Mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), commonly known as a concussion, is one of the most frequent brain injuries, affecting millions of people each year. It often results from falls, sports injuries, or accidents, and symptoms may include headaches, dizziness, and trouble concentrating. Most individuals recover quickly within days or weeks, and medical professionals often reassure patients that symptoms will fade over time. [2]

But for some, recovery is not so simple. A significant number of people experience lingering effects, such as chronic headaches, memory problems, and emotional difficulties that can last for months or even years. The unpredictability of recovery makes it challenging for doctors to provide clear treatment plans, and factors like genetics, previous injuries, and individual health conditions can influence outcomes. This uncertainty can lead to frustration for both patients and healthcare providers.

Therefore, researchers are working to better understand why some people recover quickly while others struggle with long-term symptoms. By studying brain function, inflammation, and genetic factors, scientists aim to develop better treatments and personalized care strategies. Improving early diagnosis and management of mTBI could help reduce long-term complications and provide clearer recovery paths for those affected.

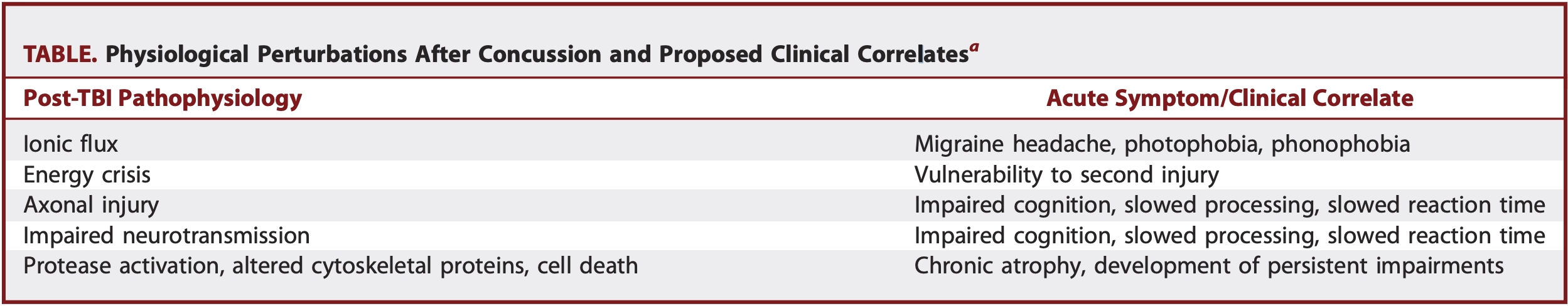

Figure 1[1]

The Role of Genetic Variants in mTBI Recovery

Mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) affects millions of people, with most recovering within weeks. However, some individuals experience prolonged symptoms, and recent research suggests that genetic mutations may play a key role in this variability. Specific mutations in genes related to neuronal repair, inflammation regulation, and metabolic function can influence how the brain responds to injury. For instance, variations in the Apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene, particularly the APOE4 allele, have been linked to an increased risk of cognitive decline after repeated head injuries.[1]

