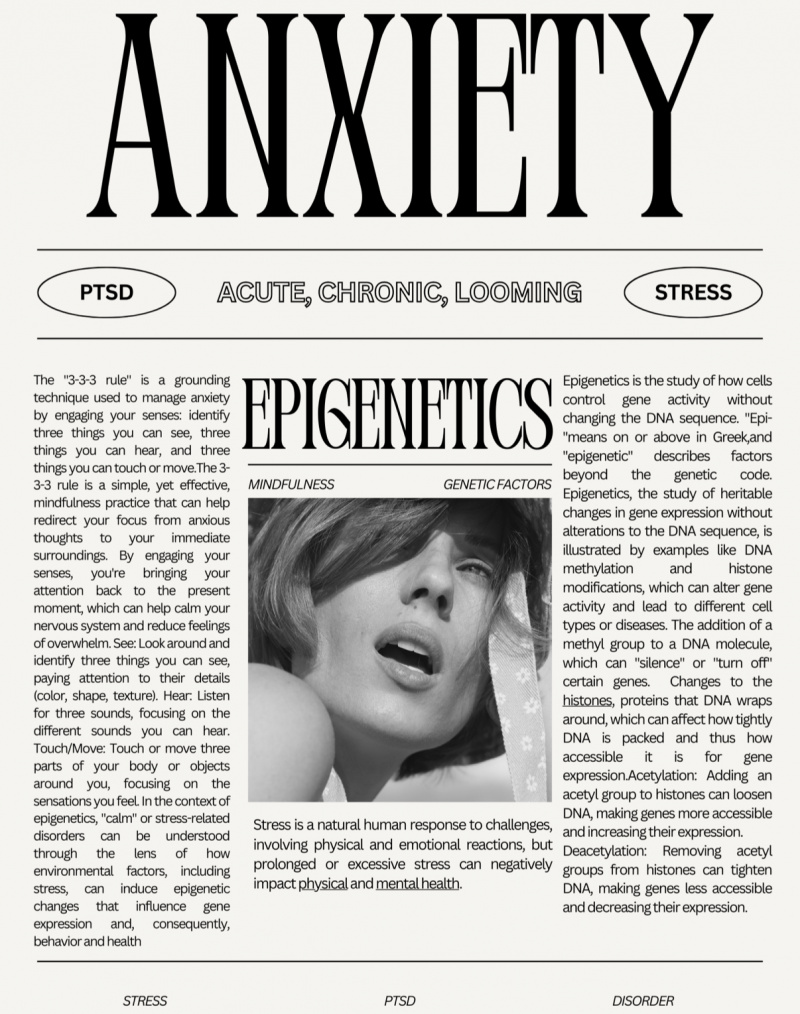

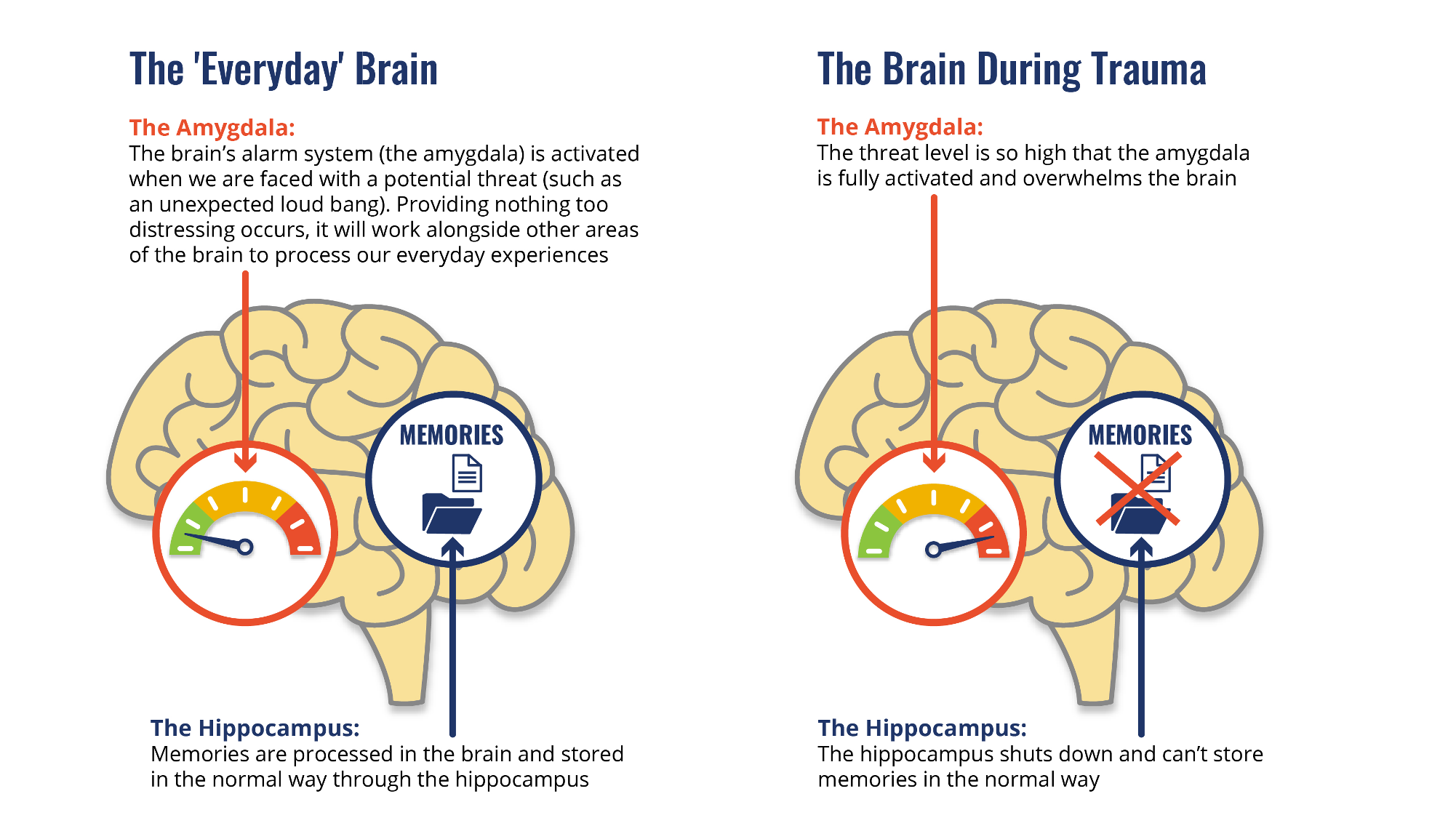

Figure 1: The Addiction Potential of ADHD Medications

Created by Sharleen Mtesa. This image shows the risk of addiction associated with ADHD medications when misused.

Psychostimulants like nicotine, cocaine, and amphetamines—think methamphetamine, MDMA, and even ADHD meds like Adderall are often seen as the bad guys in the world of substance use disorders. And they are, in many ways, wreaking havoc on both physical and mental health. But what’s even more concerning is how these drugs impact the brain’s ability to adapt and rewire itself. When the brain’s natural ability to learn and adjust gets disrupted, recovery becomes that much more challenging.

Therefore, researchers have turned their attention to metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs)—crucial players in learning, memory, and brain plasticity. Emerging evidence suggests that mGluRs play a central role in how the brain rewires itself in response to repeated drug use [1]. And this opens the door to potential therapies that could help us manage, or even prevent, the long-term effects of psychostimulant use disorders (SUDs).

The Highs and Lows of ADHD Meds: How Amphetamines Hack Your Brain

Let’s zoom in on one class of psychostimulants: amphetamines. You’ve probably heard of Adderall and Vyvanse, common medications used to treat ADHD. While they are effective tools for improving focus and attention, they come with a more complex story. Chemically, amphetamines are closely related to street drugs like meth and cocaine, which makes them especially powerful in the way they affect the brain’s reward system.

