By Cullen Knowles

When people hear the word schizophrenia, Hollywood movies about deranged serial killers and lunatics often come to mind. A recent example is the movie Split, a horror/thriller about a kidnapper with 24 different personalities contained within his mind, driven to do horrible things because of his mental illness (1). There are many other examples like Split in popular culture, in which an individual with schizophrenia is portrayed as being dangerous to other people, and these examples illustrate the stigma surrounding people with schizophrenia and other mental illnesses in our society.

Unfortunately, this perception of people suffering from Schizophrenia is really founded on a series of misunderstandings about the disorder, rather than scientific evidence. Most people think of schizophrenia as a disease in which a person’s mind contains multiple personalities, some benign and others malicious. This misperception likely arises from the word schizophrenia itself, which directly translates into ‘split mind.’ In reality, people who suffer from this disease do not have ‘multiple personalities’ inside their minds, but have a variety of symptoms categorized as either positive or negative.

Positive symptoms include hallucinations (primarily auditory hallucinations), disorganized speech or thought patterns, and inappropriate emotional responses, such as laughing during a funeral or crying during a comedy movie (2). Negative symptoms are characterized by the absence of emotion, or a lack of appropriate emotion, such as toneless voices, expressionless faces, and rigid bodies (2). Individuals who suffer from schizophrenia may either exhibit positive or negative symptoms, or a mixture of both, but at least three of these symptoms must be present in order to be diagnosed with the disorder. No ‘alternative personalities’ are present within the mind of someone who suffers from schizophrenia.

The physiological causes of these symptoms, and schizophrenia in general, are largely unknown, especially to the general public. Brain abnormalities, such as the smaller size of several regions of the brain, have been implicated with the onset of the disorder, and environmental factors such as stress are thought to be risk factors as well. The hippocampus of the brain, which is responsible for the coordination of memory formation, is one of the key areas affected by schizophrenia. Decreased neuronal connectivity and plasticity in the hippocampus is associated with schizophrenia, and this could explain the racing thoughts and memory problems that occur in patients with the disease (3). The disruption of signaling pathways responsible for the growth and differentiation of neurons in human embryos is also thought to play a role in the development of schizophrenia.

Understanding the real symptoms of schizophrenia, and understanding some of the science behind how the disorder develops, is crucial to understanding why people with schizophrenia behave the way they do. Without an understanding of what schizophrenia is, it’s impossible to overcome society’s misperceptions of schizophrenia and treat people suffering from the disorder with compassion.

Sources:

1. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Split_(2016_American_film)

2. http://schizophrenia.com/diag.php#

3.https://moodle.cord.edu/pluginfile.php/625277/mod_resource/content/2/2013%20wnt%20GSK%20and%20schizophrenia.pdf

Image: https://img.webmd.com/dtmcms/live/webmd/consumer_assets/site_images/articles/health_tools/schizophrenia_overview_slideshow/webmd_rf_photo_of_mri_brain_scans.jp

What’s Wrong With the Current Medication for Schizophrenia?

What Is Schizophrenia?

Schizophrenia is a psychotic disorder in which affected patients experience a wide range of symptoms, categorized into positive or negative symptoms and cognitive defects (Figure 1).

Although there is much more to be known about schizophrenia, it is believed that one of the causes of the disease is an interference in the development of neurons. This points to Wnt signaling as an important factor. The D2 receptor for dopamine is over activated, which will in turn inhibit Akt, a phosphokinase. This will cause excessive activation of GSK, resulting in a lack of β-catenin, so TCF/LEF transcription (gene transcription important in cell growth and differentiation) will be inhibited.

Effects of Antipsychotic Drugs

Antipsychotic drugs are used to treat patients who are suffering from some type of psychosis. Psychosis is a condition affecting the mind and involves a loss of contact with reality, such as delusions or hallucinations. The general mechanism of antipsychotics is D2 receptor antagonism. These drugs work to reduce the positive and/or negative symptoms (see Figure 1) of schizophrenia, but do not work to cure the disease itself.

One key to effectively treating schizophrenia is finding the right balance between medications (as many patients are also taking anti-depressants and/or anti-anxiety drugs) and possibly also including some type of psychotherapy, such as cognitive therapy, group therapy, or social skills training.

