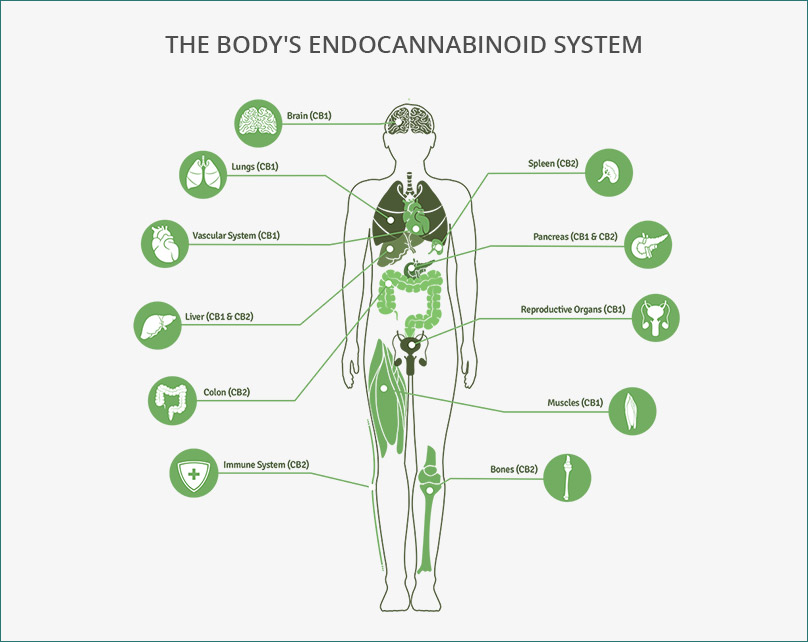

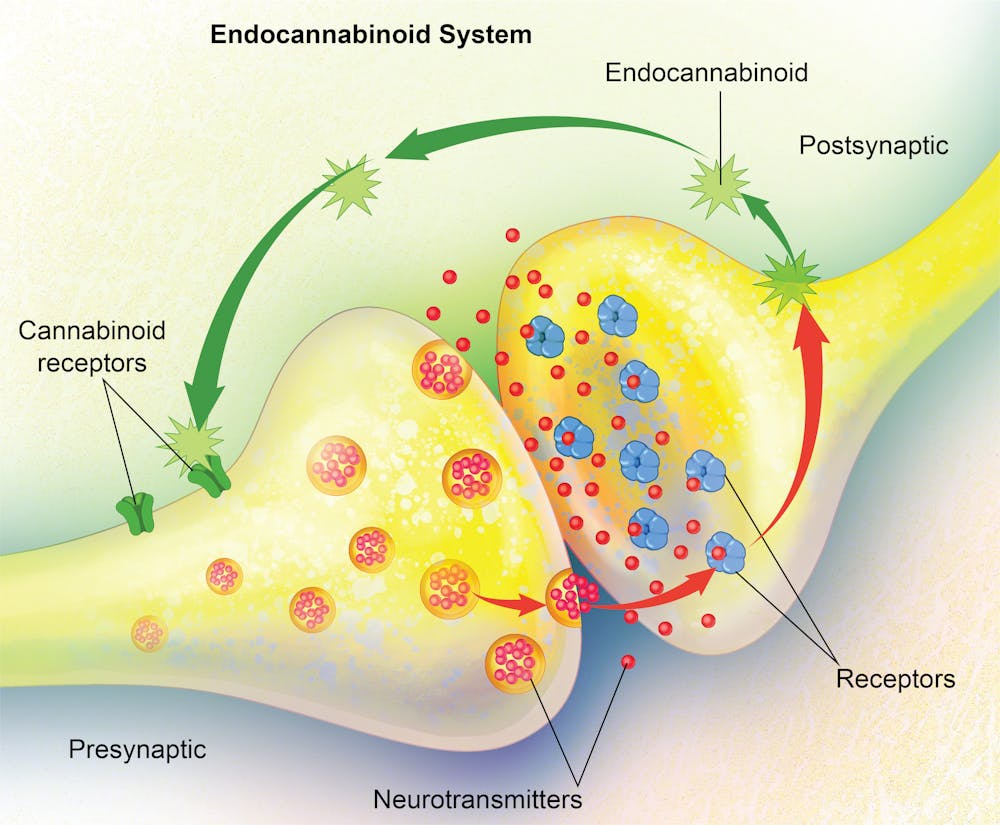

The human body is a finely tuned machine, constantly regulating pain, mood, metabolism, and more to maintain balance. One important system responsible for this regulation is the endocannabinoid system (ECS), a network of cannabinoid receptors(CB1 and CB2) , endocannabinoids (Anandamide (AEA) and 2-Arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) ) , and enzymes (FAAH and MAGL) that work together to keep everything running smoothly. This means that the ECS helps regulate things like pain perception, mood, immune function, and metabolism. It’s constantly monitoring the body’s needs and adjusting accordingly, ensuring that everything stays in balance. [1]

- Endocannabinoids (AEA and 2-AG) are produced when needed and act locally to help regulate these functions.

- Cannabinoid Receptors (CB1 and CB2) are activated by these endocannabinoids to trigger specific responses.

- Enzymes (FAAH and MAGL) break down these molecules once they’ve done their job, ensuring the ECS doesn’t overdo it.

But maintaining balance isn’t as simple as turning functions on and off. If the ECS activated all its pathways randomly or continuously, it could lead to dysfunction instead of stability. That’s why it relies on selective signaling, only activating specific pathways when needed to ensure precise control.

Therefore, understanding how the ECS’s selective signaling works is essential for improving health. By learning how to support this system, we can regulate vital functions more effectively while avoiding unwanted side effects, helping the body stay in perfect balance.

So, how does the ECS know when and where to act? It carefully monitors the body’s needs and responds accordingly. Without selective signaling, ECS pathways would activate constantly and unpredictably, disrupting balance rather than maintaining it.

What Is Selective Signaling and Why Does It Matter?

Selective signaling is the ability of the ECS to target specific pathways or receptors at just the right time and place [2]. It’s like a light switch, when you need light in a room, you flip the switch, and it turns on just the right amount. If the light was on everywhere, all at once, it would be too bright and overwhelming.

The ECS uses selective signaling to activate only the receptors that are needed in specific tissues, reducing unnecessary effects elsewhere. This process is achieved through factors such as GPCR signalling and β-Arrestin Pathway.

The GPCR Pathway in the Endocannabinoid System (ECS)

