As cannabis is becoming legal throughout most of the USA, this makes researchers wonder what role cannabis plays in obesity. Obesity is a complex disease that involves an excessive about of body fat. There are many reasons why someone may become obese. But no matter why or how someone became obese, it still has the same end result, and can increase the risk of other diseases and health concerns. So what is going on in the brain that might be a cause of obesity?

Normal Functioning Pathway

Normal Functioning Pathway

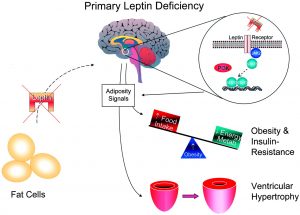

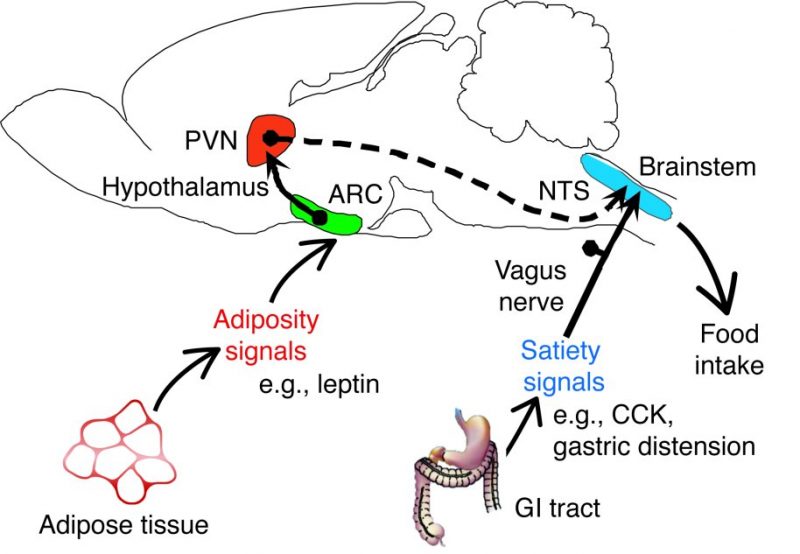

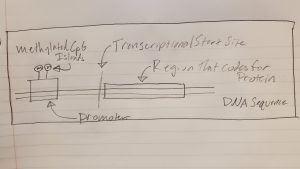

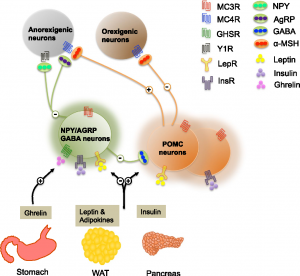

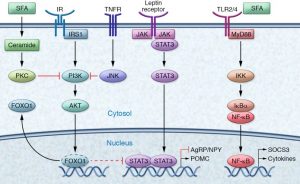

To start off, there are two key players in the brain that control appetite in the pathway that we will be focusing on. These are the hormones leptin and insulin. First, lets talk about leptin. Leptin is released from brain cells after food is consumed, this then binds to and activates leptin receptors on other brain cells. The activated leptin receptor then activates proteins called Janus kinases (JAK) which in turn activate signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) proteins. STAT enters the brain cell’s nucleus and causes certain portions of DNA to be transcribed into proteins. These proteins transfer signals to brain cells in the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus is a central brain region that controls thirst and hunger among other things. These signals inhibit the orexigenic pathway, which lets you know that you are hungry. Or activates the anorexigenic pathway, which tells you that you are full. Overall, leptin regulates fat storage in the body by letting you know when you are hungry or full.

Now, let’s talk about insulin. Insulin is released from brain cells after food is consumed. Insulin then binds to and activates insulin receptors on the outside of other brain cells. The insulin receptors activate a protein called IRS1, which in turn activates a many other proteins ending in protein kinase B (Akt). Akt enters the brain cell’s nucleus and causes protein FOXO1 to leave the nucleus. When FOXO1 leaves the nucleus, STAT activity is activated by proteins. This in turn helps you feel full. Overall, insulin helps you feel full, but if there is not enough insulin, this can lead to overeating.

