The short answer to that question is: yes, obesity can be considered a brain disease. However, I encourage you to read on further for the longer answer.

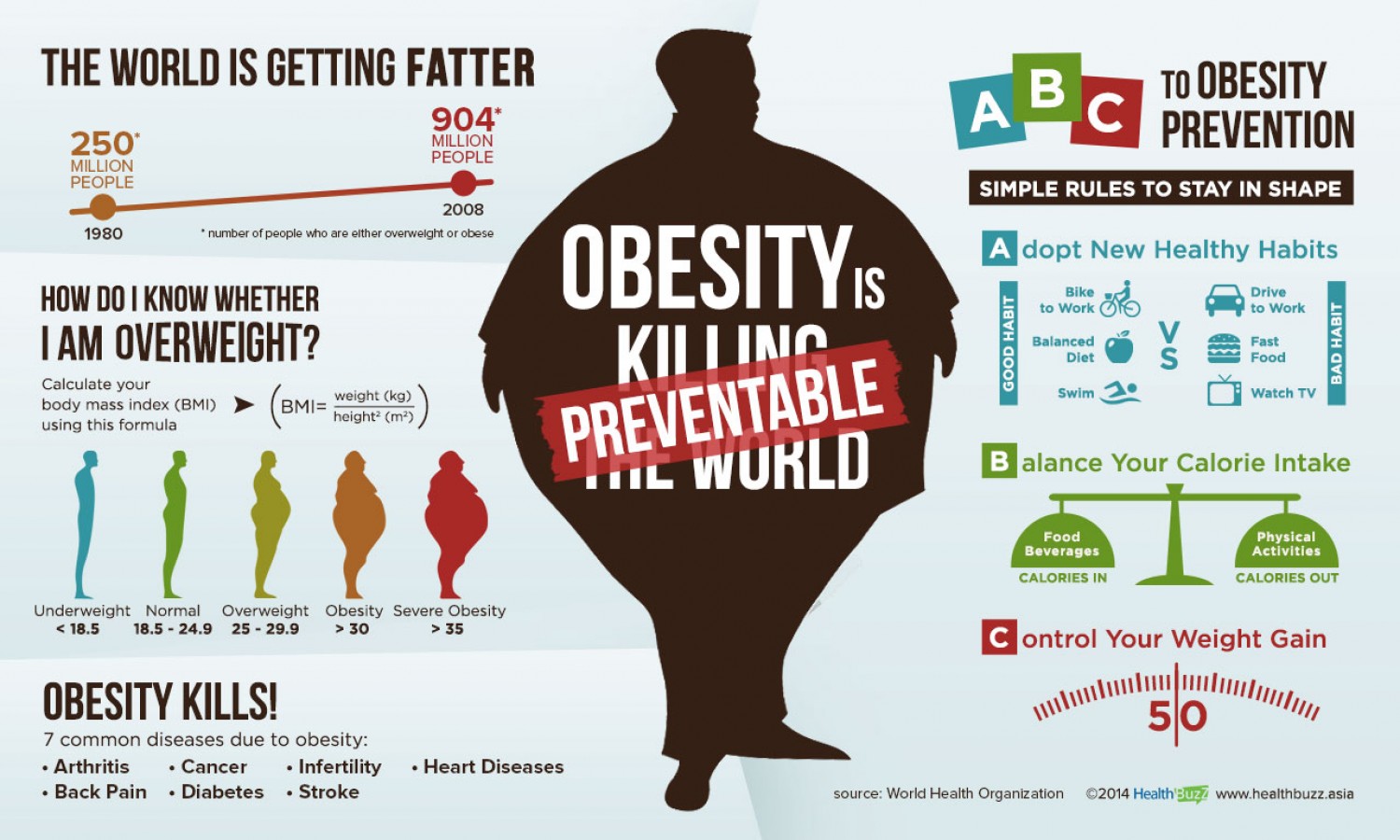

The Obesity Epidemic

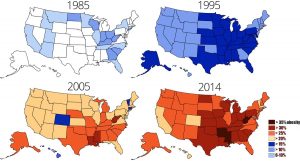

Nearly 34% of adults and 15-20% of children and adolescents in the United States are obese and the rates of obesity have nearly tripled in the past 50 years. The CDC defines obesity based on body mass index (BMI) values of 30 and higher. So what exactly is causing this increased prevalence of obesity? Is it due to our “go-go-go” lifestyle and thus increased consumption of fast foods? Are children becoming more obese because of the use of technology and screen time and are less physically active? These are both viable options, but we also need to discuss how obesity affects the brain.

