Nobody wants to suffer from Alzheimer’s disease, but what is there to do about it but hope it doesn’t happen to you? However, research shows that there are things we can do to delay this disease from impacting us. Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is being called “type 3 diabetes.” Here we will explore why it has been given this name, what is occurring in a brain with AD, and the research on prevention and treatment. [1]

Symptoms of AD

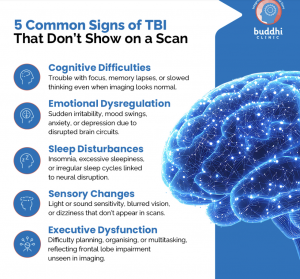

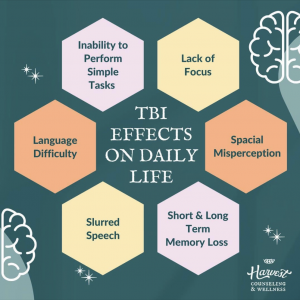

Outwardly, symptoms of AD include difficulties with memory, concentrating, reasoning, thinking, suitable decision making, and planning, as well as changes in personality and behavior. [2]

For more information about how the symptoms of AD present click here

Looking inside the brain

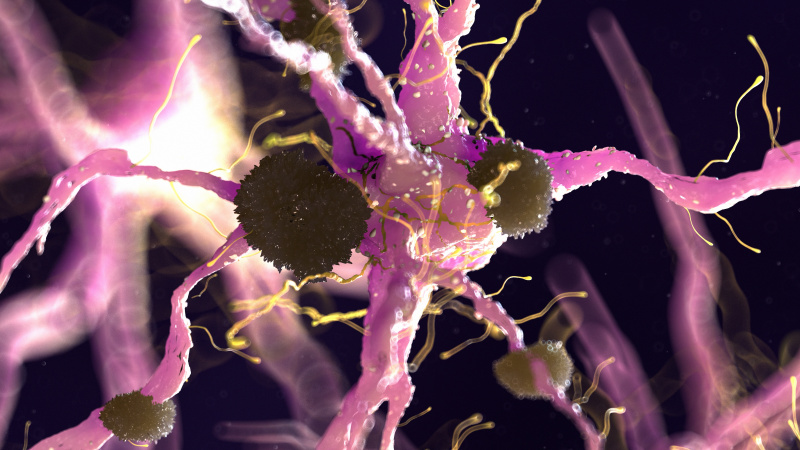

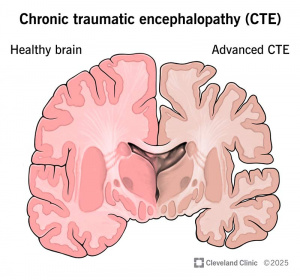

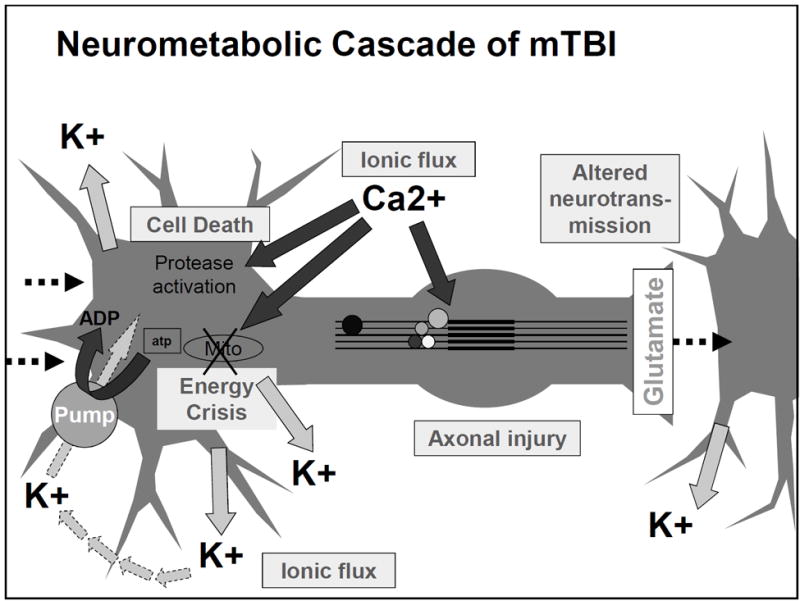

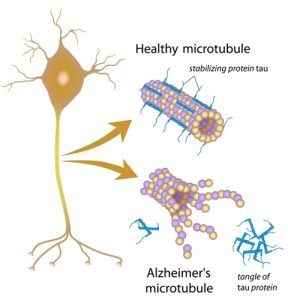

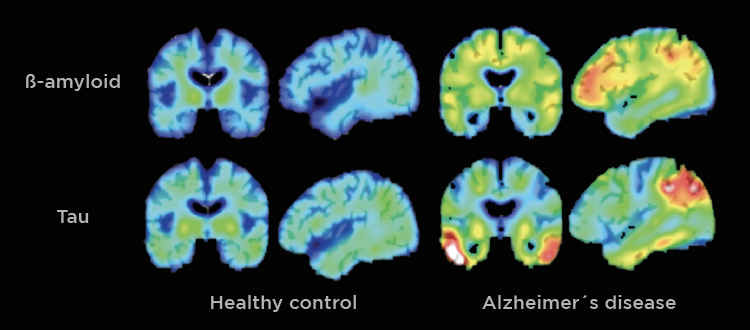

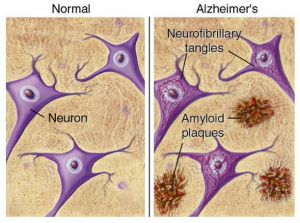

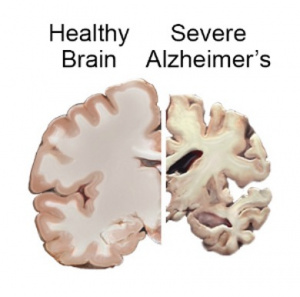

AD is a neurodegenerative disease, meaning neurons and cells in the brain die and brain matter deteriorates. The primary characteristic of AD is neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid-ß plaques. These are basically gunk within and between cells that prevents signals from being able to be sent effectively. It is like when your gutter has leaves clogging it up and blocking water from flowing, but instead of water, brain signals are prevented from continuing to the next cell. Neuroinflammation also plays a large role in AD. [1]

Type 3 Diabetes

Patients with type 2 diabetes are at higher risk for developing AD. Research has shown, that like type 2 diabetes, AD is strongly related to insulin resistance (described below). [1]

Insulin

We most commonly hear about insulin in relation to diabetes. When our blood sugar level is elevated, insulin is responsible for helping cells to absorb this glucose, lowering blood sugar levels. [5] Insulin is important in many other functions as well including cell growth, how the cell uses and produces energy, cell communication, and cognition. [1]

Insulin Resistance

