Most everyone has heard of Alzheimer’s Disease, far too often because of personal experience with loved ones. Although everyone associates the disease with someone losing their memory (and rightfully so), a physiological hallmark of Alzheimers is insulin resistance, which is thought of as the state of not having enough insulin, for one reason or another.

Insulin is most commonly known for its role in regulating metabolism. Insulin however, does a whole host of other helpful things for our bodies, including the regulation of synaptic plasticity, being neuroprotective, acting on neuronal growth and survival, and has been proposed to regulate the gene expression required for the ability to consolidate long term memories. All of this alludes to the fact that if we don’t have enough insulin, as seen in Alzheimers, we have a problem.

What can we do?

Insulin resistance has been observed to occur due to an inhibited insulin signalling pathway and an overactive pathway that leads that resistance called mTOR1 (mammalian target of rapamycin). However, with a drug called Rapamycin, mTOR can be inhibited and insulin resistance is abolished. Now, this doesn’t solve Alzheimers, but it’s certainly a step in the right direction for treatment if nothing else.

Some researchers however are suggesting that rapamycin has additional beneficial effects than simply increasing insulin (although this still might be the mechanism, the benefits are broader than simply treating Alzheimers). One of the positive  effects of rapamycin that was found was that, when intermittently administered, rapamycin led to stem cell regeneration. Considering some of the applications for stem cells, this is an amazing discovery that could have far reaching implications on the future of medicine. And that’s potentially just the tip of the iceberg. Because of the mTOR1 inhibition through rapamycin, it has been found that there is a decreased risk of cancer, since mTOR1 signaling can lead to cell proliferation. Tumor regression has also been observed to occur. It’s also been found that mTOR1 signalling sometimes leads to misfolded proteins. Using rapamycin, inhibiting mTOR1 led to greater autophagy and suppression of protein synthesis, which is important because this means that rapamycin can have neuroprotective effects in not just Alzheimers, but also Parkinson’s Disease and Huntington’s Disease.

effects of rapamycin that was found was that, when intermittently administered, rapamycin led to stem cell regeneration. Considering some of the applications for stem cells, this is an amazing discovery that could have far reaching implications on the future of medicine. And that’s potentially just the tip of the iceberg. Because of the mTOR1 inhibition through rapamycin, it has been found that there is a decreased risk of cancer, since mTOR1 signaling can lead to cell proliferation. Tumor regression has also been observed to occur. It’s also been found that mTOR1 signalling sometimes leads to misfolded proteins. Using rapamycin, inhibiting mTOR1 led to greater autophagy and suppression of protein synthesis, which is important because this means that rapamycin can have neuroprotective effects in not just Alzheimers, but also Parkinson’s Disease and Huntington’s Disease.

One of the most interesting positive effects found from administration of rapamycin was its ability to increase the lifespan of rats that were treated with the drug. It does this through slowing down the aging process along with inhibiting metabolic or neoplastic diseases. This also potentially includes cancer, as regulating cell proliferation through the drug means that cancer cells can’t spread as rapidly, and cancer cells may also happen less in the first place.

Before we all start taking insulin, it’s important to remember however that one of the most consequential aspects of a drug’s effects and effectiveness is the dosage and how often its administration. With rapamycin, the appropriate ratios of both of these factors are still unknown as of yet, but research is being done to try decipher further how to access the perceived positive effects of the drug. It has been seen though that rapamycin doesn’t fully inhibit mTORC1 processes, and so a combination with another treatment would more effectively implement the positive effects of Rapamycin.

Before we all start taking insulin, it’s important to remember however that one of the most consequential aspects of a drug’s effects and effectiveness is the dosage and how often its administration. With rapamycin, the appropriate ratios of both of these factors are still unknown as of yet, but research is being done to try decipher further how to access the perceived positive effects of the drug. It has been seen though that rapamycin doesn’t fully inhibit mTORC1 processes, and so a combination with another treatment would more effectively implement the positive effects of Rapamycin.