Figure 1. The rise of obesity rates in the United States from 1985-2014. The blue color indicates lower obesity rates, whereas the orange/red color indicates higher levels of obesity. To read more: https://www.dietdoctor.com/the-american-obesity-epidemic-reaches-a-new-record

Obesity and the Brain

Obesity can lead to changes in the brain’s physiology, including insulin and leptin receptor resistance, both of which can actually promote over-eating and inhibit the pathways in the brain associated with appetite suppression. Molecules known as saturated fatty acids can freely cross and accumulate within brain tissue that can lead to the activation of inflammatory pathways within the brain. This inflammation can further contribute to the insulin resistance and inability to utilize insulin for energy.

Figure 2. The control of energy and maintaining homeostasis in the hypothalamus, where leptin and insulin both act directly on neurons in the ARC. Once AgRP neurons are activated, they tell the body to eat, while the POMC neurons tell the body to stop eating (shown on the left). However, if there is insulin and/or leptin resistance, this increases activation of the AgRP neurons and inhibits the POMC neurons, thus indicative of over-eating and an imbalance in energy throughout the body (shown on the right).

Insulin resistance can also lead to inhibition of POMC neurons. These neurons are especially important to the story because they are normally activated after we eat food and tell us to STOP eating. However, inhibition of POMC neurons leads to the overeating associated with obesity. Under normal conditions, when you feel hungry, AgRP neurons are activated and tell us to go ahead and eat food in order to gain energy. There is evidence that the body’s ability to maintain homeostasis is imbalanced as there is an increased ratio of AgRP:POMC neurons in the brain.

Treatment options

While fast food French fries, pizza, donuts, ice cream, and cookies all sound like great snacks to have, it is important to remember to eat these high-fat foods in moderation, especially with finals week and Christmas break approaching right around the corner. Stress eating is real, friends! We can’t get rid of sugar once and for all, but we can start to eat healthier and regularly exercise.

However, sometimes the use of medications in combination with a healthy diet and exercise program may be beneficial. Some common medications prescribed:

- orlistat (Xenical)– this medication belongs to a class of lipase inhibitors. Orlistat works by preventing fat in foods eaten from being absorbed in the intestines.

- lorcaserin (Belviq)– this medication belongs to a class of serotonin receptor agonists. It works by increasing feelings of fullness so that less food is eaten essentially.

- phentermine and topiramate (Qsymia)– Phentermine is in the medication class known as anorectics. It works by decreasing appetite. Topiramate is in a class of medications called anticonvulsants. It works by decreasing appetite and by causing feelings of fullness to last longer after eating.

- liraglutide (Saxenda)– Liraglutide is used with a diet and exercise program to control blood sugar levels in adults with type 2 diabetes (condition in which the body does not use insulin normally and therefore cannot control the amount of sugar in the blood) when other medications did not control levels well enough. It is in the medication class known as incretin mimetics. It works by helping the pancreas to release the right amount of insulin when blood sugar levels are high. Insulin helps move sugar from the blood into other body tissues where it is used for energy. Liraglutide injection also slows the emptying of the stomach and may decrease appetite and cause weight loss.

Now you know a little bit more info on obesity and how constantly consuming a high-fat diet can re-wire and change the physiology of the brain. Obesity is a brain disease. Remember that “everything in moderation” are good words to live by when it comes to eating food.