High-Fat Diet

High-Fat Diet

High saturated fatty acid diets negatively affects the way the brain controls appetite. First, saturated fatty acids (SFAs) enter the brain and bind to TLR receptors. These receptors then become activated which in turn activates a protein called IKK. IKK then releases NF-κB which enters the nucleus. NF-κB causes SOCS3 proteins to inhibit the insulin and leptin signaling pathways described previously. Overall, stopping your brain from letting you know that you are full even if you have been eating. This is an issue because it results in overeating.

A high fat diet also leads to inflammation in the brain. This happens because consumption of high fat foods release proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α which then bind to TNF receptors. These receptors activate protein JNK which then inhibits IRS1. IRS1 prevents insulin signaling which in return causes more hunger. Therefore, high fat diets cause bodily inflammation, as well as insulin and leptin resistance. Ultimately, preventing the feeling of being full, resulting in weight gain. So what role does cannabis play in obesity?

Cannabis and Obesity

First, most people know that exposure to cannabis produces an increase of appetite, commonly known as the “munchies”. This led to one study where researchers explored the role of the brains natural endocannabinoid system in the regulation of obesity. They ended up developing a successful therapeutic for obesity by blocking the cannabinoid CB1 receptors using ligands, such as Rimonabant, to produce weight loss. Although this approach worked, Rimonabant was associated with increased rates of depression and anxiety and therefore removed from the market.

Recently, it was also discovered that obesity is ironically much lower in cannabis users as compared to non-users. Therefore, although cannabis can cause the munchies, it can also lower body fat. So, the researchers propose that tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) or a THC/cannabidiol combination drug may produce weight loss, and may be useful for the treatment of obesity. Further research is needed to show exactly why cannabis is causing this paradoxical outcome.