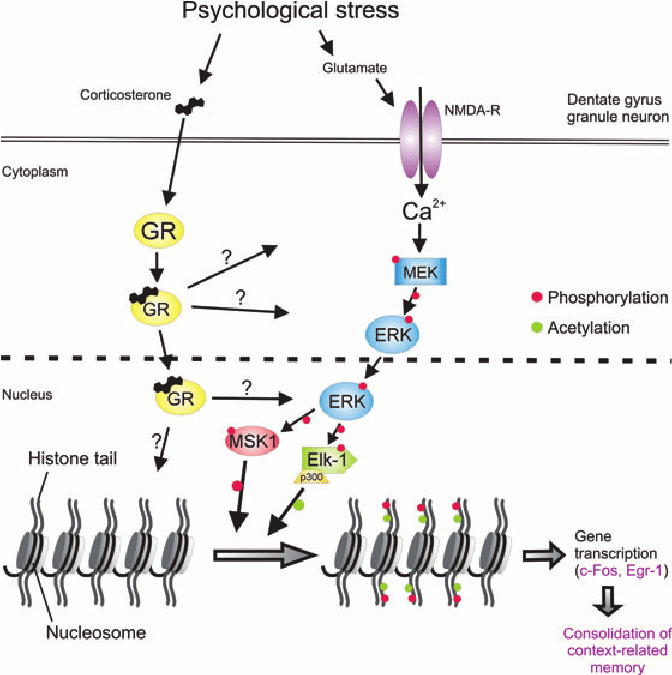

Not only do they boost dopamine and glutamate levels, but they also interact with Group I metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) [2] —specifically mGluR1 and mGluR5. According to the paper “A review on the role of metabotropic glutamate receptors in neuroplasticity following psychostimulant use disorder,” shows that these receptors become more active and start to reorganize in the brain [1]. And the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC)? well this reorganization is especially important in the medial prefrontal cortex, which plays a key role in decision-making and cognitive functions. Changes in the mPFC can affect attention, impulse control, and overall thinking, helping explain why long-term stimulant use impacts these abilities.

So what’s the fallout from all this rewiring? When the mPFC increases its mGluR5 receptor activity, it makes the brain more likely to link the drug with pleasure, long after the first dose. This explains why people who misuse prescription stimulants can develop cravings and get hooked. The addictive potential is real, and understanding these effects is crucial, especially when it comes to medications.

ADHD Medications: Powerful Tools or Potential Pitfalls?

ADHD medications like Adderall, Vyvanse, and Ritalin are often life-changers for people struggling with focus, attention, and impulse control. These medications work by boosting levels of dopamine and norepinephrine [3] in the brain, allowing individuals to stay on task, manage their emotions, and excel in school or at work. For those with ADHD, these medications can be a game-changer, providing the structure and focus they need to thrive. But here’s the twist, when these same medications are misused, whether to stay awake, cram for exams, or chase a euphoric high, they hijack the brain’s reward system.

What Are Adderall and Vyvanse?

Adderall is a combination of two stimulant drugs: amphetamine and dextroamphetamine. By increasing the levels of dopamine and norepinephrine in the brain, Adderall helps improve focus, attention, and impulse control. The immediate-release version typically takes about 30-60 minutes to kick in and lasts around 4-6 hours, while the extended-release (Adderall XR) form provides longer-lasting effects of 10-12 hours.

Vyvanse, on the other hand, contains lisdexamfetamine, which is a prodrug. This means the body must metabolize it into its active form, primarily in the liver. It takes a bit longer to kick in, usually around 1-2 hours, but its effects can last up to 12-14 hours. Because Vyvanse is a prodrug, it has a smoother release, which might make its effects feel less intense compared to Adderall

The Dopamine Pathway: The Power and Pitfalls of ADHD Medications

One of the core reasons why ADHD medications like Adderall and Vyvanse are so effective is because they increase dopamine levels, especially in areas of the brain like the prefrontal cortex and striatum.

