Most athletes who play any contact sport at whatever level can relate to the guilt of injury, the feeling of not being there for your brothers and sister to fight for that W, bring that trophy home to a bunch of rabid fans, satisfy your own insatiable competitive will, prove the haters wrong, I get it, I’ve felt that too. To parents who’s offspring have dealt with a sports related injury, perhaps you are worried sick and want them to recover like yesterday so your kid can get off the couch, make some friends, learn to be tenacious, gracious in the face of defeat, disciplined even when it is physically painful, all of which are admirable traits that sport teaches us. To the service member who got concussion while out there training and fighting to ward off enemies both home and abroad, is eager to prove his worth to his fellow troops, eager not to let his family down, eager to please his commander, give me an ear. Today, I write to plead with you all: Concussed? Sit it out pal, you’ll thank me later! A concussion is defined as a clinical syndrome characterized by immediate and transient alteration in brain function, including alteration of mental status and level of consciousness, resulting from mechanical force or trauma. Here is what follows physiologically.

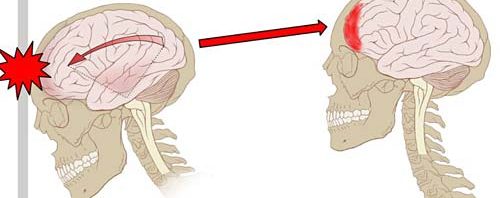

A concussed individual may develop cerebral edema, accounting for loss of consciousness, memory impairment, disorientation and headache. The Brain’s auto regulatory mechanisms compensate for this mechanical and physiologic stress and protect against massive swelling by acutely limiting cerebral blood flow, which leads to accumulation of lactate and intracellular acidosis. A state of altered cerebral metabolism occurs and may last ten days, involving decreased protein synthesis and reduced oxidative capacity. Loss of consciousness after head injuries, the development of secondary brain damage, and the enhanced vulnerability of the brain after an initial insult can be explained largely by characteristic ionic fluxes, acute metabolic changes, and cerebral blood flow alterations that occur immediately after cerebral concussions. Extracellular potassium concentration can increase massively in the brain after concussion, followed by hypermetabolism lasting up to ten days. This makes the brain more vulnerable and susceptible to death after a second sub-lethal insult of even less intensity.

Second Impact Syndrome (SIS), first described by Richard L. Saunders, MD and Robert E. Harbaugh, MD in 1984, consists of two events. Typically, it involves a patient suffering post-concussive symptoms following a head injury. If the patient sustains a second head injury/concussion, diffuse cerebral swelling, brain herniation, and death can occur. Though it is rare, it is devastating in that young, healthy patients may die within a few minutes. Fisher J, and Vaca F, hence conclude that when the patient sustains a “second impact,” the brain loses its ability to auto regulate intracranial and cerebral perfusion pressures. In severe cases, this may lead to cerebral edema followed by brain herniation. In a few implicated cases, death has been reported to occur in a matter of two to five minutes, usually without time to stabilize or transport an athlete from the playing field to the ED. This demise can occur far more rapidly than that of an epidural hematoma. Recent research has pointed out that brain swelling in minor head trauma is more significant in small children than in adults. The term “malignant brain edema” has been used to describe this phenomenon. Though more research in this area is necessary to determine if and when malignant brain edema and SIS are related, or even if they occur by the same process, it is unquestionable that getting back on the field of play or re-engaging in contact activity before a concussion is fully healed makes one more vulnerable to sustaining a second concussion. So again I say and again I plead, sit it out pal, you’ll thank me later!

Concussed? Sit It Out Pal, You’ll Thank Me Later!