[1]

A concussion, a form of mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), occurs when biomechanical force is applied to the brain and produces functional disturbances without obvious structural damage on standard imaging. These disturbances can generate symptoms such as headaches, dizziness, nausea, photophobia, and slowed cognitive processing. Because concussions frequently occur in athletic participation and military service, understanding their biological impact extends beyond the clinic and into everyday decision-making.

For readers seeking a foundational overview of concussion mechanisms and symptoms, concussion overview resources can provide helpful context.

Despite advances in research, uncertainty remains regarding what full recovery truly means. Observable symptoms may resolve within days, yet metabolic and cellular processes may continue beneath the surface. This neurometabolic complexity challenges symptom-based recovery assessment and raises concerns about when individuals should safely resume high-risk activities. Biomarker research, including studies of N-acetylaspartate (NAA), whose levels decrease following injury and gradually normalize during recovery, suggests that biological healing may lag behind symptom resolution.[2]

Therefore, examining concussion through a molecular lens reframes recovery as an ongoing physiological process rather than a purely symptomatic experience. A brief visual explanation of symptom progression versus biological recovery can be explored in this short educational video.

Inside the brain’s emergency response

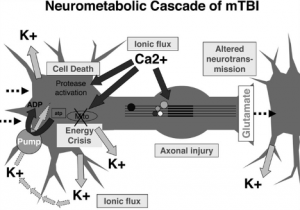

The article by Giza and Hovda describes concussion as triggering a neurometabolic cascade characterized by ionic flux, excessive glutamate release, and increased energy demand.[2] Immediately following injury, potassium exits neurons while calcium enters, disrupting cellular equilibrium. Excessive glutamate release amplifies neuronal activation, forcing cells to expend ATP to restore balance. This mismatch between energy supply and demand creates a temporary metabolic crisis associated with slowed cognition and impaired reaction time.

Mitochondrial strain and altered neurotransmission may persist even in the absence of widespread neuronal death. Spectroscopy studies reporting reduced NAA levels further support the idea that neuronal metabolic function may recover more slowly than symptoms resolve.[2] These findings reinforce that a concussion is not merely a mechanical event, but a dynamic biochemical process unfolding over time.

Figure 1: Neurometabolic cascade following concussion[2]

Figure 1: Neurometabolic cascade following concussion[2]

Why the science matters beyond the Lab

Understanding these mechanisms informs both prevention and recovery strategies. Efforts aimed at reducing concussion incidence increasingly emphasize behavioral adjustments and protective practices, as discussed in concussion prevention in sports.

Recognizing that biological healing may extend beyond symptom relief also helps contextualize why some individuals experience lingering cognitive effects, a phenomenon explored in discussions of post-concussion recovery variability.

At a broader societal level, awareness of cumulative neurological risks has reshaped conversations surrounding athlete safety and military health. Conditions such as chronic traumatic encephalopathy are described in clinical overviews of CTE, reinforcing the importance of long-term monitoring and informed policy decisions.

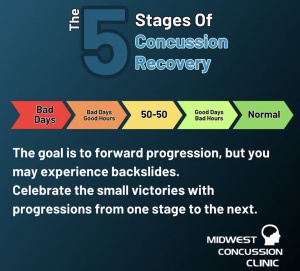

Figure 2(right): Illustration of the nonlinear nature of concussion recovery, showing that progress may fluctuate and reinforcing the importance of considering biological healing beyond symptom resolution.[3]

Figure 2(right): Illustration of the nonlinear nature of concussion recovery, showing that progress may fluctuate and reinforcing the importance of considering biological healing beyond symptom resolution.[3]

Moving forward

Exploring concussion through molecular neuroscience reinforces that recovery is more than the absence of symptoms; it is a biological process unfolding at the cellular level. Recognizing this complexity invites continued curiosity about emerging biomarkers and recovery assessment tools. Ultimately, understanding the hidden physiology of concussion empowers individuals and communities to approach brain health with greater caution, awareness, and scientific engagement.

Bibliography

[1] asc-ca, “What is a Concussion?,” Ace Sports Clinic. Accessed: Feb. 10, 2026. [Online]. Available: https://www.acesportsclinic.com.au/blog/what-is-a-concussion/

[2] C. C. Giza and D. A. Hovda, “The new neurometabolic cascade of concussion,” Neurosurgery, vol. 75 Suppl 4, no. 0 4, pp. S24-33, Oct. 2014, doi: 10.1227/NEU.0000000000000505.

[3] “Midwest Concussion Clinic – Matt Campbell on Instagram: ‘The 5 Stages of Concussion Recovery is something we discuss with our patients. It’s a way to provide visual representation as to progress in your recovery. The goal is to always move forwards between stages, but sometimes we have setbacks. Setbacks do not mean that you’re “getting worse.” They simply represent a temporary increase in symptoms. Have you ever been educated on the stages of recovery? #Concussion #ConcussionRehab #ConcussionEducation #ConcussionAwareness #ConcussionClinic #ConcussionRecovery #MWConcussion,’” Instagram. Accessed: Feb. 11, 2026. [Online]. Available: https://www.instagram.com/mwconcussion/p/CvYbaU9Aiwb/