Read more on BMI and obesity here: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/defining.html

Image 1: https://steamregister.com/obesity-and-your-brain/

Image 3: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/317546.php

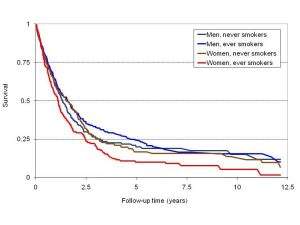

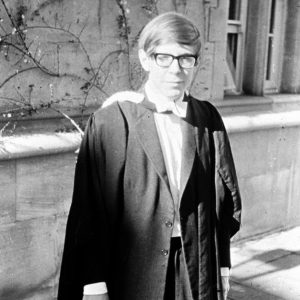

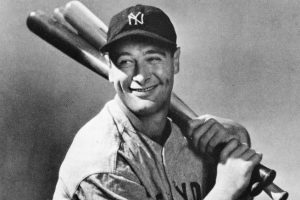

Above are Stephen Hawking and Lou Gehrig, two of the most famous people to have suffered from ALS. There are approximately 30,000 Americans living with ALS in the United States today.

Above are Stephen Hawking and Lou Gehrig, two of the most famous people to have suffered from ALS. There are approximately 30,000 Americans living with ALS in the United States today.

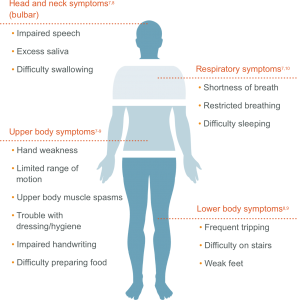

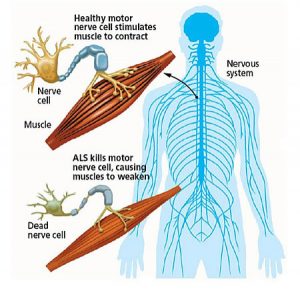

die. As the number of motor neurons decreases, the brain is no longer able to send messages to muscles, which leads to lack of muscle movement. This lack of movement causes muscle strength to weaken and muscle atrophy or muscle waste to occur. While ALS is devastating to the body, the mind of a person suffering from ALS remains sound.

die. As the number of motor neurons decreases, the brain is no longer able to send messages to muscles, which leads to lack of muscle movement. This lack of movement causes muscle strength to weaken and muscle atrophy or muscle waste to occur. While ALS is devastating to the body, the mind of a person suffering from ALS remains sound.

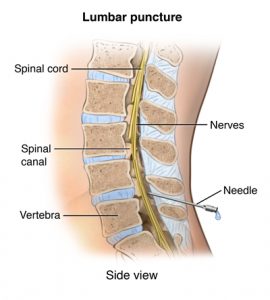

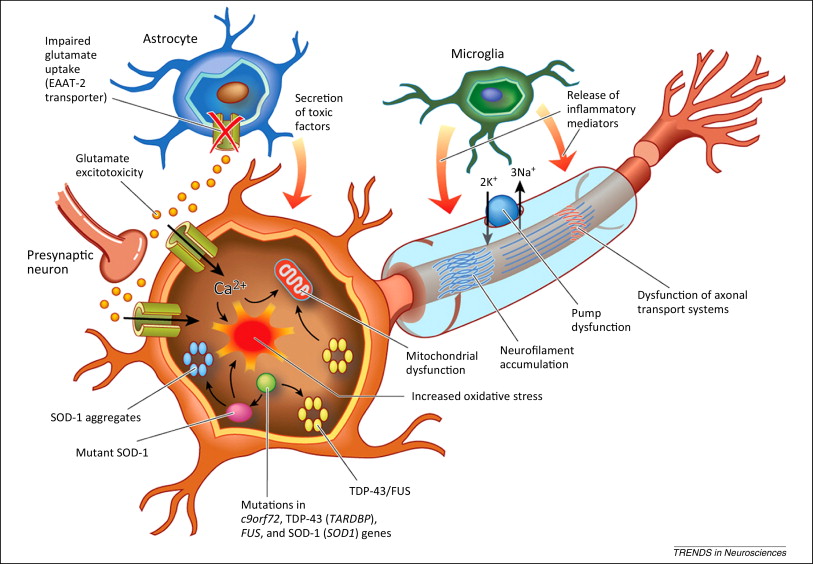

in the brain and spinal cord leading to their eventual death and therefore loss of mobility and eventual paralysis (see picture on the right). Most of the patients end up passing due to respiratory distress or failure because of these neurons.

in the brain and spinal cord leading to their eventual death and therefore loss of mobility and eventual paralysis (see picture on the right). Most of the patients end up passing due to respiratory distress or failure because of these neurons.