There are two types of antipsychotics: typical (first-generation) and atypical (second-generation). Atypical drugs were introduced due to many of the typical drugs cause debilitating extrapyramidal side effects, such as tardive dyskinesia (TD), parkinsonism, akathisia, and acute dystonias.

As is expected from a drug working to soothe neural problems, the list of side effects given by the FDA is quite long. This list includes:

- Drowsiness

- Dizziness

- Restlessness

- Weight gain

- Dry mouth

- Constipation

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Blurred vision

- Low blood pressure

- Uncontrollable movements (ex. ticks and tremors)

- Seizures

- Low white blood cell count

- Muscle rigidity

- Persistent muscle spasms

Long-term use of antipsychotics can also result in many serious side effects, one of them being tardive dyskinesia. TD can range from mild to severe, and causes uncontrollable muscle movements, typically around the mouth. TD can be incurable, but some patients can have partial to full recovery after discontinuing their antipsychotic medication.

The Problem With Anti-Psychotic Drug Treatments

Many patients stop taking their anti-psychotic medication after only a short period of time due to these numerous and, in many cases, quite severe side effects. Another drawback to the current medications for schizophrenia is that these drugs do not work on curing the disease. This means that a person suffering from schizophrenia must weigh the many side effects against not a cure for their ailment, but only the hope of attempting to return to a ‘normal’ life.

Due to the many factors that can cause schizophrenia and the limited knowledge of the mechanisms of this disease, it is going to be difficult to move forward in the treatment of schizophrenia, but difficult does not mean impossible.

Can Your Doctor Test You for Schizophrenia?

Would you want to know if you have schizophrenia?

Schizophrenia is a neuropsychiatric disorder that affects about 1% of the general population as well as their family and friends.

Schizophrenia has many symptoms:

- Depression

- Withdrawal from friends and family.

- Lack of motivation

- Disorganization: this is more of an extreme disorganization, such as disorganization of words while speaking.

- Delusions: believing things are real when they are not.

- Hallucinations: visual or auditory stimulus that don’t exist. To a patient with Schizophrenia, it is real.

- Catatonia: being fixed in one place for a very long time

A Glimpse Into Schizophrenia

Dear King Phillip Came Over For Good Soup. This is a common mnemonic for memorizing the order of taxonomy: Domain, Kingdom, Phylum, Class, Order, Family, Genus, Species. It is also just one of the many examples of how we put things into boxes to try to organize the chaos that surrounds us.

We like it when things are black and white, with very minimal gray area. But what happens when we can’t contain something inside its box? This seems to be an issue when it comes to mental illness, i.e. how we define certain disorders and how do they differ from one another, etc. Mental illness is a rather broad topic, spanning across countless disorders and so I would like to shed some light on one in particular: schizophrenia.

What is Schizophrenia?

Schizophrenia is considered to be a mental illness as mentioned previously, however it is also a neurological developmental disorder. Meaning that it begins sometime during our development, often during childhood.

What Causes It?