How it works:

Dopamine is released into the synapse. Under normal conditions, dopamine is reabsorbed by the neuron through a process called reuptake. But stimulants like Adderall and Ritalin block the dopamine transporter (DAT), preventing dopamine from being reabsorbed. This causes dopamine to accumulate in the synapse, enhancing focus, attention, and motivation.

Key Areas Affected:

- Prefrontal Cortex: This region controls attention, decision-making, and impulse control.

- Striatum: This area is involved in reward, motivation, and habit formation.

The Norepinephrine Pathway: Fueling Focus and Alertness

In addition to dopamine, these medications also boost norepinephrine, another neurotransmitter that’s important for alertness and focus.

How It Works:

Norepinephrine is released from nerve endings and binds to receptors that help increase alertness and focus. Stimulants like Adderall and Vyvanse block the norepinephrine transporter (NET), preventing norepinephrine from being reabsorbed. As a result, norepinephrine stays active in the synapse for longer, helping to maintain focus and attention.

Key Areas Affected:

- Locus Coeruleus: This region regulates arousal, stress response, and alertness.

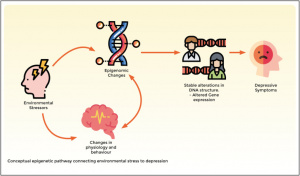

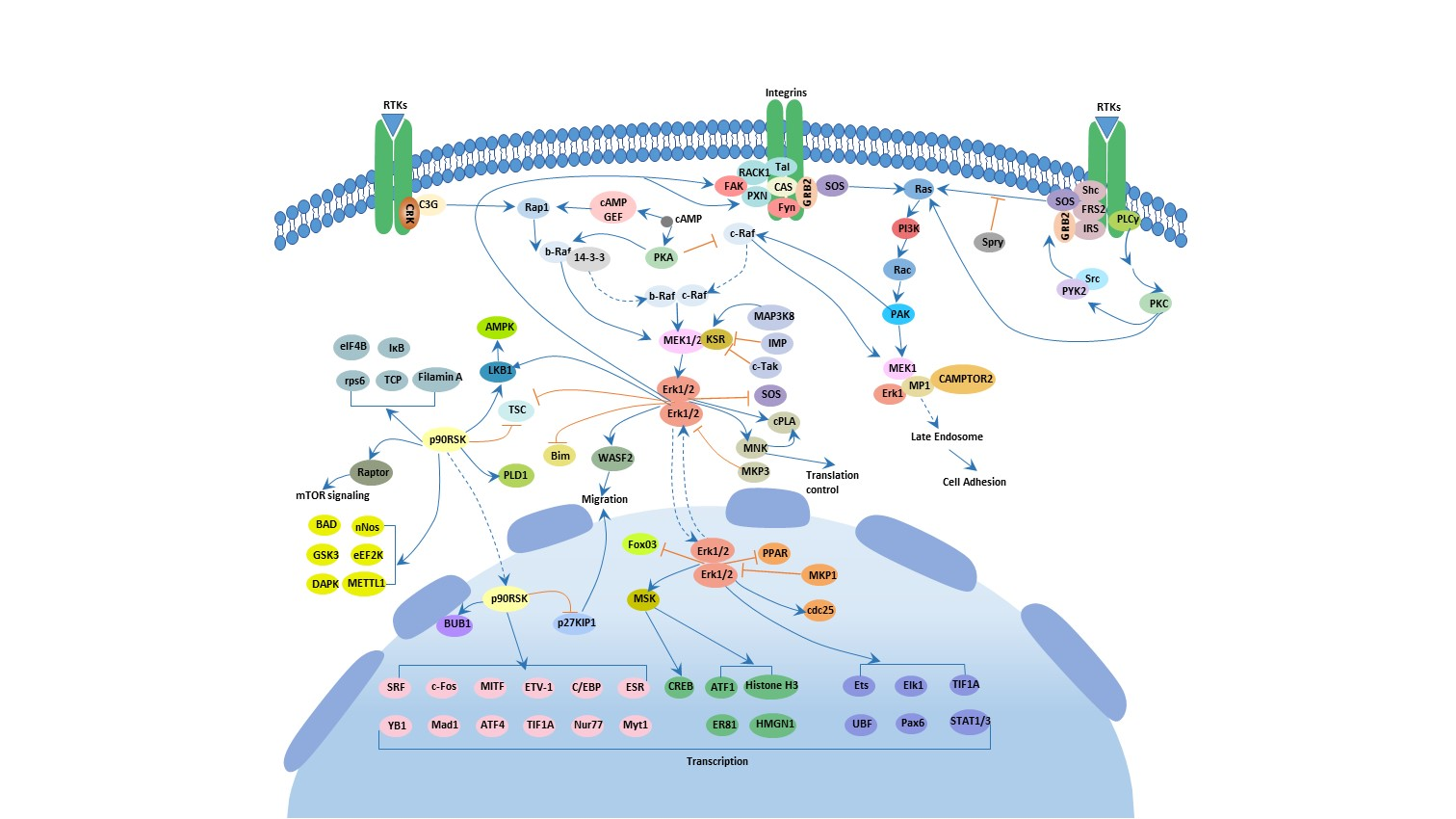

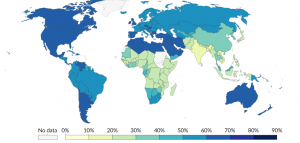

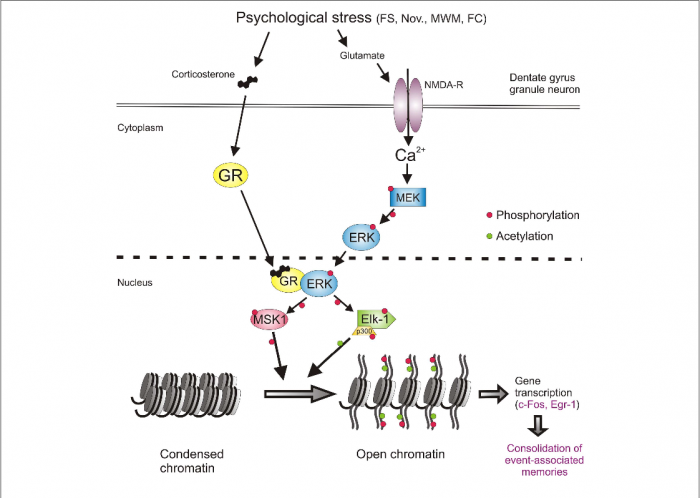

Figure 2: Stimulant Mechanisms of Action in ADHD Medications

This figure shows how ADHD medications like amphetamine (AMPH) and methylphenidate (MPH) increase dopamine (DA) and norepinephrine (NE) levels by affecting the dopamine transporter (DAT) and norepinephrine transporter (NET). AMPH and MPH promote the release of these neurotransmitters through DAT phosphorylation and reverse efflux, inhibiting reuptake and enhancing synaptic activity. [4]

Why This Can Lead to Addiction

While these medications are incredibly helpful for those with ADHD, they can also become addictive if misused. When Adderall or Vyvanse is taken for reasons other than prescribed—like to stay awake longer, study harder, or experience a euphoric high, the mesolimbic dopamine pathway, also known as the reward pathway, becomes activated. This pathway connects the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to the nucleus accumbens, creating powerful feelings of euphoria.

As a result, the brain starts to reinforce this behavior, making the individual crave more of the drug. Over time, this cycle of use and reinforcement increases the risk of addiction.