This being said, there are observed downsides, which shouldn’t ever be overlooked within any kind of drug treatment. Rapamycin has been sometimes seen to actually  increase insulin resistance, but the mechanism for why this occurs is speculated to be known (inhibition of mTOR2). Other negative effects included increased hyperglycemia within type 2 diabetes mouse models, and the ability for tumors to start regrowing after treatment with rapamycin stopped.

increase insulin resistance, but the mechanism for why this occurs is speculated to be known (inhibition of mTOR2). Other negative effects included increased hyperglycemia within type 2 diabetes mouse models, and the ability for tumors to start regrowing after treatment with rapamycin stopped.

To end on a positive note about rapamycin treatment, there are no known overdose deaths due, which could signify that the ability for researchers to manipulate administered dosage levels could be rather high. All in all, more research into the side-effects and anti-aging effects of rapamycin are needed, but some people even now think that rapamycin can be used as an effective anti-aging (or at least an anti-disease) drug with very few discovered side-effects.

In The Brain

In The Brain CBD Vs. THC?

CBD Vs. THC?

develop depressive symptoms afterward, which is quite a dramatic number. Another fact that was found is equally concerning: one study found that after only a mild traumatic brain injury, there was a 15% chance that the person developed major depression. This is the lightest and least serious type of brain injury (which you can get simply by hitting your head slightly too hard) and the worst, most serious type of depression, occurring in more than 1 in 7 people who experience a concussion. This is significant not only because of the depression part, but because this points to concussion as being more than purely “an annoyance”. In fact, the total prevalence across all severities of TBIs for major depression is 14-29%. In other words, up to a third of people who experience a concussion develop the clinically-worst type of depression.

develop depressive symptoms afterward, which is quite a dramatic number. Another fact that was found is equally concerning: one study found that after only a mild traumatic brain injury, there was a 15% chance that the person developed major depression. This is the lightest and least serious type of brain injury (which you can get simply by hitting your head slightly too hard) and the worst, most serious type of depression, occurring in more than 1 in 7 people who experience a concussion. This is significant not only because of the depression part, but because this points to concussion as being more than purely “an annoyance”. In fact, the total prevalence across all severities of TBIs for major depression is 14-29%. In other words, up to a third of people who experience a concussion develop the clinically-worst type of depression.

The app essentially functions as a gamified symptoms journal, where concussed individual reports symptoms and feelings, then the app turns those inputs into a game-like version of their feelings. This can help avoid social isolation associated with concussion recovery, especially since concussion patients are urged not to do anything that may be detrimental to their recovery. Within the app, users could form a network around their symptom log and comment and interact with other users’ posts, generating a cohesiveness between patients that may be looking for some more interaction when able. The main takeaway here is that, while you shouldn’t be overstimulating your brain and harming recovery, you can use what little screen time you have in a positive manner, leading to a more efficient recovery.

The app essentially functions as a gamified symptoms journal, where concussed individual reports symptoms and feelings, then the app turns those inputs into a game-like version of their feelings. This can help avoid social isolation associated with concussion recovery, especially since concussion patients are urged not to do anything that may be detrimental to their recovery. Within the app, users could form a network around their symptom log and comment and interact with other users’ posts, generating a cohesiveness between patients that may be looking for some more interaction when able. The main takeaway here is that, while you shouldn’t be overstimulating your brain and harming recovery, you can use what little screen time you have in a positive manner, leading to a more efficient recovery.