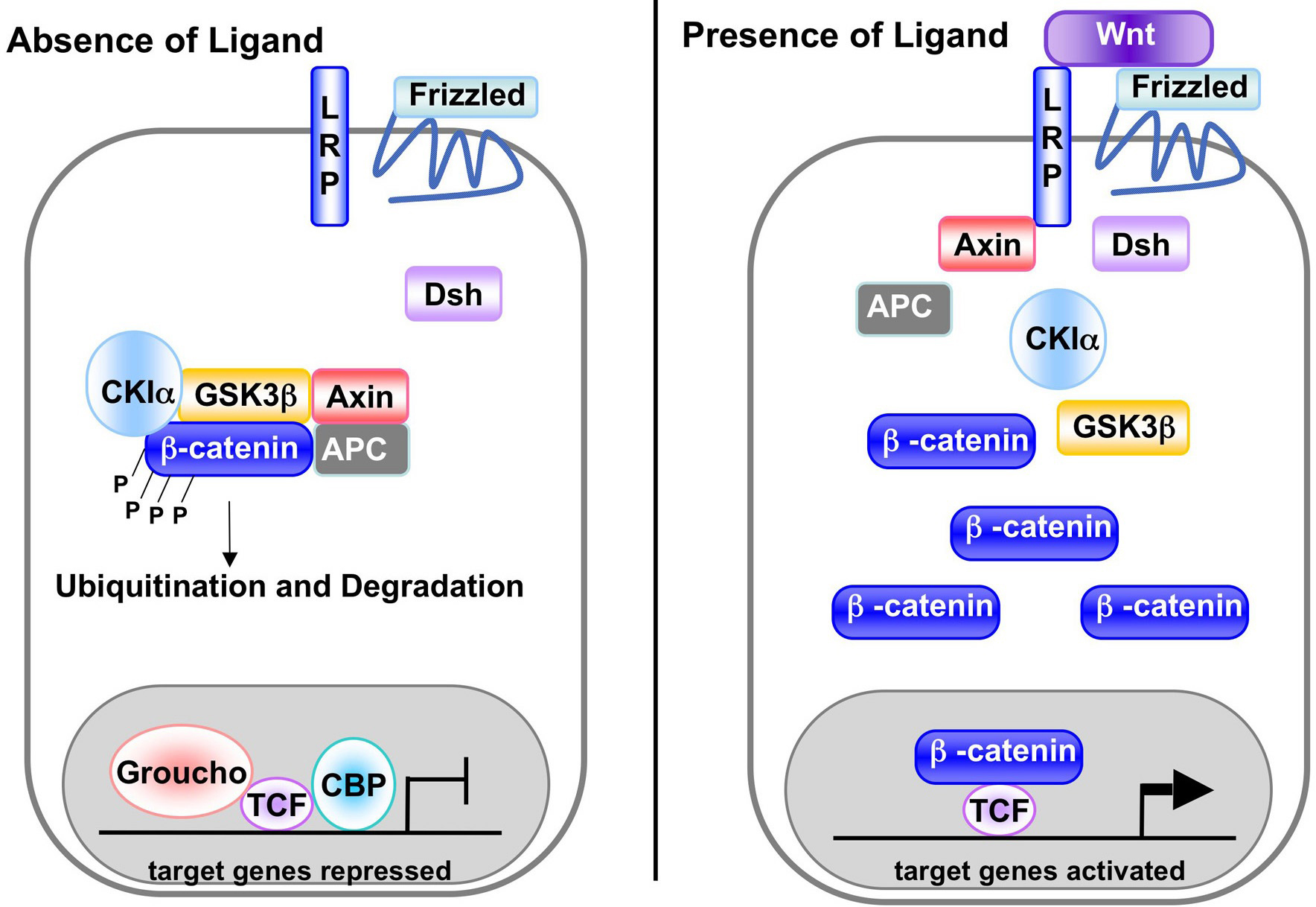

The cause of Schizophrenia is not exactly known and it appears that multiple factors can come into play, such as environment and genetics. That being said, there is one pathway in the brain that may be a key player in this disorder, known as the Wnt signaling pathway. The Wnt pathway consists of three different “routes” so to speak. The one implicated in schizophrenia involves an important protein known as β-catenin. When the pathway is shut off, β-catenin is trapped in a destruction complex, which is just structure made up of many other proteins (GSK3β, Axin, Apc, and CK1a). This leads to an inhibition of transcription factors, which means that some genes are not expressed.

For more info on this pathway check out this video! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oweNT288BXo

What Does β-catenin Have To Do With Schizophrenia?

Individuals with schizophrenia tend to have an increase in GSK3β activation, which results in β-catenin being trapped in the destruction complex and is unable to express certain genes. This is caused by an over-activation of D2 receptors in the brain due to the release of dopamine (DA). When these receptors are activated, they shut off a protein known as AKT. AKT’s job is to keep GSK3β in check, but if it’s turned off then GSK3β is over-activated and β-catenin remains trapped.

Now that I have given a little background on schizophrenia, I would like to go back to the idea that need everything needs a “box”. Symptoms of schizophrenia often overlap with other disorders such as bipolar disorder and schizoaffective disorder. Also, people express symptoms in different ways and at various degrees, creating a kind of spectrum. This causes a lot of gray areas and so often times people are misdiagnosed. This is true for many other mental illnesses as well and so it begs the question of can we really be so cut and dry when diagnosing or do we need to allow for some fluidity? Do we need to spend more time helping people with their symptoms and less on putting them in a box?

