Susan Greenhalgh’s 2015 book Fat Talk Nation: The Human Costs of America’s War on Fat, identifies the idea that “Weight is under individual control; virtually everyone can lose weight and keep it off through diet and exercise. Weight-loss treatments work; if they don’t, it’s due to lack of willpower on the part of the dieter,” as a key myth implicitly linking moral failure to obesity and underlying the burgeoning social, political, and economic effort to fight growing obesity rates in American citizens (30). Greenhalgh argues that this myth perpetuates and underpins many of the negative psychological and social consequences that people of a non-standard body size endure (31). Globally, 1.9 billion adults are overweight and, of these, 650 million were obese according to 2016 data from the World Health Organization. Therefore, the question of how and why obesity is linked to moral failure is highly relevant and has real consequences for many people. In fact, a 2012 study from the University of Minnesota found that 50% of people identifying as female and 38% of people identifying as male engage in unhealthy weight control behaviors. These harmful behaviors include things like skipping meals, fasting, smoking cigarettes, binge eating & purging, using laxatives or diuretics, and taking diet pills. Clearly, the link between obesity and moral failure has real, non-trivial consequences for individuals seeking a lower body size.

However, some key factors impacting your weight really aren’t subject to your conscious decision-making processes. Nothing in obesity makes sense except in light of dysregulated hormone balance. Let’s dive into the neuroscience behind hunger and obesity to explore how hormone balance in the hypothalamus regulates feelings of hunger and satiety.

Inside the Brain.

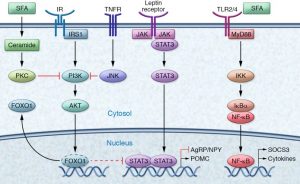

Ghrelin, Leptin, and Insulin are three key hormones that create the balance between hunger and satiety that tell your body when you need to eat, and when you’re feeling full. It’s complicated, so let’s use a graphic to break it down.

Fig 1: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5199695/

Ghrelin (not pictured on the graphic) signals to the brain that there is not enough available energy in the body and increases food intake by creating the feeling of hunger in the hypothalamus. Since Ghrelin and Leptin have opposite effects, it’s logical that they work through different mechanisms as well. Leptin (Fig 1: purple receptor, middle top of graphic) works in the opposite fashion by telling the brain that you have enough energy stored, creating feelings of satiety via a JAK-STAT signaling cascade. Insulin, like leptin, responds to energy stores but works in a slightly different way. Insulin will actually interact directly with the Leptin pathway via a protein signaling cascade that results in FOXO1 inhibition of STAT3, leading to satiety (Figure 1).

So how does this relate to the myth of control and the link between moral failure and obesity?

The balance between Leptin, Ghrelin, and Insulin is actually quite precarious. Any change in the relative levels of these hormones can lead to decreased feelings of satiety, increased eating, and obesity or, conversely, to increased feelings of satiety, decreased eating behavior, and symptoms of anorexia. Specifically, increased inflammation in the hypothalamus can lead to decreased leptin & insulin signaling, leading to increased eating and, potentially, obesity. So, clearly, every factor that forms an individual’s weight is not under their explicit, conscious control.

Conclusion

The vast majority of messages people receive surrounding weight and body size either explicitly or implicitly punish fat people. Greenhalgh identifies both critical (“if you don’t stop eating, you’ll look like that fat person”) and, often well-intentioned, complimentary examples (“Wow, you’ve lost weight; you look fantastic”) of what she calls “Biopedagogical fat-talk” as unnecessary and harmful to people’s self-conception and body image (35). Therefore, be kind to others and yourself, and remove comments about body size and appearance from your dialogues. Instead, seek a deeper connection in your conversations and move the focus away from appearances.