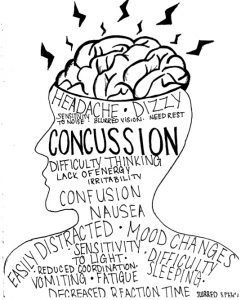

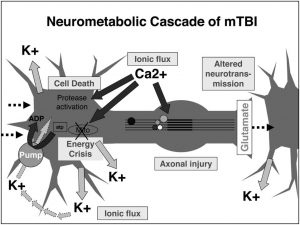

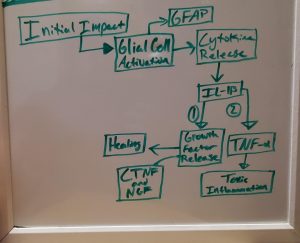

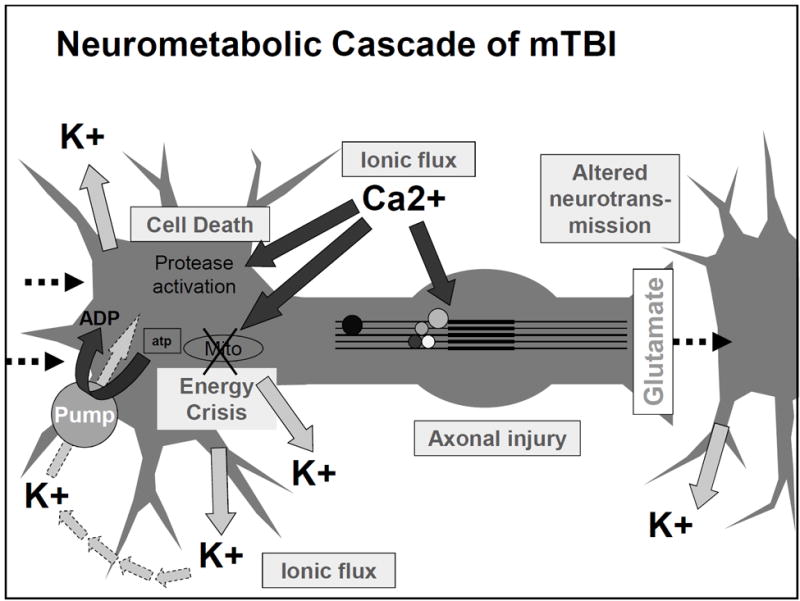

from behind, let’s examine what occurred microscopically inside of his brain as a result. The sudden movement inside his skull most likely started out with neurons becoming “leaky”, or more permeable for ions to flow in/out of the cell. For TBIs, there is an extreme influx of calcium and sodium ions with an efflux of potassium ions.

from behind, let’s examine what occurred microscopically inside of his brain as a result. The sudden movement inside his skull most likely started out with neurons becoming “leaky”, or more permeable for ions to flow in/out of the cell. For TBIs, there is an extreme influx of calcium and sodium ions with an efflux of potassium ions. body compared to the amounts being consumed intracellularly results in an unfavorable side product being formed with ATP (lactate) and extra calcium getting stored in the mitochondria. Shrinking and running out of options, these cells quickly realize that they are now only doing more harm than benefit and decide to turn to apoptosis: programmed cell death.

body compared to the amounts being consumed intracellularly results in an unfavorable side product being formed with ATP (lactate) and extra calcium getting stored in the mitochondria. Shrinking and running out of options, these cells quickly realize that they are now only doing more harm than benefit and decide to turn to apoptosis: programmed cell death. disruptions.

disruptions.

The changes described in the following list take place in neurons, which are brain cells that send signals to one another to let us think. Neurons are shaped a bit like an oak tree. Signals come into branches at the ‘top’ of the tree, travel down the neuron’s axon, which would be the tree’s trunk, and go out through the roots to the next neuron. The signal that comes into the branches is a neurotransmitter chemical. The neurotransmitter either tells a neuron to fire (which means to be activated and pass the signal on to the next neuron, which passes it to the next, and so on), or not to fire. If a neurotransmitter tells a neuron to fire, molecules that have positive or negative electric charges cross the cell membrane (a thin membrane like a water balloon that lets molecules go in and out) and change the voltage of the entire neuron. Becoming more and more

The changes described in the following list take place in neurons, which are brain cells that send signals to one another to let us think. Neurons are shaped a bit like an oak tree. Signals come into branches at the ‘top’ of the tree, travel down the neuron’s axon, which would be the tree’s trunk, and go out through the roots to the next neuron. The signal that comes into the branches is a neurotransmitter chemical. The neurotransmitter either tells a neuron to fire (which means to be activated and pass the signal on to the next neuron, which passes it to the next, and so on), or not to fire. If a neurotransmitter tells a neuron to fire, molecules that have positive or negative electric charges cross the cell membrane (a thin membrane like a water balloon that lets molecules go in and out) and change the voltage of the entire neuron. Becoming more and more  28.4% of people who suffer mTBI report an increase in aggression

28.4% of people who suffer mTBI report an increase in aggression