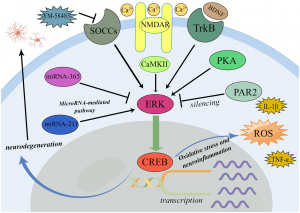

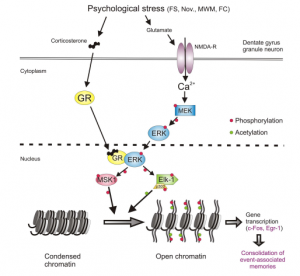

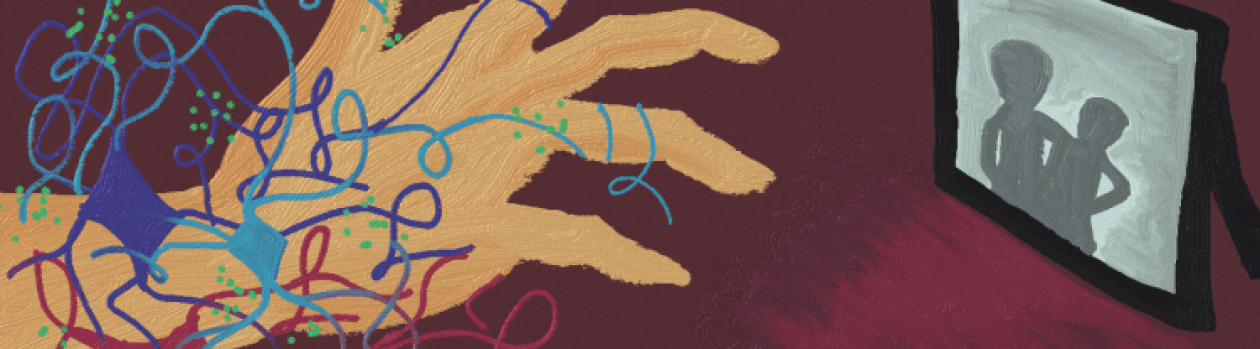

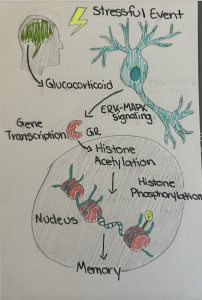

Figure 3: This figure highlights the brain areas impacted by ADHD, including the prefrontal cortex, basal ganglia, limbic system, and reticular activating system. Each area plays a key role in attention, behavior, emotional regulation, and impulse control. In ADHD, deficiencies in dopamine lead to symptoms such as inattention, impulsivity, emotional volatility, and hyperactivity. [5]

The Bitter Aftertaste of a Sweet Fix

So, here’s the bottom line: Adderall and Vyvanse are like superheroes for people with ADHD, helping them focus, stay on track, and crush their goals. But just like every superhero has a dark side, these medications can have unintended consequences when misused. By messing with the brain’s reward system and making it more likely to crave that dopamine rush, they can lead to some serious addiction risks. Understanding how these medications work and how they can rewire the brain will help us strike the right balance between maximizing their benefits and minimizing the risks. After all, the goal is to keep ADHD in check, not to let the medication take control of the brain’s spotlight.

Footnotes:

[1] Mozafari, R., Karimi-Haghighi, S., Fattahi, M., Kalivas, P., & Haghparast, A. (2023). A review on the role of metabotropic glutamate receptors in neuroplasticity following psychostimulant use disorder. Progress in neuro-psychopharmacology & biological psychiatry, 124, 110735. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2023.110735

[2] Niswender, C. M., & Conn, P. J. (2010). Metabotropic glutamate receptors: physiology, pharmacology, and disease. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology, 50, 295–322. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.011008.145533

[3] Del Campo, N., Chamberlain, S. R., Sahakian, B. J., & Robbins, T. W. (2011). The roles of dopamine and noradrenaline in the pathophysiology and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological psychiatry, 69(12), e145–e157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.02.036

[4] Dutta, C. N., Christov-Moore, L., Ombao, H., & Douglas, P. K. (2022). Neuroprotection in late life attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A review of pharmacotherapy and phenotype across the lifespan. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 16. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2022.938501

[5] Jie, T. S. (2021, July 16). ADHD From a Scientific Point-of-View. UnlockingADHD. https://www.unlockingadhd.com/adhd-from-a-scientific-point-of-view/

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/how-to-reduce-stress-5207327_FINAL-907db114a640431ba1e8ecbb9e81b77f.jpg)