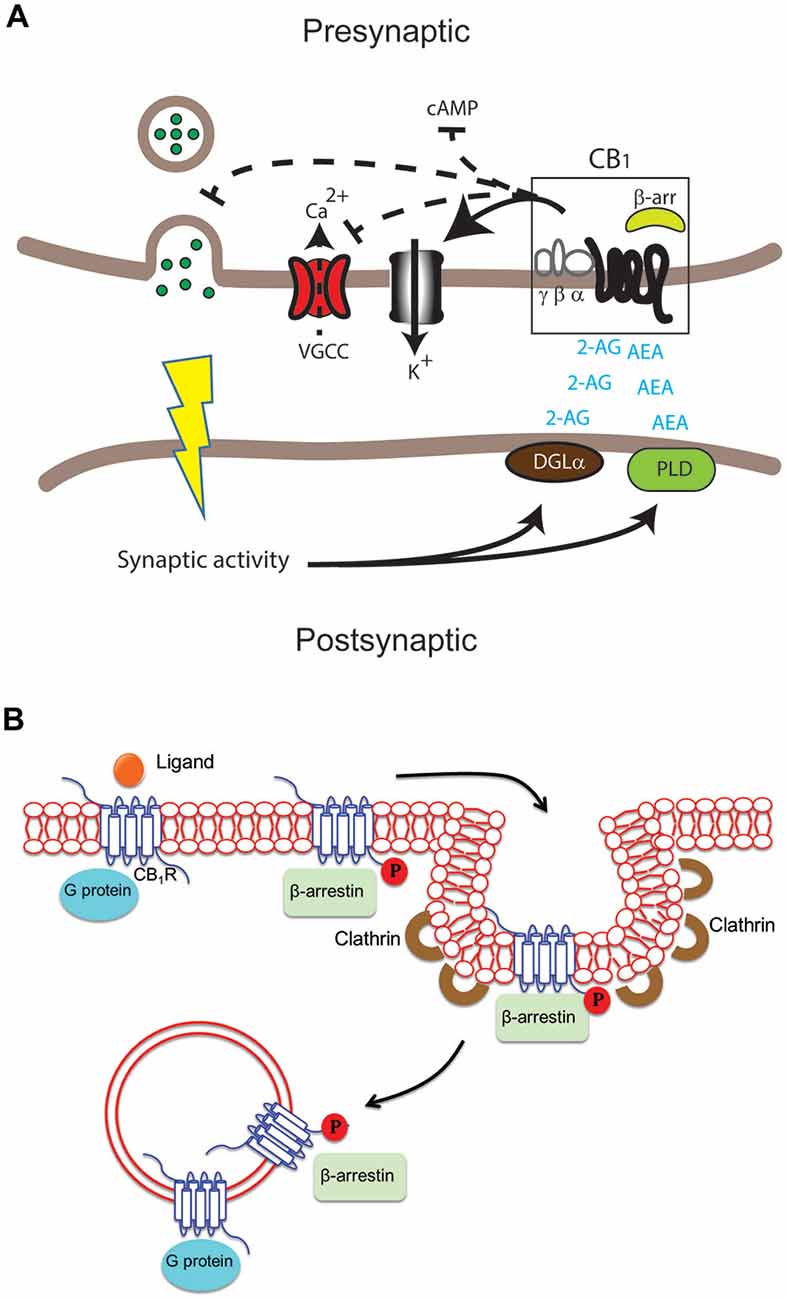

CB1 and CB2 receptors are G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) that help control pain, mood, and immune function [3]. When endocannabinoids like AEA or 2-AG attach to these receptors, they start a Gi/o protein signaling process, which leads to:

- Blocking adenylate cyclase (AC) → Lowers cAMP levels, slowing down cell activity.

- Reducing protein kinase A (PKA) activation → Less activation of other proteins inside the cell.

- Decreasing neurotransmitter release → Less glutamate, GABA, and dopamine are sent between brain cells.

But the effects of CB1 and CB2 activation depend on where they are located in the body. CB1 receptors in the brain and nervous system help regulate pain, mood, and neurotransmission by:

- Reducing glutamate & GABA release, altering pain perception and mood (leading to relaxation or, in some cases, anxiety).[4]

- Changing dopamine levels, which influences pleasure, motivation, and addiction.

- Activating potassium (K+) channels and blocking calcium (Ca2+) channels, making neurons less excitable—reducing pain but sometimes causing drowsiness.

Meanwhile, CB2 receptors in the immune system and peripheral tissues focus on reducing inflammation and regulating immune responses by:

- Lowering immune cell activity, which helps control inflammation.

- Modulating chronic pain and autoimmune diseases, calming an overactive immune system.

Therefore, selective signaling is essential for ensuring these processes remain controlled and beneficial. Without it, the ECS could become overactive or unbalanced.

β-Arrestin Pathway and CB1 Receptor Regulation

When CB1 receptors are overstimulated, such as with excessive THC use, the β-arrestin pathway helps regulate their activity to prevent overstimulation and build-up of tolerance. [5] This happens through three key processes:

- Desensitization: β-arrestin attaches to the CB1 receptor, blocking it from sending signals and reducing its activity.

- Internalization: The receptor is pulled inside the cell through clathrin-coated vesicles, making it temporarily inactive.

- Downregulation and Tolerance: If CB1 receptors stay internalized for too long, they may be broken down instead of recycled, leading to fewer receptors available for activation. This makes the body less responsive to THC over time, requiring higher doses to achieve the same effects.