Featured Photo Credit: Abhijit Bhaduri (flickr.com)

Let’s Consider the Questions

Did You Know…

43.8 million Americans experience mental illness each year. And of those, about half a million Americans suffer from Schizophrenia each year, which makes this a very common disease. Keep in mind, this disease affects a lot of people we may encounter in our everyday lives.

https://www.nami.org/

What is Schizophrenia?

Schizophrenia is a considerably common mental illness that involves positive symptoms (hallucinations, paranoia, compulsive behavior, etc.) and negative symptoms (absent emotional responses, social withdrawal, reductions in speech, etc.) and can greatly affect everyday life for those with the illness.

What Causes Schizophrenia?

In our brains, we have many different complex biological pathways that lead to a specific response. The main pathway that is disrupted in Schizophrenia is the Wnt/GSK3 Pathway.

The most important molecule in this pathway is a protein, beta-catenin. This protein is needed for normal gene expression.

However, in people with Schizophrenia, an increase in dopamine in the brain over stimulates D2 receptors (dopamine-specific receptors). The activation of this new pathway inhibits another key molecule, Akt, which in turn cannot inhibit GSK3.

Therefore, GSK3 in the Wnt Pathway is now active and is a part of a destruction complex that destabilizes beta-catenin. Beta-catenin is now no longer able to provide necessary gene transcription for the brain.

The under-expression of genes in the brain and anywhere in the body is detrimental to normal function. Therefore, the result of this failed pathway leads to Schizophrenia.

https://moodle.cord.edu/pluginfile.php/625277/mod_resource/content/2/2013%20wnt%20GSK%20and%20schizophrenia.pdf

www.wormbook.org

How do we fix Schizophrenia?

There is more to Schizophrenia than we know biologically. The disease is a combination of internal and external factors. Drugs on the market mainly target D2 receptors which is not solving the problem just covering it. But therapy can help keep patients on medications necessary for remission.

https://moodle.cord.edu/pluginfile.php/625277/mod_resource/content/2/2013%20wnt%20GSK%20and%20schizophrenia.pdf

How Would You Feel About Your Doctor Having Schizophrenia?

Understanding the prevalence, symptoms, underlying causes, and possible treatments of Schizophrenia, here are my final thoughts and questions:

It is highly likely one of our doctors suffers from some type of mental illness, maybe even Schizophrenia. Should doctors be required to go through mental illness tests?

Knowing there are drugs on the market to subside symptoms, do you think your doctor should be able to practice medicine if he/she has Schizophrenia?

Can doctors without mental illness make the same mistakes as those with mental

illness?

Do we all have some type of mental abnormality whether or not we consider it a mental illness because we all differ in thought and mind?

How does our society treat people with mental illness and should they be allowed to do what they love?

I don’t have all or any of the answers but they are important to consider and ponder.

I know if it were me, I would do everything I could to keep my medical license because it is what I was meant to be, but there are always two sides to the story.

Into the Brain of Schizophrenia

One day, I arrived at work and saw a patient pointing up into space talking about the lights that he could see dancing around and the voices he heard talking to him coming from the lights. I was immediately taken aback by this man as this is not a usual occurrence. Even as I was working in an inpatient psychiatric treatment facility, rarely would anyone be this visibly confused and disoriented to this extent. Later, I found out that this man had schizophrenia. When his parents arrived at the hospital to see him I had the opportunity to speak with them as they told me he usually has a relapse like this at least once a year, “it’s just part of the season.”

Although, I saw this patient with schizophrenia, I had never thought about the implications in the brain. It had never occurred to me to wonder about how this man had become so mentally distraught. In an article from clinical genetics, they discuss how the Wnt signaling pathway is implicated in schizophrenia. This pathway, when activated, is responsible for turning on certain transcription factors that usually promote cell growth. Therefore, this pathway is highly active during embryological development. The article discusses how the Wnt pathway is shut down or does not run as smoothly in patients with schizophrenia. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) is an important molecule in the Wnt pathway as it binds to ß-catenin. When GSK3 is bound to ß-catenin, it keeps ß-catenin from going to the nucleus and eliciting transcription for cell growth. Normally, when Wnt is present it binds to a frizzled receptor on the cell membrane and causes ß-catenin to go to the nucleus and begin transcription.

