We all experience stress. And we all remember those moments when life seemed overwhelming—finals week, heartbreak, a fender bender, or worse. These memories shape how we see the world and how we respond to future challenges. But have you ever wondered why some stressful experiences stay with us for years, while others fade quickly? Or why some people develop anxiety disorders or PTSD after trauma, while others don’t? Therefore, it’s essential that we understand not just that we remember stress—but how our brain encodes it, right down to the molecular level.

The Science of Stressful Memories: A Look Inside the Brain

In the article Making Memories of Stressful Events by Dr. Johannes Reul, a remarkable discovery is unpacked: when we undergo psychological stress, our brain physically changes to record that experience—starting with our DNA.

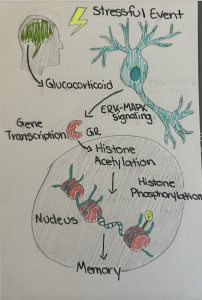

Here’s how it works: stress triggers the release of glucocorticoid hormones (like cortisol), which bind to glucocorticoid receptors (GRs) in the brain—especially in the hippocampus, the region responsible for memory. At the same time, glutamate activates NMDA receptors, kicking off a signaling cascade called the ERK-MAPK pathway. [1]

The magic happens when these two systems converge, forming a biological memory-making machine. This convergence leads to changes in the structure of histones, the proteins that package DNA. Specifically, a dual histone mark (H3S10 phosphorylation and K14 acetylation) appears, unlocking genes like c-Fos and Egr-1 which are crucial for memory consolidation. [1]

Figure 1 [2] Artstract by Ella Alsleben. Stressful experiences trigger glucocorticoid release and ERK-MAPK signaling in the brain, leading to epigenetic modifications like histone acetylation and phosphorylation in neurons. These molecular changes promote gene transcription that consolidates the memory of the event.

Why Should You Care

This research explains why some people develop disorders like PTSD after trauma—and others don’t. Only about 10–20% of people develop lasting mental health issues after a major stressor. This suggests that the way our brains process stress at the molecular level plays a major role in our mental resilience. [3]

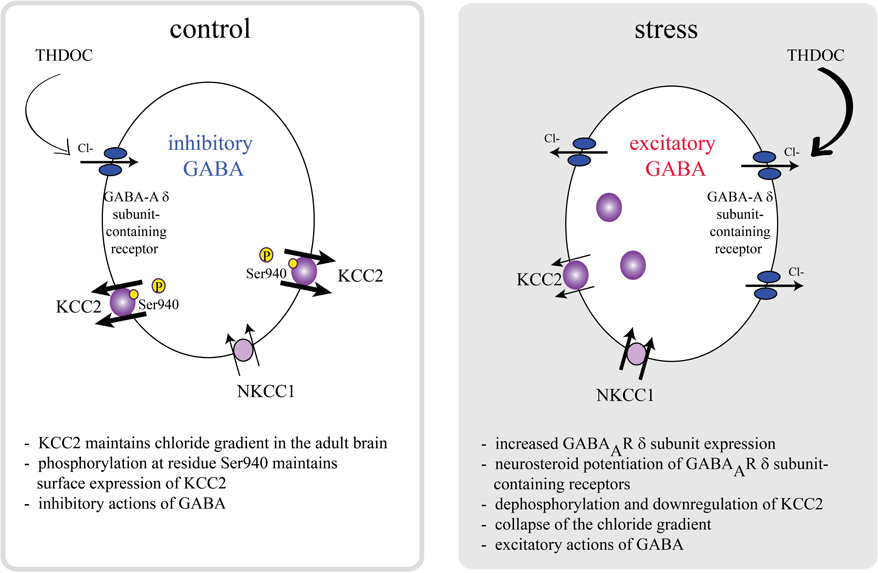

Figure 1 [4]: Showing the difference between GABA in a normal functioning adult under non-stressful conditions and one under stressful conditions.

The study also revealed that GABA, the brain’s calming neurotransmitter, modulates this memory-encoding process (see Figure 1). More anxious individuals have lower GABAergic tone, which means their brains are more reactive to stress, forming stronger stress memories. Conversely, exercise was shown to increase GABA and reduce the brain’s stress response. [1]

So if you’ve ever wondered whether daily exercise can really help manage anxiety—the answer is, yes, even at the level of your DNA.

What Should You Take Away From This

This isn’t just a neuroscience geek-out—it’s a story about how our bodies remember, and how we can influence those memories.

If you’re a student, knowing that high anxiety makes stressful moments “stick” more might encourage you to seek out mental wellness tools before finals week (Figure 2).

If you’re managing anxiety, exercise isn’t just about physical health—it’s an epigenetic intervention.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/how-to-reduce-stress-5207327_FINAL-907db114a640431ba1e8ecbb9e81b77f.jpg)

Figure 2 [5]: Wellness tools that can help relieve stress.

And if you’re someone who’s endured trauma, this science brings hope. Understanding the pathways that encode stress memories means we are one step closer to therapies that can help “unwrite” them.

Let’s Reframe the Conversation

Instead of viewing stress as something abstract or purely emotional, we can now see it as a physical imprint (Figure 3), a story our neurons etch into our DNA. And that story is shaped by biology, yes—but also by environment, habits, and resilience.

Understanding this empowers us to care for our mental health not just with willpower, but with scientific insight.

So the next time someone tells you that stress is “all in your head”—you can smile and say, “Yes, and it’s in my chromatin too.”

Figure 3 [5]: Each story shapes our biology into the person we are today.

References

[1] Reul J. M. (2014). Making memories of stressful events: a journey along epigenetic, gene transcription, and signaling pathways. Frontiers in psychiatry, 5, 5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00005

[2] Artstract by Ella Alsleben

[3] Schneiderman, N., Ironson, G., & Siegel, S. D. (2005). Stress and health: psychological, behavioral, and biological determinants. Annual review of clinical psychology, 1, 607–628. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.144141

[4] Mody, I., & Maguire, J. (2012). The reciprocal regulation of stress hormones and Gabaa receptors. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2012.00004

[5] Rebecca Valdez, M. (2024, June 10). Techniques to reduce stress and anxiety. Verywell Health. https://www.verywellhealth.com/how-to-reduce-stress-5207327

[6] Brain+puzzles images – browse 163,431 stock photos, vectors, and video. Adobe Stock. (n.d.). https://stock.adobe.com/search?k=brain%2Bpuzzles