Why Some Heal Faster Than Others

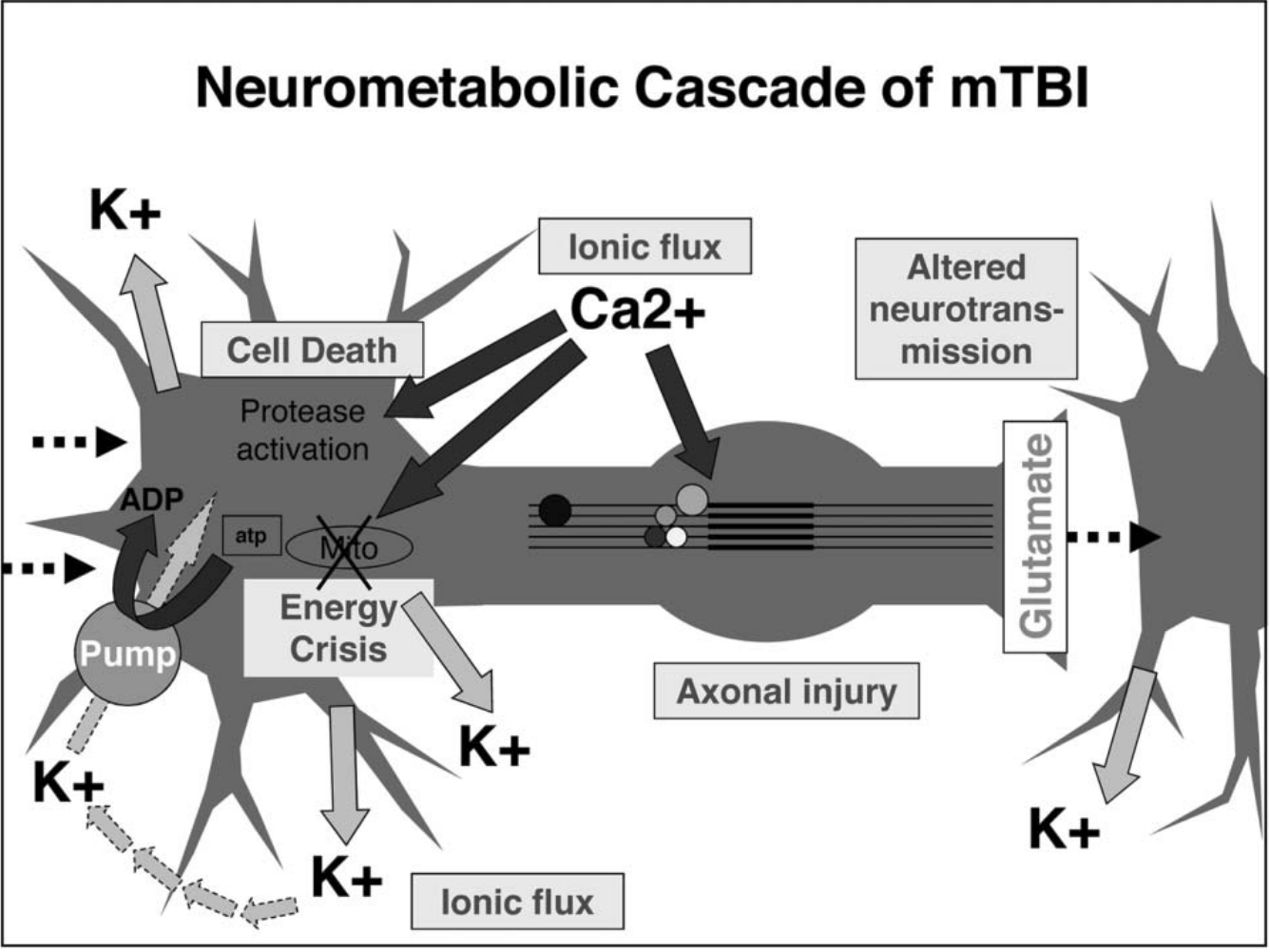

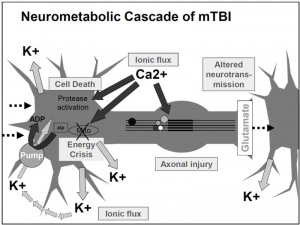

Certain genetic mutations may also heighten susceptibility to concussive trauma. For example, mutations in CACNA1A, a gene associated with ion channel function and migraine disorders, have been linked to an exaggerated response to brain injuries. These genetic factors affect everything from the brain’s initial metabolic crisis to long-term neurodegeneration. Understanding these mutations could help identify individuals at higher risk for severe or prolonged mTBI symptoms, leading to personalized concussion management and targeted recovery strategies.[3]

What role does this play?

The CACNA1A gene plays a key role in ion channel function, which affects neuronal excitability and communication.

- The CACNA1A gene provides instructions for making calcium ion channels in neurons, which regulate brain signaling.

- People with CACNA1A mutations may experience more severe responses to mild TBI, including increased swelling and cognitive issues.

- This suggests that ion channel disorders could impact how the brain reacts to trauma, leading to worse long-term outcomes for some individuals.

The Future of Concussion Care: A Personalized Approach

Understanding the genetic basis of concussions doesn’t just impact athletes or military personnel—it has far-reaching implications for public health, workplace safety, and even everyday activities. If genetic testing could identify individuals more vulnerable to long-term brain damage, it could transform how we approach contact sports, car accident recovery, and workplace safety regulations. Imagine a future where concussion protocols are tailored to an individual’s genetic profile, reducing unnecessary risks and improving recovery outcomes. Should genetic screening become a standard part of concussion management? How might this knowledge shape policies in professional sports or even school athletics?

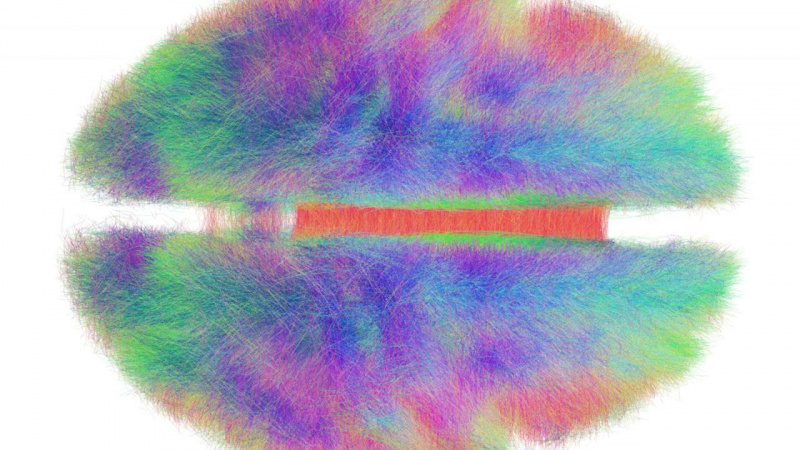

Figure 2[2]