Although this pathway seems to contribute to schizophrenia, there are so many other factors involved in the disease. Environmental stressors like abuse are also known to cause schizophrenia along with other genetic markers like at risk genes which can be passed down from generation to generation. The total process behind the cause of schizophrenia is not yet known. We do know that it impacts the brain and changes it in such a way that cannot be fully understood. The treatments that are in place now are not always effective and can have very debilitating side effects like tardive dyskinesia that can impact a patient for their whole life. Like my patient in the hospital, psychotic breaks are often a part of having the disease and non-compliance when taking the medications is a huge issue. I hope that one day we will be able to determine a better option for those suffering from this disease. However, at this point I think it is best to keep an open mind about those suffering from mental illness. We cannot truly understand the struggle they are going through, and often there is not any good options for them. I know that my patient recovered to a normal state and was able to leave the hospital, however, I hope one day, hospitalization is not part of his yearly routine.

For access to this article and more information about the wnt pathway go to:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23379509

Featured image from:

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/body/brain-transplants.html

The Beautiful Mind of Schizophrenia

A Beautiful Mind tells the story of a mathematician, John Nash, and his journey with schizophrenia. This movie gives a Hollywood look into the devastating effects this mental illness had on John’s life. However, scientifically what does this beautiful mind look like? Researchers are still trying to pin point the cause of schizophrenia, however, they have determined an important signaling pathway in the pathology of this mental illness, the Wnt and GSK3 signaling pathway.

The Wnt and GSK3 signaling pathway plays an important role in schizophrenia. A destruction complex exists in the cytosol (the cell’s fluid), which is composed of b-catenin, GSK3b, Axin, CK1a and APC. This destruction complex is basically like a tower for b-catenin, holding it hostage in and eventually destroying it (deactivating it with a proteasome). In the nucleus, there are transcription factors that are only activated with b-catenin, so when the destruction complex is present, specific genes are not being transcribed and ultimately not being expressed. In order to destroy the destruction complex a signaling molecule called Wnt must bind to a receptor (frizzled) on the cell’s membrane. After Wnt binds, a protein on the inside of the membrane named Disheveled (DVL) is activated. Wnt and ultimately DVL are b-catenin’s knight in shining armor, freeing it from its tower by dissociating the destruction complex, and allowing b-catenin to safely continue its journey to the nucleus. In the nucleus, b-catenin binds to transcription factors TCF and LEF which then activates the transcription of specific genes, such as Cyclin D1.

This story of a damsel in distress (b-catenin) and a knight in shining armor (Wnt) plays an important role in the beautiful mind of schizophrenia. In the brain of someone with this mental illness, D2 receptors (dopamine receptors) inhibit an enzyme called Akt. This enzyme usually inhibits GSKb, thus allowing the destruction of the destruction complex. However, when Akt is inhibited it allows GSKb to build higher walls to the tower enabling the imprisonment/ destruction of b-catenin. Therefore, this pathway’s dysregulation leads to specific genes being suppressed instead of expressed.

One way that this schizophrenia is being treated is by targeting and inhibiting D2 receptors. Therefore, Akt is not inhibited and can do its job of inhibiting GSKb, which allows for b-catenin to travel to the nucleus. Antipsychotic drugs are what is used clinically today to do this. Although this may seem happy ending with the management of schizophrenia, there is a long way to go with regards to an effective and sustainable treatment.

Antipsychotic drugs are the drug of choice when it comes to schizophrenia. However, this all depends on the point of view. For physicians, antipsychotics seems like the handsome prince who is here to save the day and to help combat the symptoms an individual faces. For many patients, these drugs alleviate the positive symptoms of schizophrenia but they come at an ugly cost. Patients may feel like Fiona did when her handsome prince turned out to be Shrek, disappointed. Many antipsychotics come with nasty side effects that can cast a shadow on the positive things the drug is doing.

Now that researchers are starting to uncover the mechanisms and pathways behind schizophrenia, hopefully this will eventually lead to the discovery of a beautiful treatment plan or drug that will end in a happily ever for patients.

