Preconceptions of Addiction

What comes to your mind when you hear the word “addiction?” Maybe you think coffee—how you have to have it every morning to be able to function. Maybe you think of a loved one that has battled alcoholism for years. Or maybe you imagine a creepy old man lurking in a dark alley, wearing a trench coat and offering you a small bag of white powder. Personally, I tend to think of the latter example. The stereotypes associated with addictions, and the way media portrays this illness, tend to lend themselves to these types of images. However, addictions don’t relate only to drugs, and they don’t only affect people with drug history. In fact, I would be willing to bet that every single person on the planet has at least one addiction, though it isn’t necessarily dangerous. Addictions could include social media, food, or television. An addiction can be thought of something you want to stop doing, thinking, or taking, but find it nearly impossible to do so, despite the consequences. Is there something in your life that you think could be an addiction? Keep your “addiction” in mind as you read through the rest of this post. . . Relating an abstract idea to yourself helps you to understand it (or so I have been told).

Addicted to Science

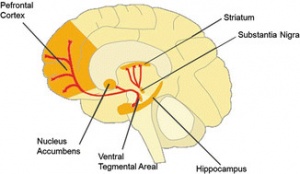

The main brain pathway that has been studied in addiction is the reward pathway, primarily the areas of the ventral tegmentum (VTA) and the nucleus accumbens (NAc). An image of where these areas are located within the brain is shown below.[1]

There are two molecular components of the reward pathway that interact in drug addiction.

cAMP Response Element Binding Protein

cAMP response element binding proteins (CREB) are activated in the NAc during drug addiction. CREB is important in addiction because it contributes to the impaired reward pathway highlighted above. When CREB is activated, it produces a peptide (dynorphin) that suppresses dopamine transmission from the VTA (where dopamine is produced) to the NAc which is the reward center of the brain (reinforces an activity or feeling). I know that summary was really scientific and had a lot of acronyms, so I will do my best to break this down a little more. There is a protein in the brain that is activated in the brain’s reward center when an individual is addicted to something—CREB. This protein produces another protein that stops a neurotransmitter called dopamine from traveling from its production site to its destination. Think of the function of the CREB as placing a “road closed” sign in the brain. The road closed sign (dynorphin) stops the car (dopamine) from getting to its destination (NAc), which causes the driver (you) to be upset (no activation of reward center). This is a really simplistic way of describing the function of CREB, but I think it illustrates the central idea in a more relatable way.

Delta FosB

So, we just discussed the role of CREB in the brain where addiction is concerned, but CREB has a special relationship with another protein called Delta-FosB. This protein is the predominant Fos family protein that is expressed after repetitive drug exposure. The Delta-FosB protein’s function is essentially opposite to that of CREB—FosB increases sensitivity to the addictive stimulus and promotes a natural reward response. I don’t have a driving-related analogy for FosB, but you are welcome to add your own. FosB and CREB have a really important interaction in the brain’s reward pathway. Dynorphin, as I previously discussed, suppresses dopamine transmission from the VTA to the NAc. However, when FosB is present, dynorphin is suppressed. To talk about it in terms of car analogies, FosB temporarily removes the “road closed” sign imposed by CREB.

The Two Frenemies and Their Role in Addiction

In this final section, I will try to sum up what I talked about in the previous sections then relate it to some characteristics of addiction, as well as the development of addiction, itself. CREB, as we previously discussed, puts a roadblock in the brain that prevents dopamine from activating the NAc which is responsible for giving the “high” feeling. Based on this information, drug tolerance (needing more of the drug to receive the same effect) is induced by the activation of CREB. FosB is responsible for temporarily removing this roadblock, thus allowing dopamine to travel to the NAc and trigger a “high.” I hope this illustrates how these two proteins are related to characteristics of addiction, but how do they relate to the development of addiction? Great question. Another characteristic of FosB is that it induces synaptic plasticity. Synaptic plasticity is the strengthening and/or growing connections in a neural pathway. This means that, when FosB is present due to repeated drug use, it is strengthening the pre-existing connections and creating new connections in the reward pathway which results in greater and faster activation of that pathway. Addiction occurs because you have taught your brain how to respond to the presence of a specific stimulus via positive reinforcement.

[1] https://www.researchgate.net/figure/1-The-dopaminergic-mesocorticolimbic-circuit-the-VTA-ventral-striatum-including-the_fig2_270788950