Figure 1: Shows how GPCR signaling is regulated and how β-arrestin affects CB1 receptors. (a) When an agonist binds, GPCRs activate G proteins. (b) GRK phosphorylates the receptor, allowing β-arrestin to bind and stop signaling (desensitization). (c) β-arrestin helps remove the receptor through clathrin-coated vesicles for recycling or breakdown. With too much THC, CB1 receptors may be broken down instead of reused, reducing their numbers and leading to tolerance. [6]

But, if CB1 receptors are overstimulated too often, this desensitization can lead to tolerance, meaning the user will need more of the substance to experience the same effect. Over time, this could increase the risk of dependence. Since excessive β-arrestin activation plays an important role in this process, researchers are looking for ways to fine-tune CB1 receptor signaling.

This is where ligand bias comes in. Instead of activating all pathways equally, ligand bias allows for more accurate control, favoring beneficial signaling while minimizing unwanted effects.

Ligand Bias: Activating the Right Pathway

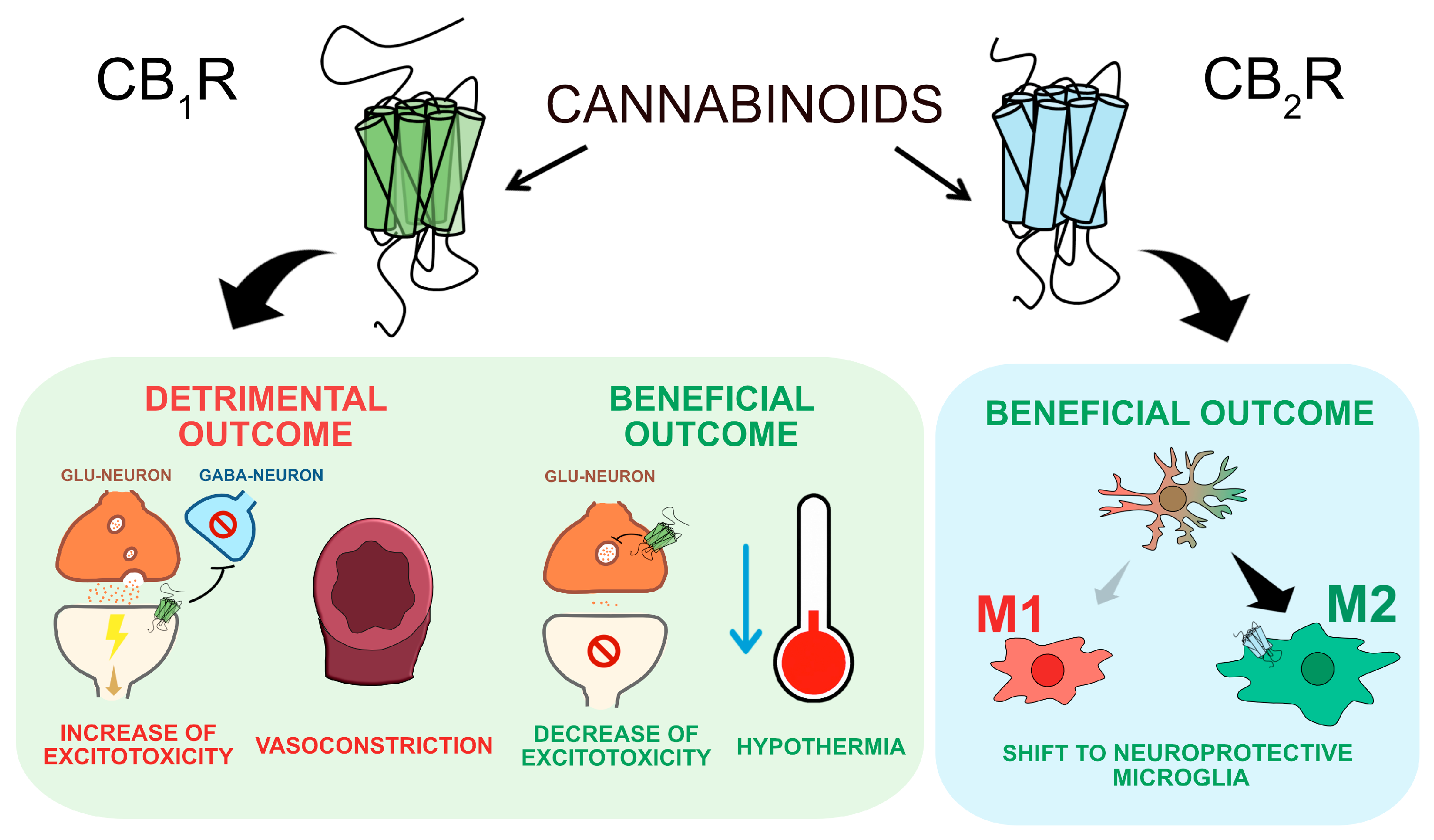

CB1 receptors don’t always respond the same way to different molecules. Some activate the G-protein pathway, which helps with pain relief, while others activate the β-arrestin pathway as shown in figure 2, which can lead to tolerance and side effects.

- G-protein signaling → Helps with pain & inflammation

- β-arrestin pathway → Leads to tolerance & side effects

This idea, called ligand bias (biased agonism), is helping scientists develop better treatments. By creating drugs that only activate the helpful G-protein pathway while avoiding too much β-arrestin activation, we can improve pain relief and neuroprotection without causing tolerance or unwanted effects.

Figure 2. Ligand-Biased Signaling in CB1 and CB2 Receptors. This figure shows ligand-biased signaling in CB1 and CB2 receptors, where ligands primarily activate either the G protein pathway or the β-arrestin pathway, leading to different cellular responses. Antagonists block both pathways by preventing ligand binding.[7]