For more information of the Wnt and GSK3 signaling pathway in Schizophrenia please visit:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23379509

Feature photo from: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/318454.php

Why My Capstone Experience Was Worthwhile

Coming in to Concordia four years ago, I had been told many times and was aware of how great of a school it was. I knew I would come out of my undergrad with a good education, but I had no idea what I was getting myself into and the amount of work (and tears) it would take. I’ve had the entire day after graduation to reflect on my experiences, and I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about my “capstone” course, neurochemistry.

Every student must fulfill their capstone requirement by the time they graduate. The purpose is to partake in a course or an internship that challenges you to learn new material while connecting with everything else you’ve studied prior. There are specific outlined goals for the capstone to accomplish this, and I think it would be a good idea to run through them before continuing:

- Instill a love for learning

- Develop foundational skills and transferable intellectual capacities

- Develop an understanding of disciplinary, interdisciplinary and intercultural perspectives and their connections

- Cultivate an examined cultural, ethical, physical, and spiritual self-understanding

- Encourage responsible participation in the world.

Neurochemistry was not necessarily an easy course for me. The chemical pathways did not make sense right away, the papers were long and filled with terms and abbreviations I had never seen before, and I am not typically the most outspoken student in any classroom. However, I would not consider it as the hardest course I have taken at Concordia, either, as I had expected it to be. Especially by the time I had adjusted to the setup of the course, it did not quite meet the expectations I had for the infamous capstone experience.

The first couple of weeks were designated for gaining a basic understanding of cellular signaling and basic neurochemical pathways. This was honestly the most difficult part of the course for me, due to the fact that I had never taken any neuro courses before, and a lot of the concepts were fairly new to me. Once we got down some of the basics, we moved on to focusing on a single topic each week. Topics ranged from eating disorders to concussions to neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s disease. Prior to meeting on Monday, we were assigned to read the assigned article and come prepared with a summary and questions. After discussing our initial thoughts on Monday, we would each choose a subtopic to research that was either confusing or was something we wanted to know more about. On Wednesday, we would share our findings with each other one-on-one in a “speed-dating” fashion. Friday’s were dedicated for discussion on what we had learned and how the issue affects our society, and we would start the whole process over for another topic the next week.

While this setup did not challenge me as much as I was expecting, I feel the course more than fulfilled the outlined requirements I listed earlier for a capstone.

The most unique thing about neurochemistry is that we did not just learn about the neurochemistry of whatever disease we were focusing on. We would challenge each other to think about other issues related (directly or indirectly) to the topic. This gave new perspectives on the topic that made me eager to learn more like no other class has done before. I also simply just noticed myself wanting to learn more about mental health and related disorders as the semester progressed. Not that I had much free time to spare, but I would choose to look up and research something over my actual homework and studying (oops). I was also challenged to express my thoughts and contribute to class discussion daily. My communication skills, as well as my self-confidence, drastically improved, allowing me to share my knowledge with others more effectively. I was challenged to think outside of my comfort zone, prompting self-reflection on how I was interpreting the presented information and how it could be interpreted differently. Our final project, a seminar on eating disorders among college student athletes, gave me the opportunity to reach out to the public to raise awareness on an issue affecting our campus. The goal was to take our knowledge and share it in a way that a general audience would be able to understand. Our communication skills and our creative thought processes were deeply challenged and cultivated in that experience, but we were able to start a conversation among our community that we hope to keep alive.

I could go on forever about the ways neurochemistry has impacted me. Listed above are just a few important examples illustrating the invaluable experiences I gained. I learned so much about the neurochemistry driving certain disorders and diseases, but I learned even more about myself and how to think outside of my comfort zone. So I will say it again – my senior capstone course was not my most difficult course by any means, but that doesn’t mean I didn’t gain anything valuable from the experience.

Let’s Talk About Parkinson’s

I’m sure you’ve heard about Parkinson’s Disease, but do you actually know what it is or the implications behind it? If you’re like me before I took neurochemistry, the answer is probably no. The only thing I really knew about it was the associated hand tremors.

Parkinson’s disease is a progressive disorder that eats away at the nervous system, affecting movement and cognition. Researchers suspect that the accumulation of a certain protein in the brain may be what’s causing the disease. A deep midbrain region called the substantia nigra plays a role in our controlled movements. In people who suffer from Parkinson’s disease, clumps of aggregated proteins have been found here, leading to the idea that these clumps are interfering with the substantia nigra’s ability to function properly.