Insulin resistance is a dysfunction of insulin signaling. Insulin does not interact with receptors, causing signaling as often and these receptors are less sensitive to the insulin, so, it takes more insulin for the same effects that took less previously to occur. In AD, this occurs in the brain and leads to neurofibrillary tangles, amyloid-ß plaques, neuroinflammation, and neurodegeneration. [1]

Prevention

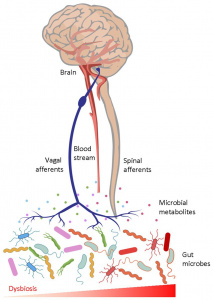

Similar to type 2 diabetes, diet, exercise, and lifestyle play a huge role in the development and progression of AD. Our guts and brains are closely connected through multiple pathways in our body, and limiting fat in diet and eating less processed food can decrease your chances of developing AD as well as many other diseases. [1]

Treatment

Due to its similarities to type 2 diabetes, anti-diabetic drugs are a potential treatment for AD, as well as directly administering insulin to the brain. [1] The potential to dissolve/remove the neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid-ß plaques is also being investigated. There are many aspects and systems involved the progression of AD and it effects a large number of individuals, therefore it continues to be a topic of heavy research for treatment and prevention.

Footnotes

[1] Akhtar, A., & Sah, S. P. (2020). Insulin signaling pathway and related molecules: Role in neurodegeneration and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochemistry International, 135, 104707. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuint.2020.104707

[2] Alzheimer’s disease—Symptoms and causes. (n.d.). Mayo Clinic. Retrieved February 14, 2026, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/alzheimers-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20350447

[3] Armstrong, B. (2025, February 24). Understanding Plaques and Tangles in Alzheimer’s Disease. Kinesiology. https://kin.uncg.edu/2025/02/24/plaques-and-tangles/

[4] Alzheimer’s Disease Fact Sheet. (2023, April 5). National Institute on Aging. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/alzheimers-and-dementia/alzheimers-disease-fact-sheet

[5] Lannon, R. (2024). How Stress Hormones Affect Blood Sugar Levels in Diabetes. African Journal of Diabetes Medicine, 32(5). https://doi.org/10.54931/AJDM-32.5.7

[6] Tan, H.-E. (2023). The microbiota-gut-brain axis in stress and depression. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 17. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2023.1151478