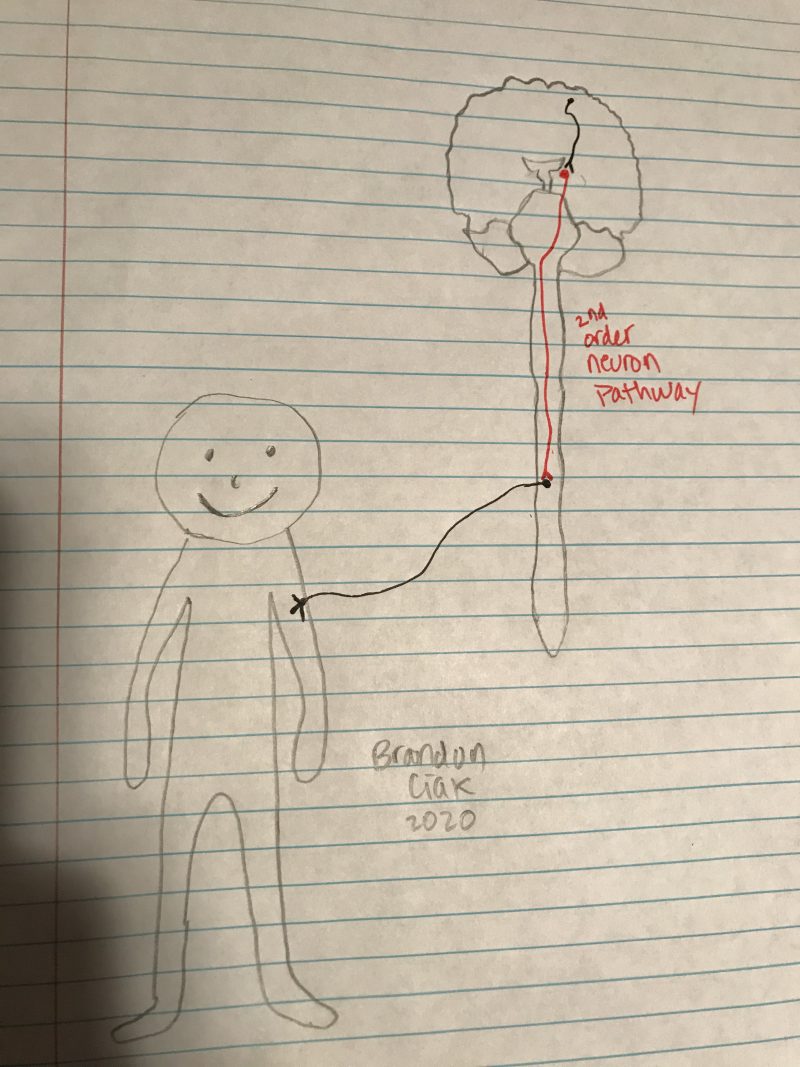

environment around us. Generally, we can think of these neurons communicating body wide, with first-order neurons receiving the signals from our limbs and ultimately transferring them up to the brain with the help of second motor neurons that act as an “intermediate”, running the signal up the spinal cord and to the brain before sending the message to another neuron.

environment around us. Generally, we can think of these neurons communicating body wide, with first-order neurons receiving the signals from our limbs and ultimately transferring them up to the brain with the help of second motor neurons that act as an “intermediate”, running the signal up the spinal cord and to the brain before sending the message to another neuron. Of course, there are more pathways and functions that get carried out by each of the structures listed above, but what if an area of this pathway, let’s say the pathway of the second-order neurons, is damaged or gets out of whack? What then could happen? Damages to the PVN or just the pathway these neurons take to inform the brainstem of continual eating will be unable to function properly and may lead to issues such as overeating or even undereating. The damage or loss of these second-order neurons may even impact some of the inflammation regulator proteins such as

Of course, there are more pathways and functions that get carried out by each of the structures listed above, but what if an area of this pathway, let’s say the pathway of the second-order neurons, is damaged or gets out of whack? What then could happen? Damages to the PVN or just the pathway these neurons take to inform the brainstem of continual eating will be unable to function properly and may lead to issues such as overeating or even undereating. The damage or loss of these second-order neurons may even impact some of the inflammation regulator proteins such as

The way the brain controls appetite and food cravings changes substantially after consuming foods high in fat. Like many “bad” habits, eating high-calorie, high-fat foods can be difficult to stop once you’ve become accustomed to the diet—

The way the brain controls appetite and food cravings changes substantially after consuming foods high in fat. Like many “bad” habits, eating high-calorie, high-fat foods can be difficult to stop once you’ve become accustomed to the diet— The

The

It has been found that there are a number of ways in which food, specifically food that is high in fat, can have addictive qualities. In some ways this assertion is already intuitive, as you never just want to have

It has been found that there are a number of ways in which food, specifically food that is high in fat, can have addictive qualities. In some ways this assertion is already intuitive, as you never just want to have  drug addicts, where cortical brain regions involved in executive control and decision making have been heavily implicated. Through eating a high fat diet, we might be allowing our brains to think that eating more high fat items is what should occur.

drug addicts, where cortical brain regions involved in executive control and decision making have been heavily implicated. Through eating a high fat diet, we might be allowing our brains to think that eating more high fat items is what should occur.

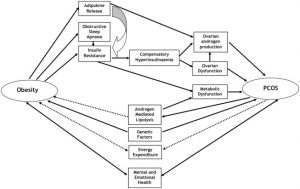

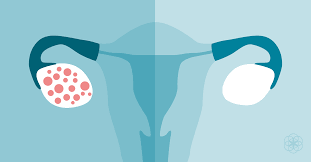

agile balance that is maintained between estrogen, progesterone, and the androgens. This hormonal imbalance often results in the development of cysts within the ovaries, contributing to irregular menstrual cycles, infertility, and anxiety/depression. Additionally, overproduction of these androgens leads to excess hair all over the body, acne, and insulin resistance and obesity.

agile balance that is maintained between estrogen, progesterone, and the androgens. This hormonal imbalance often results in the development of cysts within the ovaries, contributing to irregular menstrual cycles, infertility, and anxiety/depression. Additionally, overproduction of these androgens leads to excess hair all over the body, acne, and insulin resistance and obesity.