Schizophrenia is a neurodegenerative disease that over 2.6 million American have, although over 40 percent of them are untreated. While there are a lot of movies and other popular media that depict the disease, they often paint a false portrait. There is a general lack of understanding in the science community regarding the disease. We can conclude there is a disruption in the development of the brain and a possible malfunction in signaling pathways. Scientists are exploring the pathogenesis and possible treatments of this terrible disease.

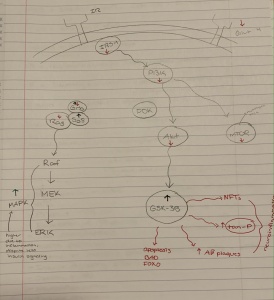

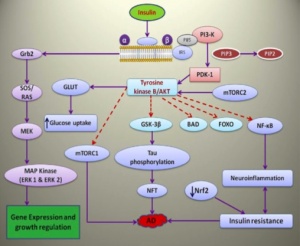

Wnt/GSK/B-Catenin

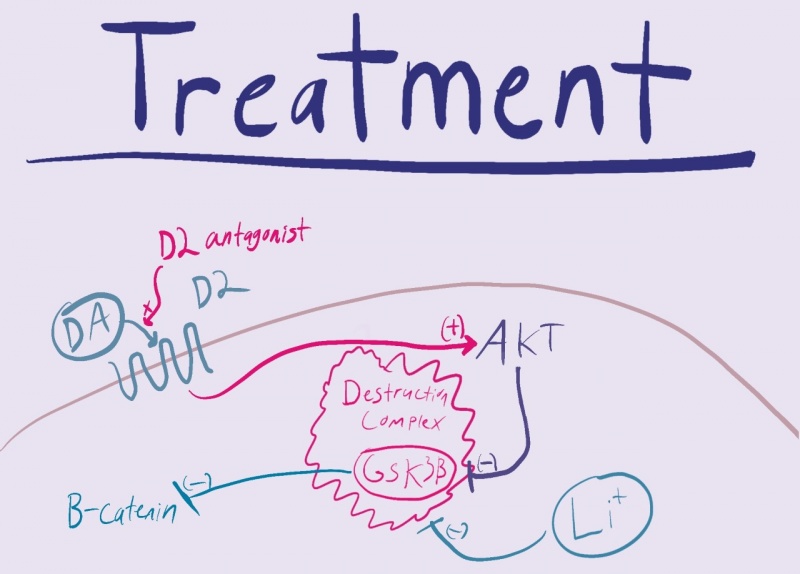