Genetics may hold the missing piece in understanding concussions, and unlocking this knowledge could lead to breakthroughs in personalized medicine and brain injury prevention. As research progresses, the opportunity to protect those at risk grows stronger. Stay informed, advocate for better concussion awareness, and keep the conversation going—because the brain you protect today could shape your future.

Footnotes

[1] Bennett ER, Reuter-Rice K, Laskowitz DT. Genetic Influences in Traumatic Brain Injury. In: Laskowitz D, Grant G, editors. Translational Research in Traumatic Brain Injury. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press/Taylor and Francis Group; 2016. Chapter 9. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK326717/

[2] Brain Treatment Center Newport Beach. (2024, September 16). Traumatic Brain Injury Treatment – Brain Treatment Center Newport Beach. https://www.braintreatmentnewportbeach.com/traumatic-brain-injury-tbi/

[3] McDevitt, J., & Krynetskiy, E. (2017). Genetic findings in sport-related concussions: potential for individualized medicine?. Concussion (London, England), 2(1), CNC26. https://doi.org/10.2217/cnc-2016-0020

[4] Conger, K. (2024, February 16). Concussion: Could your genes increase your risk? Scope. https://scopeblog.stanford.edu/2020/11/30/concussion-could-your-genes-increase-your-risk/

Figure 1

Figure 1 Figure 2

Figure 2

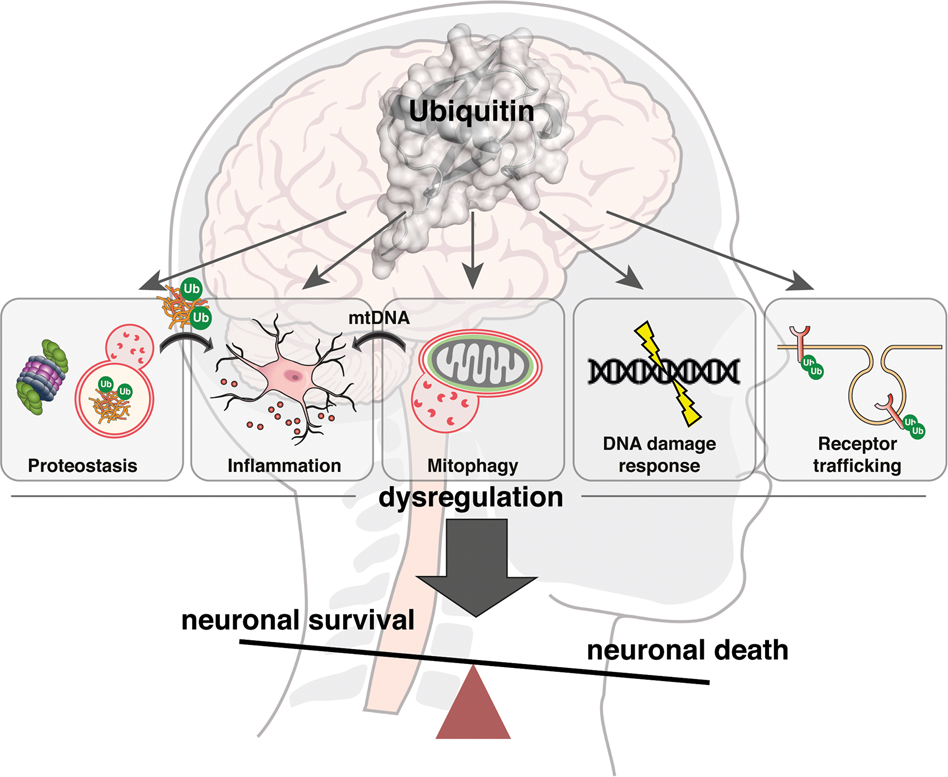

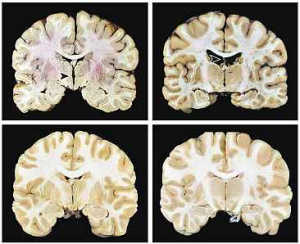

Figure 3

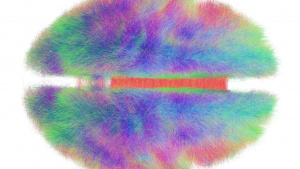

Figure 3 Figure 4

Figure 4 Figure 5

Figure 5