Selective Signaling in Neurodegenerative Diseases

Neurodegenerative diseases like multiple sclerosis (MS), Huntington’s disease (HD), and Alzheimer’s disease (AD)are linked to problems in the endocannabinoid system (ECS). The CB1 receptor plays an important role in protecting the brain, but if it is overused, the body can build tolerance, making treatments less effective.

Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

✔ CB1 activation helps reduce brain inflammation, muscle stiffness, and pain.

✔ Sativex (a THC-CBD spray) improves movement and reduces symptoms in MS patients.[8]

✔ According to the paper “Cannabinoid Receptors in the Central Nervous System: Their Signaling and Roles in Disease” studies on CB1-deficient mice show increased brain damage, proving that CB1 protects neurons. [9]

Huntington’s Disease (HD)

✔ CB1 receptors start disappearing early in the disease, even before symptoms appear.

✔ Losing CB1 receptors makes movement problems worse and leads to faster brain cell damage.

✔ CB1 activation increases BDNF (Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor), which helps protect brain cells and supports neuron survival. [9]

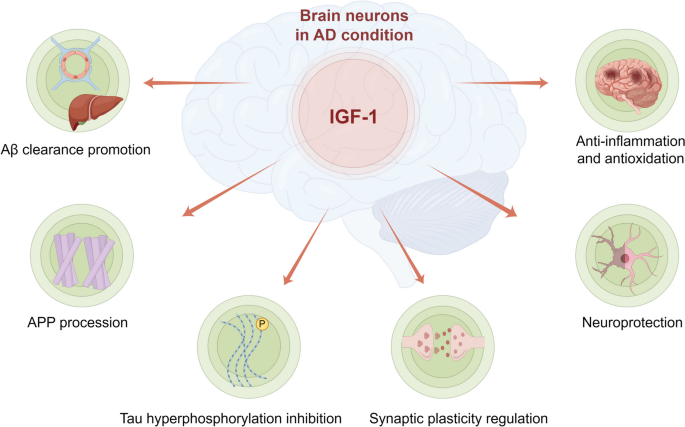

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD)

✔ CB1 activation helps clear harmful β-amyloid buildup, which is linked to memory loss in AD.

✔ Mice without CB1 receptors have worse memory problems, showing that CB1 is needed for brain function.

✔ CBD helps protect the brain by reducing tau buildup, which contributes to neuron damage. [9]

In diseases like MS, HD, and AD, selective CB1 activation can help protect brain cells and improve symptoms. However, too much activation can lead to tolerance, making treatments less effective over time.Therefore, Selective signaling plays an important role in ensuring that CB1 receptors are activated only when and where needed, allowing scientists to develop more effective therapies with fewer side effects.

