The taboo topic of marijuana is splitting America at state lines. While the drug is illegal on a federal level, Individual states are taking opposing stances on its legalization in regards its use, psychoactivity, and possession incrimination.

I would venture to say that the debate of recreational v. medicinal use is actually stigmatizing marijuana research, making it difficult to find funding and fully understand its benefits or risks. While the public is so concerned with WHO should be able to legally utilize marijuana, we must rather educate ourselves on HOW marijuana has so many diverse effects.

How it works

Marijuana is a very complex plant with over 400 chemicals, 15% of which make up the active ingredients that are cannabinoid-based. Cannabidiol, Cannabinol, and THC are the among the most popular cannabinoids in marijuana, as they are responsible for both the psychotropic and medically beneficial effects of the drug.

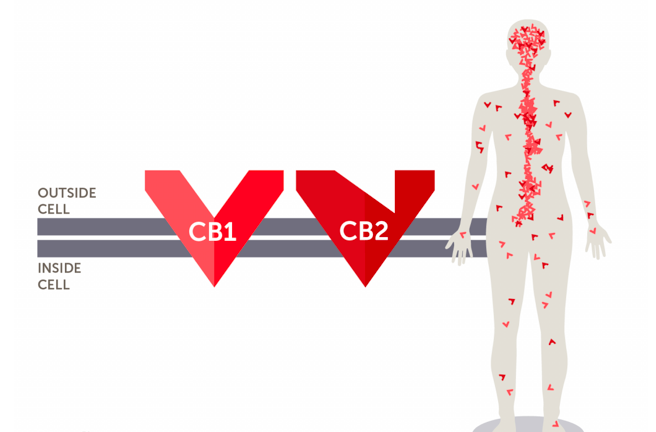

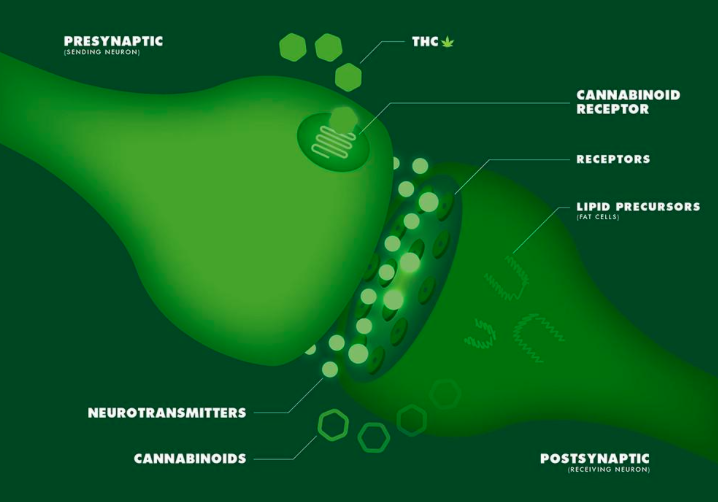

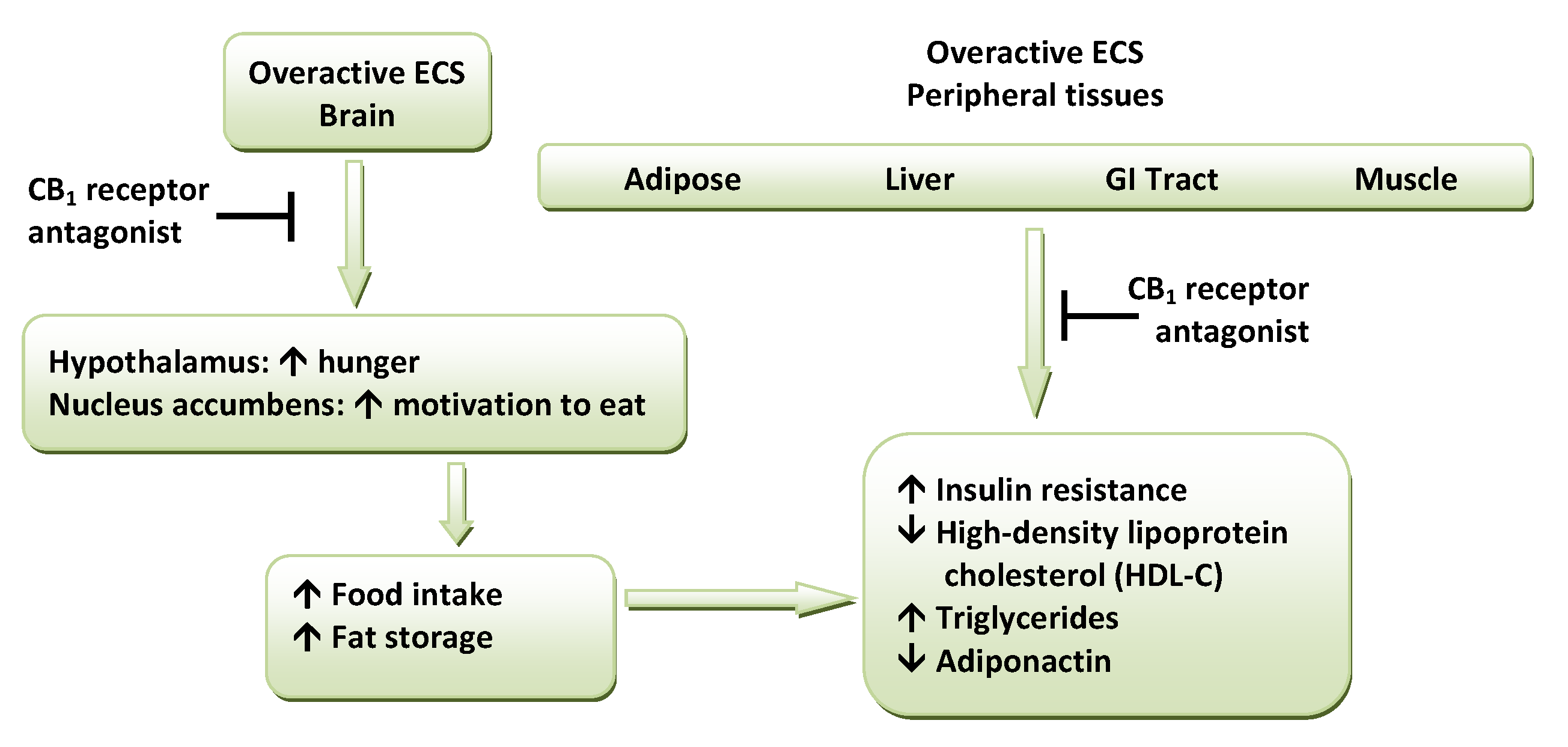

So how does these work in our brain? Well, our brain actually has a system in which we make and use our own cannabinoids, called endocannabinoids (eCB). Two common forms of eCBs are anandamide (AEA) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), which are made and released in the brain.

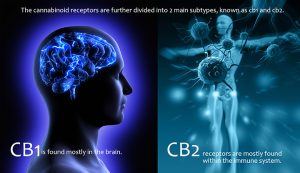

These molecules bind to cannabinoid receptors (cB1 receptors) and can hold a number functions. For example, one function includes its inhibitory effects. When the eCB is released, transports back up to the pre-synaptic neuron, and shuts down the pathway and causes its pain-relieving, or analgesic, effects.

The medicinal benefit of marijuana use

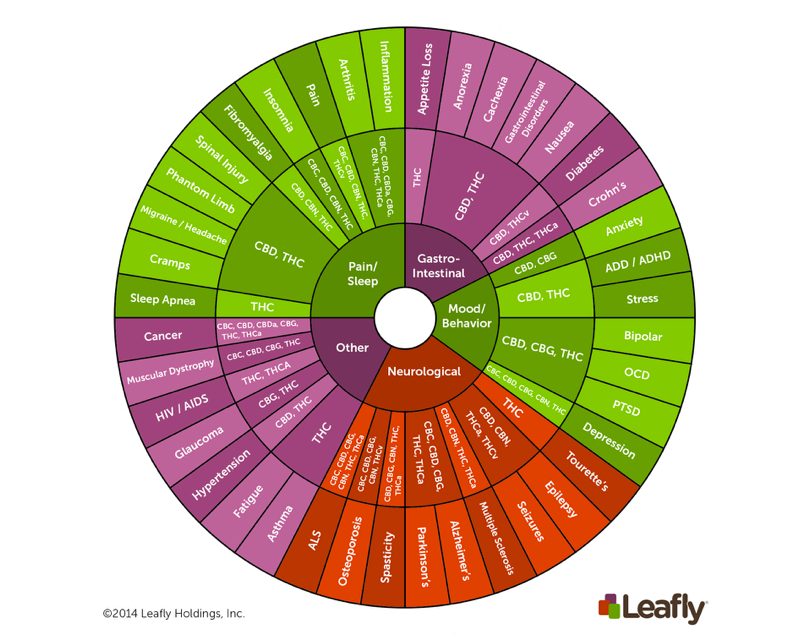

THC and Cannabinol have psychotropic effects that are responsible for the user ‘high,’ but Cannabidiol does not. Not only does it lack the ‘high,’ but it also has many therapeutic benefits found in preclinical trials. These include anti-seisure, anti-inflammatory, anti-psychotic, analgesic, and neuroprotective properties.