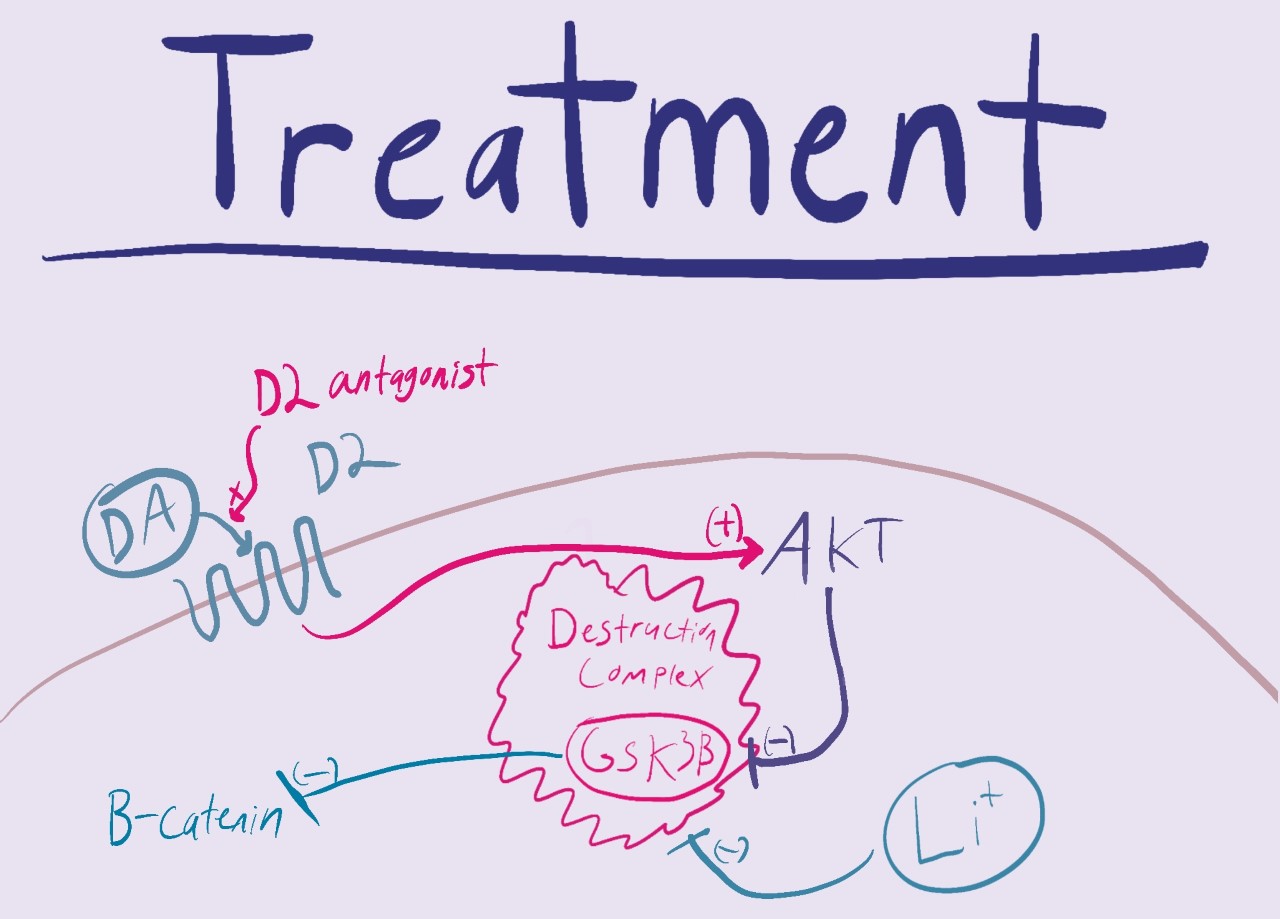

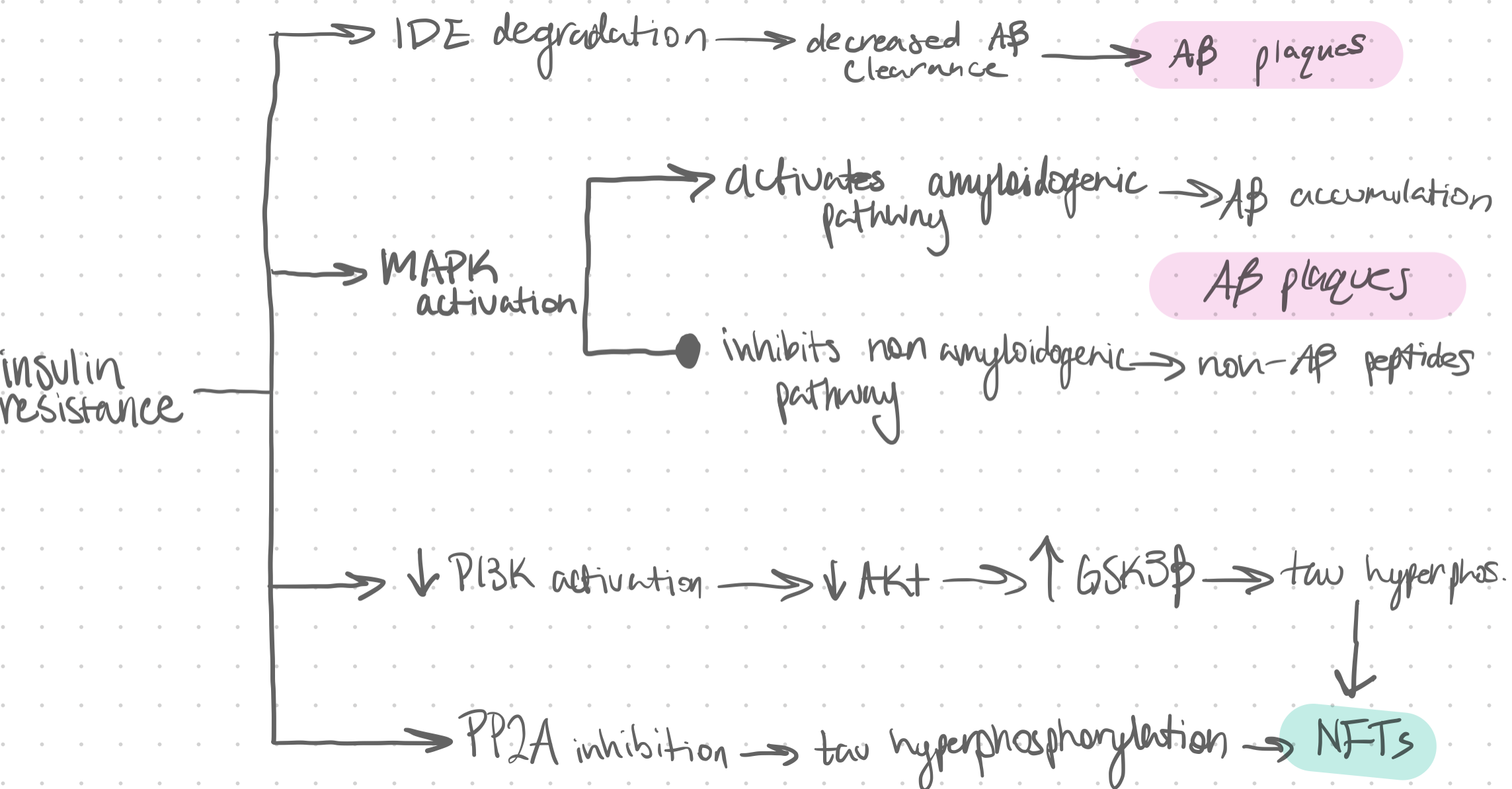

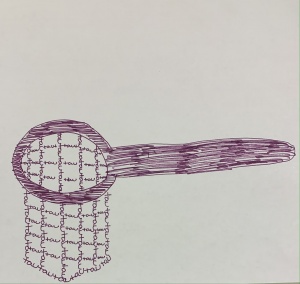

In the development of the brain one pathway is especially important. The Wnt/GSK pathway is important in the development of organs and the mammalian brain. In adults the canonical pathway is influential in cell proliferation and STEM cell homeostasis. Under normal conditions the aptly named destruction complex phosphorylates and degrades the protein B-Catenin. When Wnt receptors are activated the destruction complex and its protein kinase, GSK, are bound to the cell membrane. This allows B-Catenin to penetrate the nucleus and transcribe DNA leading to cell growth and proliferation.

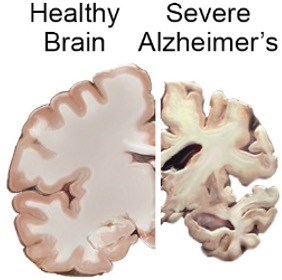

A disruption in this Wnt pathway is evident in the pathology of schizophrenia. With no Wnt activation the destruction complex runs wild, phosphorylating B-Catenin and preventing cell division and proliferation. As this pathway is important in the development of the brain, a change in the early stages of life would be increasingly detrimental. This makes sense in the pathology of schizophrenia in which we see a change in the anatomy of the brain. The brains of people with developed Schizophrenia have far less active and healthy brain tissue which can be attributed to a dysfunctional Wnt pathway.

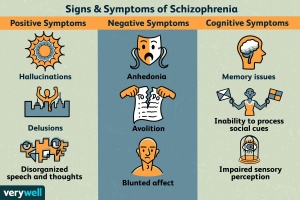

What are the symptoms of this disruption?