What Happens When Selective Signaling Fails?

Without selective signaling, the body could suffer from several issues:

- Increased side effects: If CB1 receptors are overstimulated in the brain, it could lead to memory loss, confusion, and impaired motor function. Overstimulation of CB2 receptors might suppress the immune system too much, making us vulnerable to infections.

- Uncontrolled pain and inflammation: Without selective signaling, the body could either feel too much pain in some areas or too little in others. Pain relief might not be targeted properly, leaving some areas of the body still suffering.

- Tolerance and receptor burnout: With constant activation of CB1 receptors, they can become desensitized. This means a person may need higher doses to achieve the same effect, which increases the risk of addiction and worsens the overall response.

- Mood disruptions: Overactivation of the ECS could lead to psychological side effects like anxiety, paranoia, or depression.

Therefore, without selective signaling, the ECS would lose its ability to finely tune processes, and the body would suffer from overactivation or underactivation of critical pathways.

The Bottom Line: Balance Is Key

And the endocannabinoid system (ECS) plays a vital role in regulating key functions like pain, mood, and immune response. It’s like the body’s internal balancing act, making sure everything runs smoothly. But here’s the catch: when the ECS doesn’t work properly, it can lead to serious issues, from chronic pain to mood swings and even disorders like anxiety or inflammation. Without proper regulation, things can get out of control fast!

Therefore, by understanding how selective signaling works in the ECS, we can create better treatments that target exactly what’s needed without all the side effects. So, why should you care? Because the ECS affects everyone! Whether you’re dealing with pain, stress, or just want to stay healthy as you age, learning more about how the ECS works could lead to safer, smarter treatments for a better life. And who wouldn’t want that?

Footnotes

[1] Lu, H. C., & Mackie, K. (2016). An Introduction to the Endogenous Cannabinoid System. Biological psychiatry, 79(7), 516–525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.07.028

[2] Bosier, B., Muccioli, G. G., Hermans, E., & Lambert, D. M. (2010). Functionally selective cannabinoid receptor signalling: therapeutic implications and opportunities. Biochemical pharmacology, 80(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2010.02.013

[3] Howlett, A. C., & Abood, M. E. (2017). CB1 and CB2 Receptor Pharmacology. Advances in pharmacology (San Diego, Calif.), 80, 169–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.apha.2017.03.007

[4] Patel, S., & Hillard, C. J. (2009). Role of endocannabinoid signaling in anxiety and depression. Current topics in behavioral neurosciences, 1, 347–371. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-88955-7_14

[5] Nguyen, P. T., Schmid, C. L., Raehal, K. M., Selley, D. E., Bohn, L. M., & Sim-Selley, L. J. (2012). β-arrestin2 regulates cannabinoid CB1 receptor signaling and adaptation in a central nervous system region-dependent manner. Biological psychiatry, 71(8), 714–724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.11.027

[6] Whalen, E. J., Rajagopal, S., & Lefkowitz, R. J. (2011). Therapeutic potential of β-arrestin- and G protein-biased agonists. Trends in Molecular Medicine, 17(3), 126-139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmed.2010.11.004

[7] Ye, L., Cao, Z., Wang, W., & Zhou, N. (2019). New Insights in Cannabinoid Receptor Structure and Signaling. Current Molecular Pharmacology, 12(3), 239–248. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874467212666190215112036

[8] Russo, M., Calabrò, R. S., Naro, A., Sessa, E., Rifici, C., D’Aleo, G., Leo, A., De Luca, R., Quartarone, A., & Bramanti, P. (2015). Sativex in the management of multiple sclerosis-related spasticity: role of the corticospinal modulation. Neural plasticity, 2015, 656582. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/656582

[9] Kendall, D. A., & Yudowski, G. A. (2017). Cannabinoid Receptors in the Central Nervous System: Their Signaling and Roles in Disease. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 10(294). https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2016.00294