If researchers were able to isolate this ingredient, the medical use of the altered marijuana would then run through the same FDA testing for approval as any other legal medication. However, research and funding is needed to get marijuana to this point in the process.

The recreational harm of marijuana use

Marijuana on our streets today is not the same marijuana baby boomers were smoking in the 1970’s. In the 1990’s, marijuana had about 3.1% THC content- marijuana tested in 2014 had 6.1% THC, almost doubling in the past 20 years.

Not only are growers increasing levels of THC content to induce a more effective high, they are developing new ways of administering the drug. They have now created cannabis oil extracts, which are inhaled and contain an astonishing 50-70% THC.

With increasing levels of THC, one must also consider its propensity for addiction. It’s a common sentiment that marijuana is not ‘that’ addictive, which does hold some truth when compared to hard drugs like cocaine and methamphetamine.

30% of marijuana users develop marijuana use disorder, in which they feel dependency and withdrawal symptoms, but subside after 2 weeks of their last use. If withdrawal symptoms continue, it is considered an addiction and develops in 9% of marijuana users. As THC content increases, so does their risk for developing an addiction.

So who should use?

THC and other psychotropic ingredients in marijuana increases its potential for abuse and decreases one’s cognitive judgement. These negative components are not grounds for consideration of legalizing recreational use of marijuana.

However, that it not to say that marijuana doesn’t have a potential benefit to our society. By isolating the beneficial components without the negative side effects, we can be one step closer to legalizing medical marijuana. Being an educated member of society and advocating for continued research on this topic will collectively empower us to improve patient outcomes.