Memory is one of the most useful tools we have at our disposal. I’m sure you can come up with (from memory) countless examples right now of how memory has helped you live a better life than if you didn’t have it. Where did I last put my keys? How do I get to Target from here? What was that person’s name? All of these instances are incredibly useful for navigating everyday life, but there are also some times when memory is hindered, and for good reason.

When in immediate danger, things can be a blur, and after the fact it can be hard to remember a lot of the actual occurrences of the moment. It might seem counterintuitive at first to not be able to remember what transpired during a time of panic, but it does make a lot of sense evolutionarily. Flight or fight activates to allow you to survive immediate danger, and that means escaping or fighting. That doesn’t mean remembering the layout of the prowling tiger’s stripes, or what shade of grey the boulder was that was falling towards you from the cliffside. Memory in itself is important to survive, but if it happens to be the source of hindrance in which other things become more important in that moment in order to survive, it makes sense that it will be temporarily disabled.

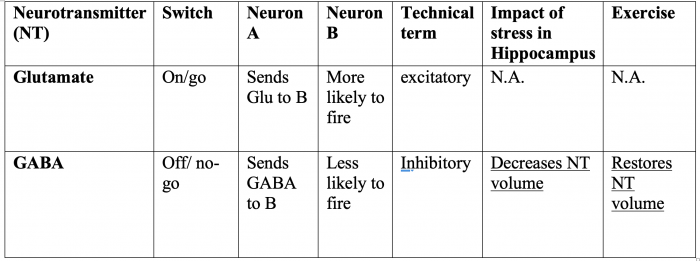

A phenomenon called LTP (Long-term potentiation) is what neurologically allows us to engage in a number of memory-related behaviors. LTP is thought to be one of the main components of storing long-term memories and is present in the brain’s ability to learn. The hippocampus, and specifically the dentate gyrus (DG) within the hippocampal formation, is crucial for memory formation through the use of LTP.

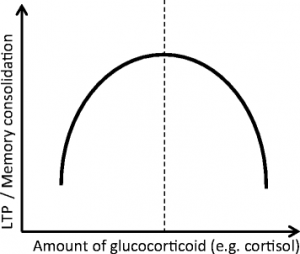

When stress is present, the ability to encode information (memory-wise) seems to be diminished, but several factors have to be addressed in order to further understand the relationship here. There are different types of stress, and which kind it is matters in trying to ascertain its impact on memory. Acute stress and chronic stress are the two main types that are mentioned in research, both names being self-explanitory. When either of the two types are present, LTP is virtually eliminated. There are some differences however: In chronic stress, LTP signalling in the hippocampal area of CA1 is imparied, while it has no effect on dentate gyrus function, though there have been other studies that showed the DG being imparied, specifically with unpredictable stress. In acute stress, signalling is a little more complicated, with some regions being facilitated with LTP, like the ventral hippocampus, while the dorsal hippocampus is inhibited. This speaks to the complexity of the task at hand of trying to discern the effect that stress has on brain systems.

Animal models for different neurological disorders, such as Alzhiemers disease and post traumatic stress disorder, have been trying to figure out the relation between the two, with interesting results. In AD animal models, there is naturally imparied LTP functioning, simply as a result of the degeneration. What was found with these animal models is that acute stress actually facilitates LTP, which is notable as this the opposite of normal, healthy brains. In PTSD animal models, researchers found that a single prolonged stress (SPS) induced LTP-like deficits in the hippocampus and amygdala, but there was an increase in contextual fear response memory.

There is certainly more to learn in this domain of research, but enough is known in the present moment to make informed decisions about the links between stress and memory.

initiate histone conformation that leads to gene transcription. The gene transcription creates event-associated memory

initiate histone conformation that leads to gene transcription. The gene transcription creates event-associated memory

looked at or thought about in a single day, every day! Our body does an incredible job at regulating processes, especially for something as important as transcription. For example, when a stressful event is induced in our environment, glutamate begins to accumulate by membrane transport proteins that will therefore let calcium inside of the cell. This leads to the MEK-ERK pathway each gaining a phosphate group which allows Elk-1 to become phosphorylated to start transcription regulation. The complete process, at much greater depth, can be found at the following link:

looked at or thought about in a single day, every day! Our body does an incredible job at regulating processes, especially for something as important as transcription. For example, when a stressful event is induced in our environment, glutamate begins to accumulate by membrane transport proteins that will therefore let calcium inside of the cell. This leads to the MEK-ERK pathway each gaining a phosphate group which allows Elk-1 to become phosphorylated to start transcription regulation. The complete process, at much greater depth, can be found at the following link:

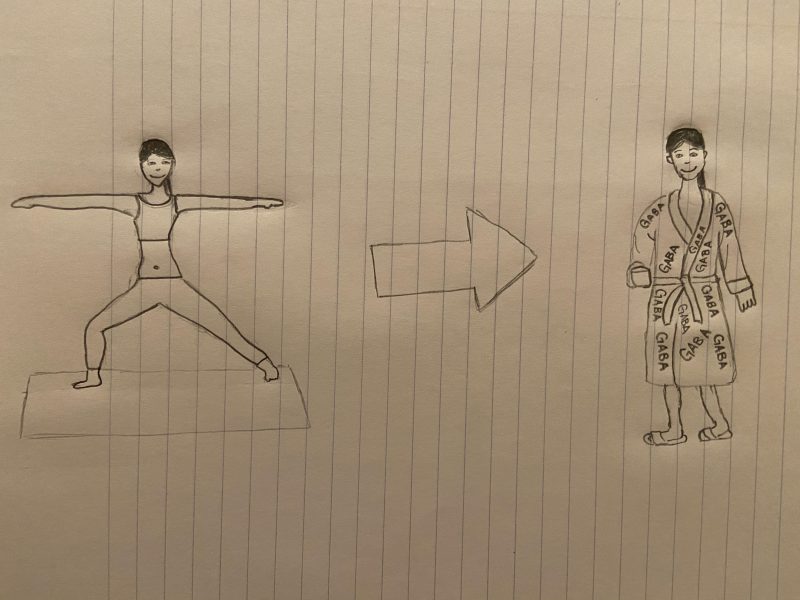

Voluntary Vs. Forced Exercise

Voluntary Vs. Forced Exercise