The specific alleged proteins are called alpha-synuclein. When produced, they are supposed to fold into a certain shape in order to do what they are supposed to do. However, if they are not made correctly and are misfolded, they will stick and clump together, forming plaques called Lewy Bodies. As this is occurring in the substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease, these plaques are thought to be the culprit for loss of motor control and cognitive function.

Like many other diseases, there aren’t a whole lot of options when it comes to treatments. With complex diseases, it is difficult to find exactly what the source is and how to target it. There are likely many causes! One treatment for Parkinson’s disease, called L-Dopa, is showing positive results. This is basically putting extra dopamine into your brain, which seems to improve control of movements. Symptoms such as hand tremors and rigid movements are therefore reduced in patients. However, after prolonged use, the effects appear to wear off and the drug is no longer helpful.

So my main question is this: why aren’t we talking about Parkinson’s disease? A large percentage of our class had very limited knowledge on the disease, clearly proving that we are not being told anything or partaking in any conversations. As we are about to head into and affect change in the “adult” world, it’s not a good sign for future discoveries if we don’t know anything about the disease were trying to treat.

Apparently for the generation before us, Michael J. Fox has worked diligently as an advocate for research. Fox was an actor, commonly known for playing Marty McFly in the Back to the Future movies from the late 80s. He was also diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease in 1991 and was forced by the symptoms to retire in 2000. He has since been spreading awareness of the disease to attract more donations to fund research. This is great and all… but I think my generation has not been receiving the message. Someone closer to our age needs to step up and take on a similar role that can connect with the millennials. Too soon, we’ll be the ones in charge of making decisions when it comes to funding and research. If we want to make advances in treating Parkinson’s, we need to increase general awareness and instill a passion to eradicate it.

Concordia’s Cap

Neurochemistry certainly blew my mind about the mind. I never knew much about how the brain works, but this class helped to fill in some of the mysterious blanks as to how seemingly abstract processes take place. Let’s view the Neurochemistry class in light of Concordia’s five goals for liberal learning:

Instill a love for learning: I don’t think that this class by itself would instill a love for learning. What is beautiful about Concordia though, is that most of my classes had some topic overlap—even when the classes are across departments. The overall experience of seeing how so many things are connected makes me more excited about learning. I also had Religion and the Body this semester, and many topics dealing with health and positivity overlapped with what we were learning in Neurochemistry.

Develop foundational skills and transferable intellectual capacities: I think that our efforts in reading scientific articles in Neurochemistry will develop into a transferable skill. I will be going to five years of graduate school after this, and probably spend a career in academia afterwards. Being able to read and understand research by other scientists is invaluable and necessary.

Develop an understanding of disciplinary, interdisciplinary and intercultural perspectives and their connections: As I mentioned before, I now know so much more about how the brain works than I did before. In my religion class, I realized how neurochemistry can connect overall health and spirituality. In both of these classes, we made a point of trying to take our newfound understanding in the view of other cultures; for example we consider worldwide diagnosis of some diseases, but we try to remember that not all people will have the same access to doctors.

Cultivate an examined cultural, ethical, physical and spiritual self-understanding: I don’t know that Neurochemistry has cultivated ALL of those things, but it has made me a more understanding person. There is family history of some of the diseases that we’ve talked about, and being able to understand why they occur can really help with blame and treatment of those individuals. It’s been fun getting to explain the science to my grandmother—she likes developing more of an understanding as well.

Encourage responsible participation in the world: I think that the understanding that I’ve gained about different diseases will help me to be a more empathetic person. It isn’t ever really a person’s fault that they have a disease, and when there is no cure that person’s mind set must be much different from mine. During our Friday discussions, I would normally try to figure out how I would feel if I had the disease, or if someone I love had it. I think this kind of empathy is conducive to a more responsible engagement with the world.

I don’t think any one class at Concordia can really fulfil all five of these goals at once—I know that’s kind of the point of a Capstone course, but I just don’t think that that’s realistic. These goals certainly can be reached after four years of a liberal arts experience at Concordia though!