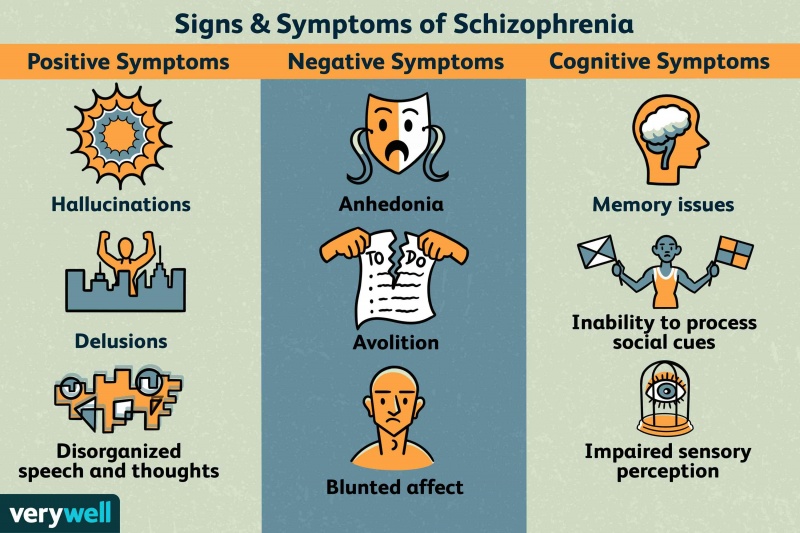

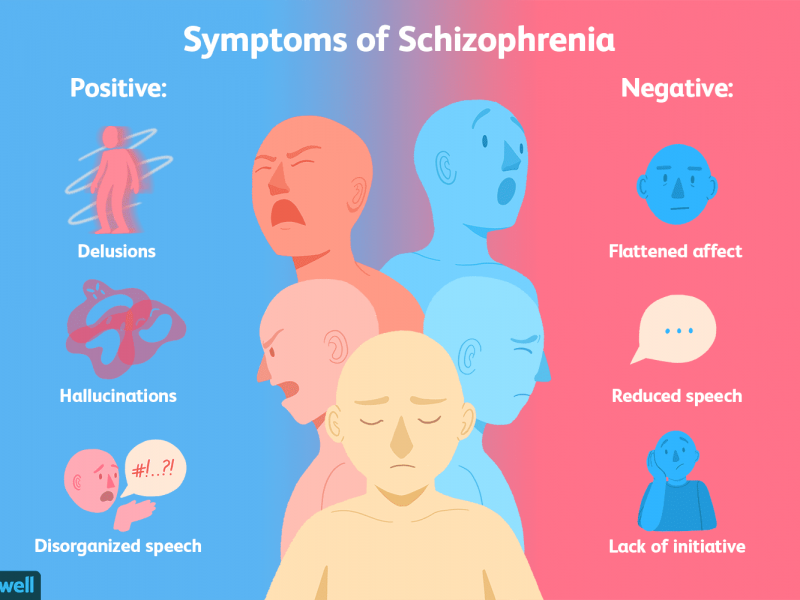

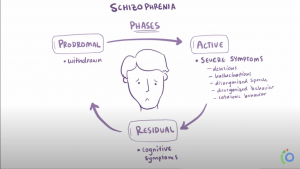

In Schizophrenia there are both positive and negative symptoms. Positive symptoms are the commonly known, they include patients hearing voices, having imaginary people in their lives, or other allusions of the grander. These are the symptoms we see in movies that depict mostly unrealistic imaginations or fantastical conspiracies. In reality the majority of patients are somewhat functional and aware. Negative symptoms include a lack of motivation, sloth, and flatness in personality. While the disease seems to be a consequence of early developmental issues the symptoms don’t show until late adolescence or young adulthood.

