Imagine a child taking a hard fall off a bike or a teenager colliding with another player on the football field. They might feel dizzy, sit out for a bit, and then seem fine. But inside their brain, a hidden chain reaction may have started that could affect how they think, feel, and learn for years to come. Therefore, understanding traumatic brain injury (TBI) and concussion, especially in children, is not just a medical issue, but a public health issue that affects families, schools, and society as a whole.

The Science: What Happens in the Brain After a Concussion or TBI

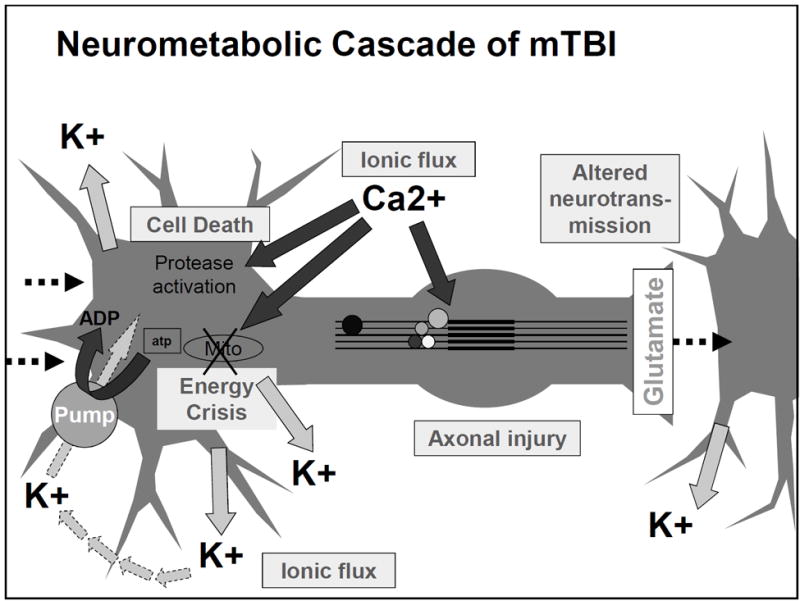

Concussion triggers a complex chain of chemical and metabolic events in the brain. Immediately after impact, neurons release large amounts of glutamate, an excitatory neurotransmitter. This overstimulation causes an ionic imbalance, with potassium leaving cells and calcium flooding in. To restore balance, neurons use large amounts of ATP which leads to a metabolic crisis because blood flow and glucose delivery can’t keep up. Figure 1 shows this cascade of events. This mismatch between energy demand and supply makes brain cells vulnerable to more damage and explains why repeated concussions are so dangerous [1]. To learn more about this process more in depth, click here.

Why This is Even More Important in Children and Adolescents

While concussions are serious for adults, they are uniquely dangerous for children because their brains are still developing. TBI is the leading cause of disability and death in children ages 0-4 and adolescents 15-19, and around 145,000 children and adolescents live with long lasting cognitive, physical, or behavioral impairments after a TBI. Children experience 1.1-1.9 million sports and recreation related concussions every year in the United States, making this a widespread issue [3].

During childhood, the brain is undergoing synaptic pruning, myelination, programmed cell death, neurotransmitter regulation, and white/gray matter differentiation [2]. These process shape learning, memory, and behavior. A brain injury during these critical periods can permanently alter how neural circuits are built, which may affect cognition and mental health long-term.

Children are also biologically more vulnerable to brain injury because their brains are still developing and not yet balanced. In the brain, there are excitatory signals that make neurons more active and inhibitory signals that calm neurons down. In children, the excitatory systems mature earlier than the inhibitory systems, meaning their brains are naturally more “turned up” and less able to control too much activity. After concussion, large amounts of glutamate are released, which overstimulates brain cells. Because children’s brains are already more excitable, this overstimulation can become more intense and damaging. Pediatric brain injuries also involve higher activity of NMDA receptors (which amplify excitatory signals) and delayed development of GABA signaling (which normally calms the brain). This imbalance makes children more likely to experience seizures or even epilepsy after a TBI [4].

Long Term Impacts: More Than Just a Headache and What This Means for the Public

Effects of childhood TBI are not limited to the immediate injury. Long term outcomes can include:

- Behavioral effects: anxiety, depression, mood swings, ADHD-like symptoms, and autism-like behaviors

- Cognitive effects: memory problems, attention deficits, difficulty with problem-solving, and increased risk of neurodegenerative diseases later in life

- Physical effects: headaches, dizziness, fatigue, and sensory disturbances [5]

Children also take longer to recover from concussions than adults, often around 4 weeks or more, due to ongoing myelination and vulnerability of developing axons. Therefore, the public should care because concussions are not just temporary injuries, they can reshape a child’s brain during critical developmental windows. Understanding the neurometabolic cascade helps explain why rest, gradual return to activity, and modern “active recovery” approaches are so important [6].

Parents, educators, and coaches should recognize that preventing and properly treating childhood TBI is an investment in lifelong cognitive and mental health. Increased awareness, better helmet and sports safety policies, and early intervention can significantly reduce long-term issues from TBIs.

References

[1] C. C. Giza and D. A. Hovda, “The New Neurometabolic Cascade of Concussion,” Neurosurgery, vol. 75, no. 4, pp. S24–S33, Oct. 2014, doi: https://doi.org/10.1227/neu.0000000000000505.

[2] K. N. Parker, M. H. Donovan, K. Smith, and L. J. Noble-Haeusslein, “Traumatic Injury to the Developing Brain: Emerging Relationship to Early Life Stress,” Frontiers in Neurology, vol. 12, Aug. 2021, doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2021.708800.

[3] “Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injury,” Asha.org, 2016. https://www.asha.org/practice-portal/clinical-topics/pediatric-traumatic-brain-injury/?srsltid=AfmBOorKNcIjIYe7nnJHIYbXQxlVKQBlzOrqvx7t_IJmC5hWi-v39zwR#collapse_4

[4] S. Agrawal et al., “Paediatric traumatic brain injury: unique population and unique challenges,” Brain, Dec. 2025, doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awaf459.

[5] “Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) in Children,” Luriechildrens.org, 2024. https://www.luriechildrens.org/en/specialties-conditions/traumatic-brain-injury/

[6] B. Johnson, “Kids experience concussion symptoms 3 times longer than adults – Find a DO | Doctors of Osteopathic Medicine,” Find a DO | Doctors of Osteopathic Medicine, Oct. 2018. https://findado.osteopathic.org/kids-experience-concussion-symptoms-3-times-longer-than-adults (accessed Feb. 10, 2026).