Treatments

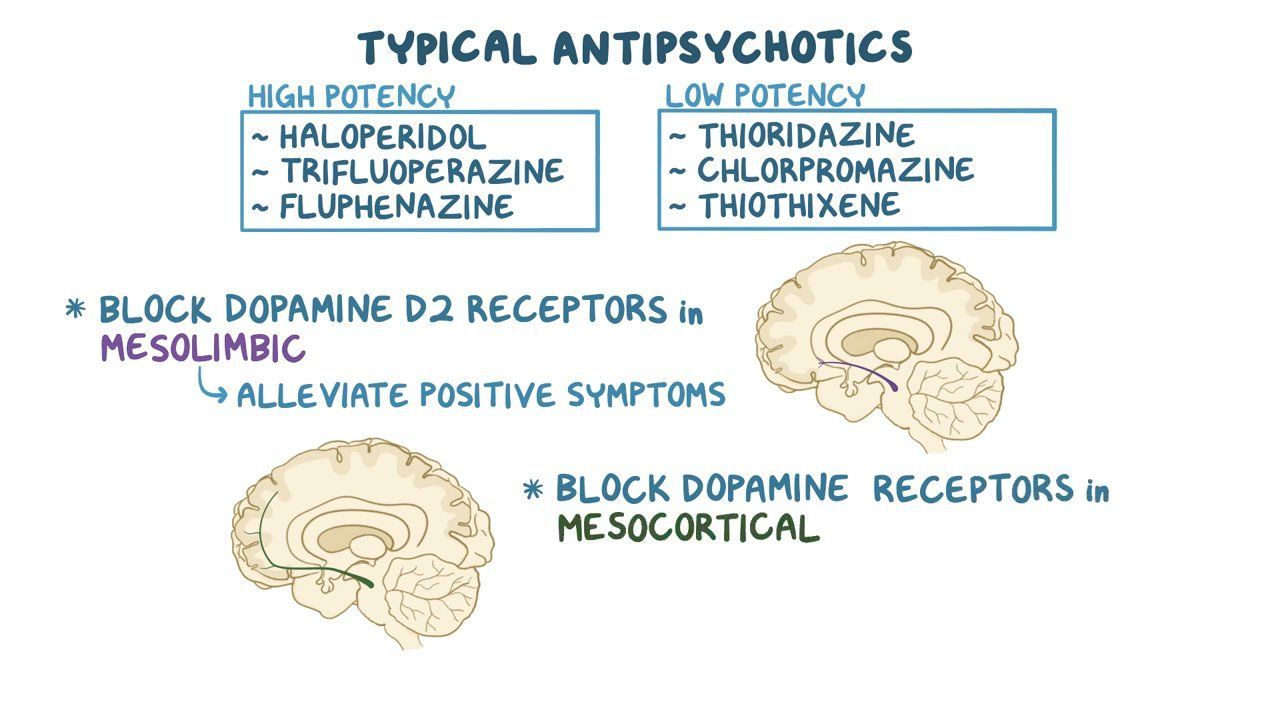

There are a couple different treatment options available to those who have this disease. The first being antipsychotics, which are ridden with side effects and consequentially a lack of patient compliance. Another treatment option is lithium. While more common in the treatment of bipolar disorder, it works by inhibiting GSK which is a source of the pathogenesis of schizophrenia.

Origin

These dysfunctions in the brain development and signaling pathways can be attributed to many different things. Drug use by both the individual and their mother is linked to increased chances of developing the disease. Genetic mutations and nucleotide variations caused by stimuli in the environment can also increase hour chances of getting schizophrenia. There needs to be and is more research being done on genetic implications with the disease.

Conclusion

Schizophrenia is a neurodegenerative disease where there is a disruption in the development of the brain and a possible malfunction in signaling pathways. A disruption in this Wnt pathway is evident in the pathology of schizophrenia. There are a couple different treatment options available to those who have this disease although they are not very affective. Further research is needed to help solve this health crisis and bring relief to millions of affected individuals

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/psychosis-vs-schizophrenia-5095195_final-42cb304e269948519136e8f0f4cdc0da.jpg)